Hamish McRae: How can we get back on the long road to growth?

Economic View: In the case of Japan, economic stagnation was probably inevitable. In the case of the US and UK, it isn't

It is always difficult to distinguish the cyclical from the structural. The preoccupation now and next week is about slow growth in the UK economy at the moment and we will have to see to what extent the Government feels itself able to respond to these concerns. However, much depends on whether this is principally a cyclical problem – that we are finding it very hard to recover the ground lost as a result of the recession – or whether there are deep-rooted structural reasons why the UK is likely to grow more slowly in the future than it has in the past. And that leads to the even wider question: is the West as a whole likely to grow more slowly? Have we all caught the Japanese disease?

There is one immediate point to be made which is that Japanese demography has become particularly unfavourable to growth. The combination of very low birth rates, long life expectancy and minimal inward migration has made it the oldest society on Earth. Some other European countries have a similar pattern, notably Italy, but the US and to a lesser extent the UK hold the prospect of continuing population growth.

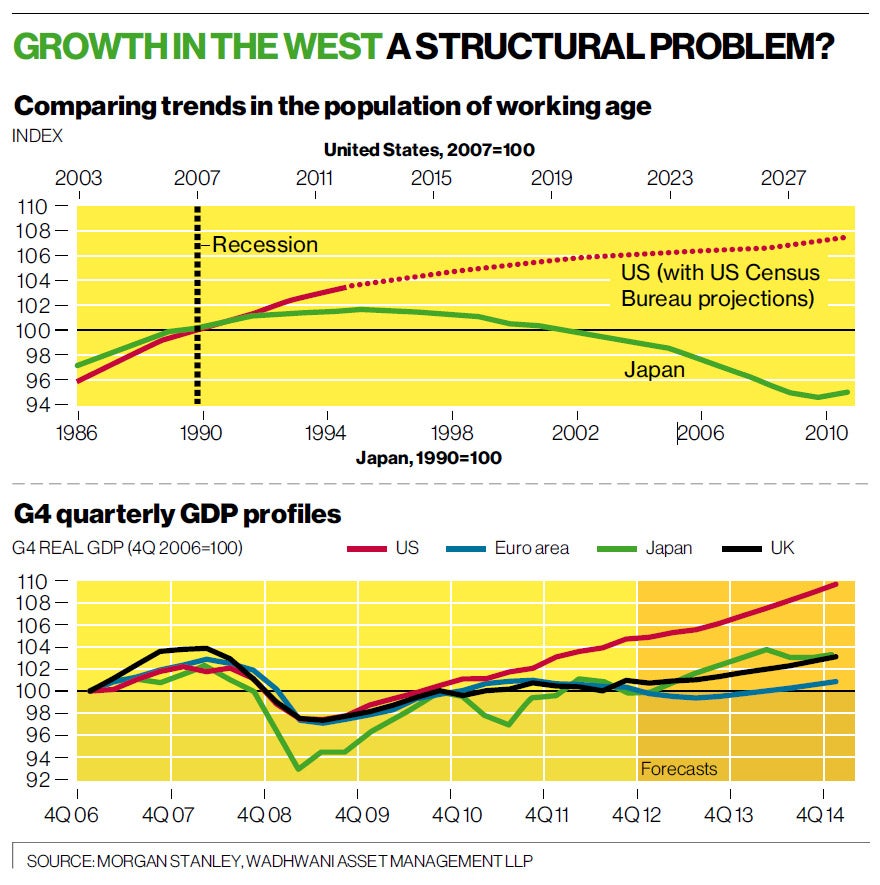

You can see the pattern in Japan set alongside that of the US in the top graph. Start from the point at which both countries hit their peak output, 1990 in the case of Japan and 2007 for the US. The size of the Japanese population of working age started to decline within five years, whereas the US working population has continued to rise.

The graph comes from some work by Citi Economics and was shown in a lecture at Queen Mary College last week by Dr Sushil Wadhwani, the former MPC member who now heads an asset management company. The answer to the question posed in his lecture "The Great Stagnation: What Can Policymakers Do?" was that the UK is not Japan and that in the short term at least more aggressive monetary policies could boost demand. But we would have to be careful that higher inflationary expectations and/or a disorderly fall in sterling did not undermine asset prices and undermine the policy.

Some of these thoughts are echoed in a paper by Morgan Stanley on the global economic outlook. Their projections for growth of the US, Japan, the euro area and the UK are shown in the bottom graph. As you can see, the US is the only part of the developed world that has experienced sustained decent growth. By contrast Japan has bounced up and down, the eurozone is back in recession and the UK is managing only a modest recovery.

The broad theme of this paper is that we are moving from twilight to daylight, with the growth in the second half of the year gradually picking up pace. As far as the US is concerned, Morgan Stanley expects a shift to faster growth to occur in the middle of the year. For the UK, the bank feels there will also be such a shift, though a more subdued one; it also says there is no "silver bullet", no policy shift that will suddenly increase growth. There is no room for a general fiscal boost and Morgan Stanley is sceptical about the scope for a major change in monetary policy, given inflationary concerns. Growth will return, but only gradually, and there is not a lot that can be done about it.

This surely makes sense. But it is not an easy stance for any government to sustain. Yet if the structural growth prospect for the country is unchanged – if the UK can still grow at the long-term historical rate of about 2.5 per cent a year – then it is reasonable to expect that we will gradually revert to trend.

In the case of Japan, economic stagnation was probably inevitable, given the shrinking workforce. In the case of the US and UK it isn't.

But there is still a puzzle. Why is the US doing so much better than the rest of us? There are particular reasons why you might expect it to do better than Europe, because much of the eurozone has the wrong exchange rate. Local conditions across southern Europe require a cheaper euro but there is no way of engineering that at the moment.

For us, well we do have a cheaper pound but that does not seem to have stimulated demand as one might expect it to do. That may be because our principal market remains Europe, where demand is depressed. It may be because of the J-curve effect. This is where initially a fall in the exchange rate reduces foreign income in sterling terms because of the fall of the pound, and only later increases income as volumes pick up. But it may be because price matters less now in international trade, and other factors such as quality and proximity to markets matter more.

At any rate for the time being we have to rely on domestic demand to sustain economic activity and that is compressed by high inflation and slow wage growth. Those of us who hoped that by now real incomes would be rising have been disappointed.

The key structural question is whether something has happened as a result of the cycle that damages long-term prospects. It is hard to answer this, certainly right now when we have yet to emerge properly from the downturn. In the early 1980s there was concern that long-term growth had been undermined by the disruption of the recession: companies went bust and as a result capacity has been permanently destroyed. During the past couple of years a reverse argument has been advanced. This is that because too few companies have gone under, we have not had the rejuvenation of the corporate structure that recession should have brought.

There is no way of testing which argument is more powerful, except that it is worth noting that in social terms keeping companies going causes a lot less distress than letting them go under.

My own feeling about all this is that while there is little evidence that the UK is in the same bind as Japan, if we do want faster growth we will have to remove some of the roadblocks to it – of which the most serious probably are planning controls. But that is another story.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks