Hamish McRae: The mathematics add up to disagreeable events ahead

Economic Life: Portugal and Greece are going to see another year of deep recession

The timescale has shortened. EU summits used to buy three months' calm; then that fell to three weeks; now they are lucky to get three days; next time it may be three hours. And then? The game is over and the European Central Bank will have to print the money.

The aftermath of last week's summit has been fascinating in that it did take about three days before people realised that there really was no agreement. There is a promise of a new treaty for the 26 members designed to create some fiscal compact, but actually that treaty may well not happen. Even if something were approved by all 26 legislatures, the chances of those countries sticking to it would be close to zero. The UK refusal to sign has at least the advantage of openness, even if its use of the veto was handled in a clumsy manner.

So if there is no treaty, what then? Well, we have had a glimpse of the result in the markets this week.

Yesterday, Italy managed to borrow €3bn (£2.52bn) for five years, but it had to pay 6.47 per cent, the highest level since May 1997. It has another €53bn to repay in the first quarter of next year, out of a total of €157bn of eurozone debt. So the danger of a failed auction is huge.

I suppose the Italian banks might buy the stuff then use it as collateral to raise cash from the European Central Bank, but then the ECB would in effect be printing the money to cover the Italian deficit.

Poor Mario Monti, the new Italian prime minister, is in something of a pickle. On Tuesday evening, just ahead of this most recent auction, he told a parliamentary committee: "We are confident that markets will react positively to the efforts Italy is making, maybe not tomorrow, but the reduction in borrowing costs that we anticipate in the coming months will help spur the economy."

Turn that on its head. If Italy does not get the reduction in borrowing costs, higher interest rates will depress the economy – and that is assuming the markets remain open to it.

One reason why they may not remain open will be if there is an "event". That would be some sort of discontinuity in the eurozone, of which the most likely is Greece and perhaps Portugal leaving it. As has been pointed out in these columns and elsewhere, major European businesses are now preparing for such an outcome.

We can see that would have all sorts of difficulties, such as the legal basis on which contracts have been drawn up. Thus if, say, the euro were replaced by the new drachma, contracts under Greek law would simply be honoured in drachma, converted at the new rate.

When Ireland broke the link with sterling, people in Ireland got their money in Irish pounds, not sterling.

But international contracts might have to be honoured in the original currency – in Greece's case euros. So any devaluation would increase the drachma-denominated payment, unless of course the payer defaulted, a not unlikely occurrence.

One of the arguments against a country leaving the euro is that the subsequent devaluation would mean that its debts would be much larger. But if it wasn't going to pay them anyway, it might as well be hanged for a sheep as a lamb.

There is the further issue, which is whether Greece leaving the eurozone would lead to a wider break-up, and if so, what might the timescale be.

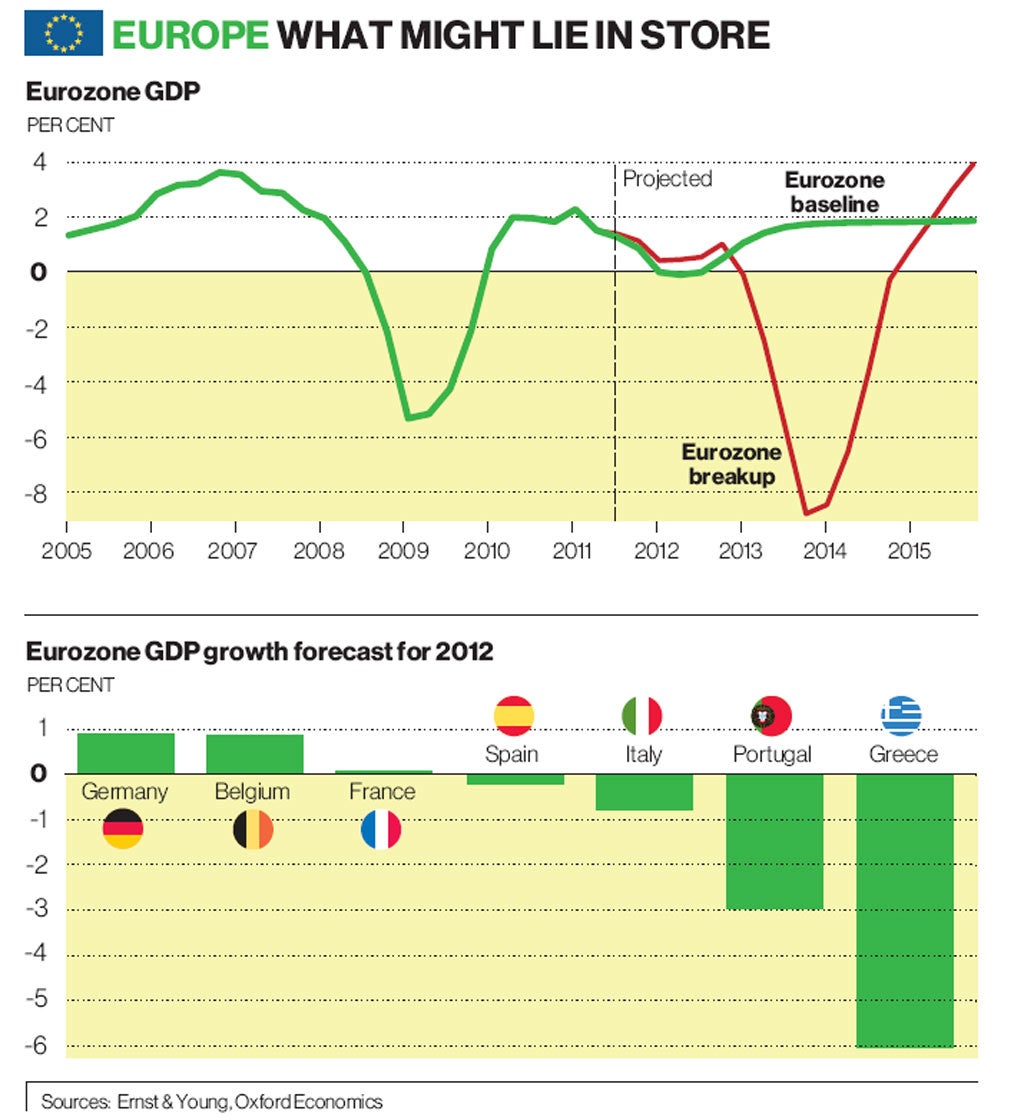

The top graph shows some projections, with a baseline case of no break-up and an alternative break-up scenario. It comes from some work by Oxford Economics for Ernst & Young.

As you can see, were the break-up to occur, they expect a recession even deeper than in 2009. Intuitively, I think that is too gloomy, but let's accept that it might be right. Now look at the ultimate outcome: faster growth from 2015 onwards than would otherwise be the case.

In other words, there would indeed be a short-term cost from the disruption but there would also be a long-term gain.

On this particular projection it would take many years before the lost output were regained, so if it were right there would be an economic case for trying to preserve the eurozone. But the costs of so doing are evident in the bottom graph, which shows some projections for growth next year. Portugal and Greece are going to see another year of deep recession, while Italy and Spain go backwards too.

It may seem an obvious, mathematical point, but if a country's GDP declines, its debt as a proportion of GDP rises. So it has to run even harder, piling on more austerity, just to stay in the same place. Worse, it has to pay a higher interest rate, so it has to run harder still. That is the point at which lenders simply cannot justify making more funds available and default becomes inevitable. Prepare for a wave of sovereign defaults in Europe over the next three years.

None of this is new. It is just that this week the mathematics have become that much clearer.

Had the eurozone leaders last week focused on increasing the firepower of the various support funds instead of the longer-term and vaguer goal of a fiscal compact, maybe they could have bought more time. Had they accepted the UK demands and managed to get some kind of tacit British support for the fiscal compact, that would at the margin have given it a little more credibility. But eventually the maths would have taken control again.

What happens next? As far as the markets are concerned things may well quieten down for the rest of the year. There may well be a downgrading of French and other eurozone debt, but the rating agencies are following the market rather than leading it.

The big events will come next year, and disagreeable they are likely to be.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies