Hamish McRae: Power will shift from the West but the rich will still be rich in 50 years' time

Economic Life: Present and continued prosperity is based on open borders. It is easy to look back and see how protectionism has wrecked the creation of wealth in the past

Will the shift of economic power away from the West really happen as swiftly as has been predicted? Hardly anyone doubts that the shift is happening and will continue to do so. Nor is there any doubt that the recent recession speeded up the process. Last year China passed Japan to become the world's second-largest economy, second that is after the US, some years earlier than had been predicted. But there is a real debate about the pace and timing in the future.

The whole debate was kicked off nearly a decade ago by Goldman Sachs, who coined the cute acronym of the BRICs, thereby pulling together the four largest emerging economies of Brazil, Russia, India and China. Goldman built a computer growth model that made some predictions of the rate at which the Brics would overhaul the G7, predictions that so far have in anything understated the pace of change. Goldman also has helped focus attention on the other big emerging economies, such as Indonesia, Nigeria and South Africa, dubbing them the "Next 11". The most recent runs of the Goldman model, done before the full scale of the recession was clear, had China passing the US to become the world's biggest economy in 2027.

Since then there have been various other estimates of the pace at which China might overhaul the US. PricewaterhouseCoopers predicted that this might happen about 2020. Some work at the Carnegie Institute had the year 2035. If you take currencies at purchasing power parity, rather than official exchange rates, there have been suggestions that China is already approaching the US in size. It is already the world's largest exporter, having passed Germany last year, and the world's largest producer of many items, ranging from steel to socks.

I have just been looking, however, at some work by Karen Ward at HSBC, which suggests that though this big picture of China passing the US is right, the whole transition will take longer than has been predicted by others. The paper, "The World in 2050", focuses on that particular year and does not give a specific year when China might pass the US, but it is implicit that this will be some time in the 2040s, ie, later than most other predictions. Come to the reasons why in a moment – first, what are the main points?

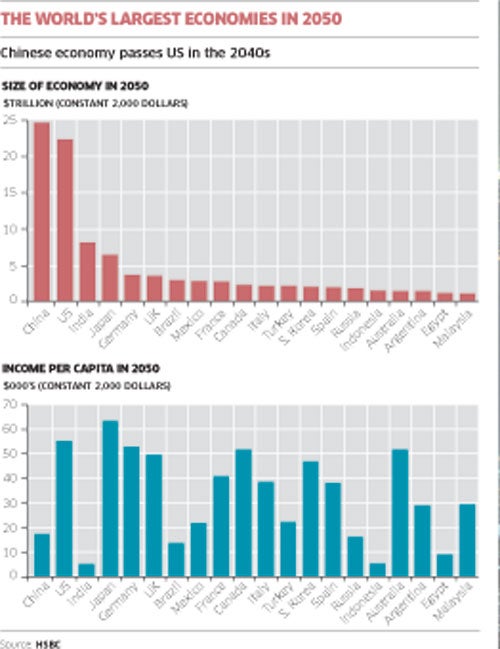

Start with the pecking order for 2050, as shown in the top graph, which shows the top 20 (the full report takes into account the top 30 nations). It will be very much a two-horse race, for though India will have passed Japan, it will not be that much bigger, and Brazil and Russia will remain smaller than Germany and the UK, with Russia much smaller. Indeed on these calculations both the US and the UK do rather well, losing power only slowly.

The big losers in relative terms are the small-population ageing European nations, such Switzerland, Sweden and the Netherlands. The big gainers (aside from China and India) are the other emerging economies, such as Mexico, Turkey, Indonesia, Egypt, Malaysia and so on.

If you look at wealth per head, though, the present developed world retains much of the relative position it has at the moment, as the bottom graph shows. Thus Americans will still be three times richer on average than Chinese. The Japanese will be the wealthiest people on earth, while Britons, Germans, Canadians and Australians will also be relatively well-off – welcome news for Aussies in these dark times.

This report raises a host of questions, ranging from why the power shift should be happening a bit slower than some others have predicted, to what might upset this broadly optimistic outlook of steadily increasing world prosperity. Perhaps the best way of getting a handle on the former is to look at the reasons why countries grow and why they fail to do so: "why so many of the emerging markets are now managing to 'catch up' having failed so miserably to improve living standards through much of the 20th century".

The paper leans on the work of Professor Robert Barro of Harvard University in looking at what determines income per head. He identified three: economic governance, human capital and the starting point for income per head. That last might seem a bit odd but of course, if a country is rich already, with all the economic infrastructure such wealth has created, it takes a lot to dislodge that position, whereas if it is poor it takes a lot to crank up wealth.

On the first, many countries in the emerging world made a lot of policy mistakes: the command economies of Communism misallocated resources; Latin America failed to instil monetary discipline, while India imposed bureaucratic restrictions on economic activity. Democracy on balance helped but some authoritarian regimes nevertheless did maintain the rule of law and property rights.

On the second, human capital is the key to increasing productivity, not just because there is not much point in having the latest technology if you don't have the people to get the best out of it. There is also the need for people to be adaptable, so that as the need for different skills changes, the workforce can, so to speak, "retro-fit" itself with the new skills.

Once you have worked out what might happen to income per head, you can then look at population projections and see what might happen to the overall size of the economy. Here the UK is interesting because on these projections Britain becomes the largest European economy in terms of people, with 72 million compared with Germany's 71 million and France's 68 million. The UK will on these projections still have a slightly smaller economy than Germany because we will have a lower income per head. But the idea that Britain might become Europe's most populous country is something that has not I think entered most people's heads – a parochial point but an interesting one, surely?

And the bigger matter of whether it is sustainable for global output to triple over the next 40 years? The answer in this paper is a cautious yes. The author looks at the position in a number of different ways. There certainly has to be a huge increase in sustainable energy production but there also has to be much better use of energy too. The world has to use water better. And it has to accept that things might go wrong.

The final part of the paper looks at the possible flaws in its relatively rosy outlook. The big point it makes here – and I think this is absolutely right – is that present (and continued) prosperity is based on open borders. Trade, resources and finance must keep flowing and it is easy to look back and see how protectionism has wrecked the creation of wealth in the past. As the last century demonstrated, human beings are perfectly capable of making huge mistakes.

We will see. For myself at least, the main function of this sort of exercise is that it makes it clear to everyone how great the potential prize is, if that is the world maintains its present progress towards a more-open economy. Think of the progress in China and India over the past 30 years and project that forward. That is huge.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies