Hamish McRae: Sense of foreboding in markets is not warranted by world growth prospects

Economic Life: The world economy will continue to grow through the economic cycle but much of that growth will be in the emerging world rather than the developed one

The markets are being too gloomy about the recovery. If that sounds a bald (and bold) statement, let me put the point a bit more precisely. There are many reasons to expect that the recovery, both here, in the US and elsewhere, will struggle in the coming months. I happen to think it likely that there will be some sort of double dip, though not a return to actual recession. But while there are plenty of reasons to be cautious, they warrant neither the present sense of foreboding in the markets, nor indeed the barrage of criticism that the US policymakers in particular have been subjected to.

Leave the latter point aside, for once the recovery is secure that noise will die away, and focus on the markets. Shares here and elsewhere are in some sort of bull market but have just experienced a sharp correction. August was indeed a wicked month for share prices but that does not alter the scale of the recovery since March last year. The issue now is whether the markets are over-discounting the difficult period for the world economy. In other words there are sound reasons for being cautious, but not as cautious as the markets currently are.

The caution shows in two ways: relatively cheap equities and extremely expensive bonds. If the former are somewhat of an anomaly, the latter seem to me to be pretty mad. US 10-year Treasury bonds yield about 2.6 per cent at the moment. So what is US inflation going to be over the next 10 years? This is a country with a national debt equivalent to 66 per cent of GDP, with the likelihood of it reaching 80 per cent or more. So there will be huge political pressure to inflate away the real value of this debt. So is inflation likely to be higher or lower over the next 10 years than it was over the past? If you think higher, you would be mad to buy US Treasuries.

Or take the UK. Ten-year gilts yields are just under 3 per cent, having nudged up a little in the past few days. But is inflation going to average less than 3 per cent over the next 10 years, given that the RPI is up 4.8 per cent over the past year and even the discredited CPI up more than 3 per cent? You have to be hugely naïve to think that.

The only reason for wanting to lock away cash for a decade and get only a nominal 3 per cent return (and almost certainly a negative real return) is if you think other investments will be even worse: in short, if you are profoundly gloomy. And indeed that is what the markets are at the moment.

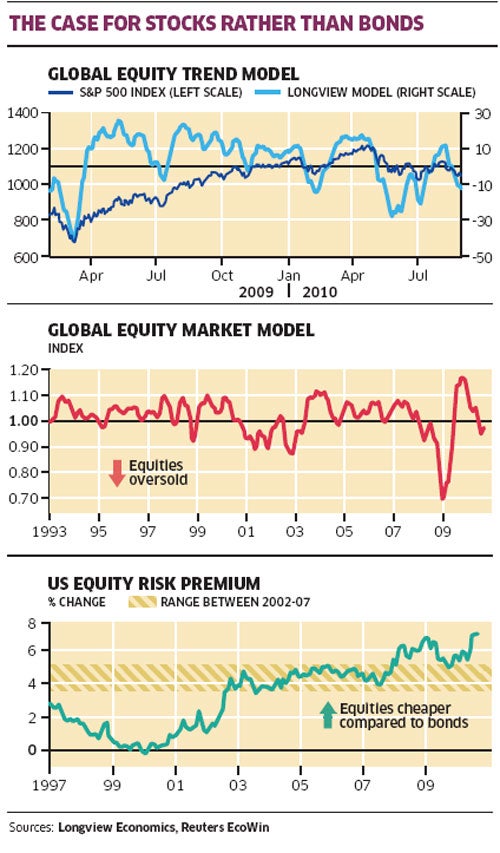

The blue line in the top graph shows what has happened to US share prices over the past 18 months, together with an index created by Longview Economics to capture the longer-term trend. This index, shown in the gold line, aims to give "buy" and "sell" signals: low is buy, high is sell. As you can see it was shouting that people should buy shares in the spring of last year (as these columns reported at the time), but since then has been more ambivalent. But it has been broadly supporting in recent months and is back giving a buy signal at the moment, albeit a weak one.

The next graph, also from Longview, confirms this. It shows the extent to which global shares are overbought or oversold over a longer period. I suppose you could say it reflected optimism and pessimism about equities as an asset class. As you can see by the end of the 1990s it had spent a lot of time in the overbought region, but then signalled that people had gone cold on equities through from 2000 until 2004. Investors went passionately anti-equities in the latter part of 2008, and the early part of last year recovered their optimism, but only now to plunge back into despair. The message is that you should sell when everyone else is starry-eyed and buy when everyone else is glum.

A further measure of the disdain for shares is the equity risk premium, a measure of whether equities are cheap or expensive relative to bonds. The final graph shows how before 2002 shares were basically expensive relative to bonds but how since the crisis they have become cheap.

Put all this together and what do you get? Let me set out some propositions to be agreed with or disagreed with as you feel fit.

The first is that the world economy will continue to grow through the economic cycle, but that much of the growth will be in the emerging world rather than in the old developed one.

The second is that large western companies will benefit from this growth, either directly though exports and investments or indirectly through (slowly) rising incomes at home.

The third follows from this: that while the case for buying shares is not overwhelmingly strong, as it was in March last year, this is not a seriously stupid time to do so. The markets of the developed world are not going to make huge progress over the next couple of years but they are unlikely to tank, even assuming that there is some sort of double dip.

The fourth is that policies in the West will remain broadly supportive of growth. Fiscal deficits will be cut, as they have to, and this will be a drag on the growth of consumption. However it will not derail the recovery. It will at worst slow it a little and at best be neutral. Monetary policy will remain lax, with central banks continuing their various versions of printing money for the time being.

My final proposition follows from this. It is that as governments gradually correct their fiscal deficits and central banks eventually reverse their money-boosting activities, there may well be an adverse reaction in the markets. That reaction will start in the bond markets, where people will appreciate there is something of a bubble. If you agree with me that those 10-year yields fail to discount the risks that national governments have run by jacking up their deficits, then yields have to rise and, mathematically, bond prices have to fall. Bonds are far too expensive.

If this line of argument is broadly right, we will have a bear market in bonds. It may be that one is beginning now, for there has been a great deal of debate as to whether there is indeed a bond market bubble. I cannot pretend to be able to see the shape of the bear market; just that what is happening now is unstable. Instinct says that there will be some national defaults, most obviously led by Greece, but that these are at least four or five years away. The danger is that default will become respectable. Politicians will blame bankers, the markets, whatever, rather than themselves and may follow destructive policies. Eventually fiscal discipline will be restored, just as monetary discipline was restored after the great inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s. But it will be tough and take more than one economic cycle.

In these conditions, what happens to share prices? If there is a bear market in bonds, can there be a bull market in equities? Again I cannot give a good answer, but put it this way: there is a bubble in bond prices but not in share prices. So surely shares are the safe haven, or at least the safer one.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks