Hamish McRae: Short-term fix over US debts could undermine long-term solutions

Economic View: Americans are paying for a government that is only about four-fifths the size of the present one

There is a difference between "can't pay, don't want to pay", "can't pay, but would pay if we could", and "can pay, but may not do so". The first is Greece, the second Ireland, and the third the United States of America. This is a fiscal matter rather than a monetary one but it may well create a fascinating dilemma for the Federal Reserve and its new chairman, Janet Yellen.

The markets have become accustomed to coping with the first and the second, albeit alternating between bouts of gloom, panic and in the case of Ireland at least, modest optimism. But they are really struggling to cope with the third. How should you treat the debt of a reasonably solvent borrower which might, as a result of a domestic squabble, just not bother to pay the interest on the money it has borrowed?

The initial reaction was insouciant. The US could of course meet its debts and politicians always managed to sort something out when they had to. The so-called shutdown? Well that had happened before and did not seem to matter too much. That mood has now shifted as people start to focus on the more serious matter of a failure to raise the debt ceiling. There are two issues here, a short-term one and a broader, almost philosophical one. A word about each, and then some thoughts about the dilemma for the Fed.

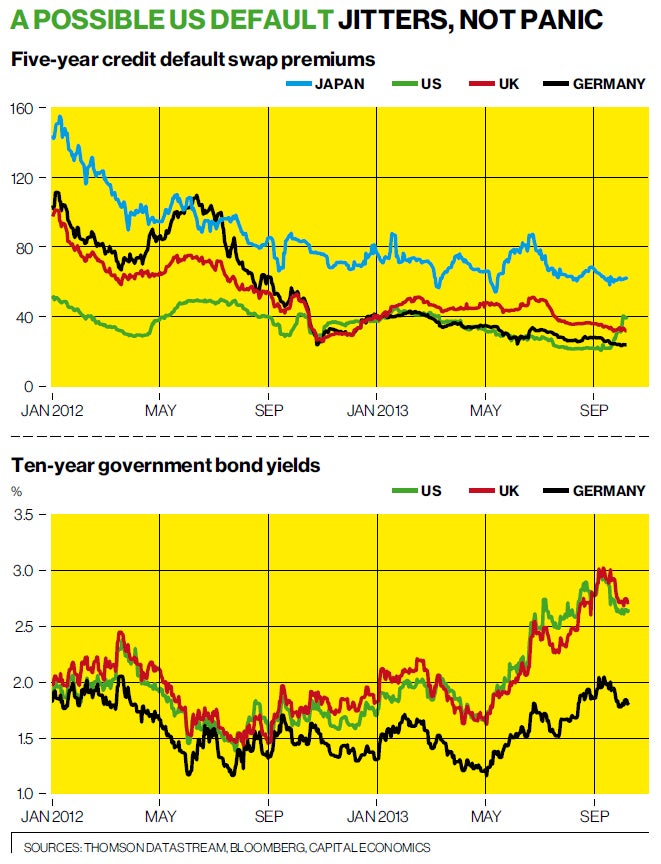

What has happened in the past few days has been a reassessment of the practical consequences of the US failing to pay interest on its debt. The cost of insuring against such a default has shot up, as you can see from the chart on credit default swap rates. In addition, very short-term rates on Treasury bills have also risen, particularly on bills due later this month. These are in effect a substitute for bank deposits, and even a few days delay in an interest payment would be disruptive. Better to stick the money in the bank instead, even if the rate is slightly lower. However, longer-term yields have not moved at all, as you can see from the other graph. This is also in contrast to equities, which have been quite soft over the past three weeks.

So the markets seem to be saying they are worried by the immediate consequences of the Treasury missing interest payments, but not worried about the longer-term solvency of the US. On the surface all this seems to make sense, though it may be underplaying the dangers of a default. But if you unpick a little, the reason why there is a danger of this default is because there is a political impasse that may well affect the country's long-term solvency. The short-term issue is whether there will be a default and what measures the administration may take to avoid it. The longer-term issue, as I say, almost a philosophical one, is what sort of government do the American people want?

At the moment, the Treasury covers something like 81 per cent of its outgoings with tax revenue. It has to borrow the rest. So if it were to cut 20 per cent off its spending, then there would be no need to raise the debt ceiling. Put another way, Americans are paying for a government that is only about four-fifths of the size of the present one. Of course, you can do that for a few years, and Japan has been doing this for a generation. That defers the burden forward to the present voters' children. You can say, and it is true, that the deficit has been narrowing fast. It is approaching 4 per cent of GDP, a lot lower than ours. But we have a credible plan to get back to balance, and the Coalition is starting to talk of the need to run fiscal surpluses. It is certainly very much in the self-interest of the young that we should do so and it will be intriguing to see whether young people get this and start to vote in favour of tight fiscal policy.

The US, however, is not really confronting the need to start running surpluses in any meaningful way. The Republicans, who oppose increasing the debt ceiling, are ostensibly on the side of fiscal responsibility in the sense that they are resisting the government's need to borrow more. But in reality they are doing the reverse, by, for example, refusing to back tax increases and using the debt ceiling as a weapon.

So what should the Fed do? If there is a default and that default sends a Lehman-like shock through the markets, it has to do what central banks must always do, which is to supply liquidity without limit. But in doing what is needed in the short run, it must not undermine what it has to do in the long. This is to support generally responsible financial policies. Spraying cash around to underpin unsustainable fiscal policy is not responsible.

Civil servant Blanchard should watch his language

A footnote on the new report from the International Monetary Fund, which completely reverses its gloomy judgement in April. It presents the UK's economic position as much improved, but it was perfectly clear then that the recovery was secure, as some of us argued at the time. It is depressing that what was obvious to a hack in London was not obvious to expensive economists in Washington DC, but we all make mistakes I suppose.

What is not excusable is the intemperate way the chief economist, Olivier Blanchard, criticised the UK Government's policies as "playing with fire". That is not appropriate language for any international civil servant and should not happen again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks