A brief history of coronaviruses

From the Sars outbreak in 2003 to the persisting common cold, this isn’t the first time we’ve encountered this group of deadly illnesses, writes Lindsay Broadbent

Most of us will be infected with a coronavirus at least once in our life. This might be a worrying fact for many people, especially those who have only heard of one coronavirus, Sars-CoV-2, the cause of the disease known as Covid-19.

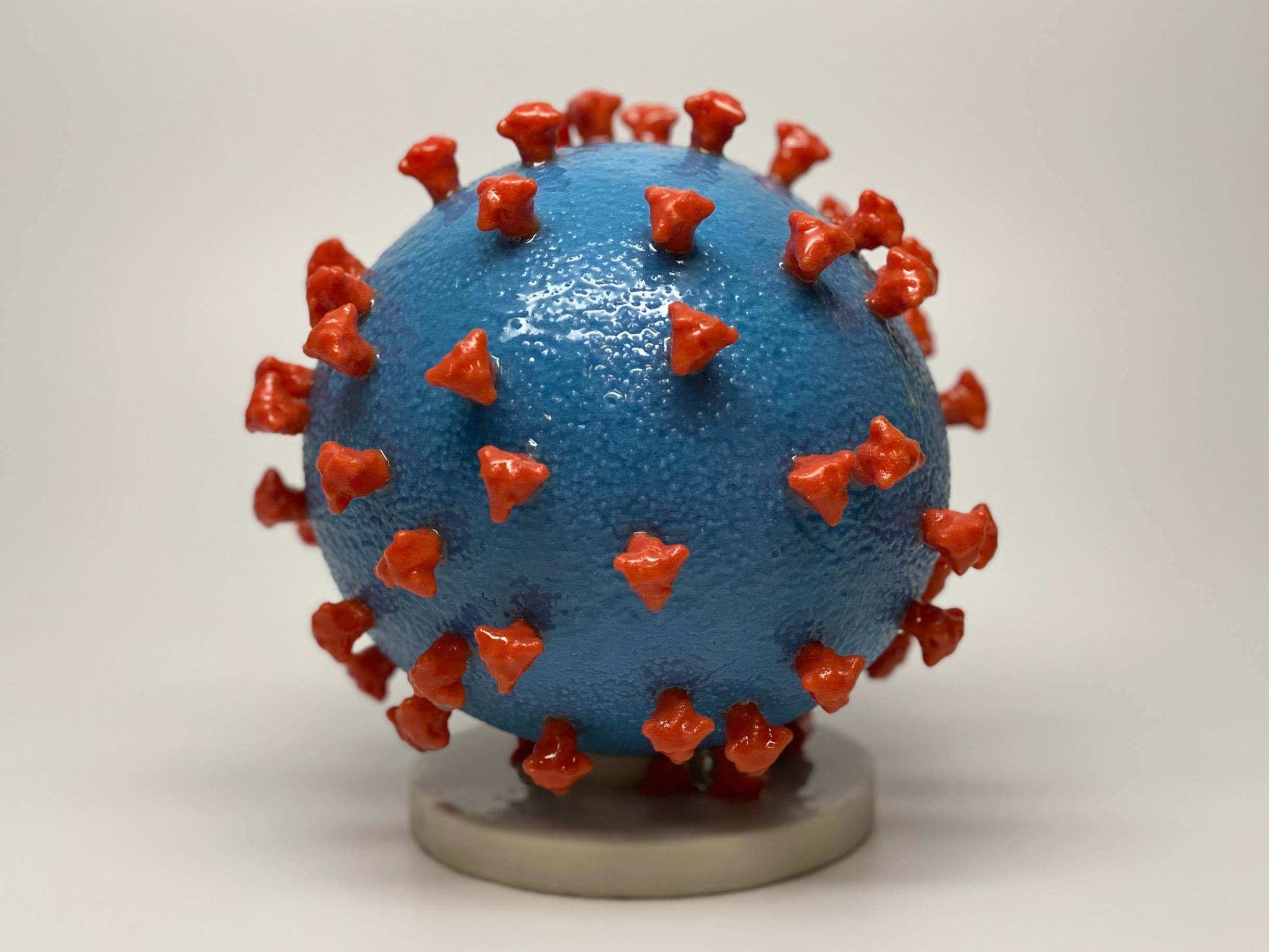

There is much more to coronaviruses than Sars-CoV-2. Coronaviruses are actually a family of hundreds of viruses, most of which infect animals such as bats, chickens, camels and cats. Occasionally, viruses that infect one species can mutate in such a way that allows them to start infecting another species. This is called “cross-species transmission” or “spillover”.

The first coronavirus was discovered in chickens in the 1930s, but it wasn’t until a few decades that the first human coronaviruses were identified in the 1960s. To date, seven coronaviruses have the ability to cause disease in humans. Four are endemic (regularly found among particular people or in a certain area) and usually cause mild disease, but three can cause much more serious and even fatal disease.

Coronaviruses can be found all over the world and are responsible for about 10-15 per cent of common colds, mostly during the winter. The coronaviruses that cause mild to moderate disease in humans are called: 229E, OC43, NL63 and HKU1.

Because it can spread undetected, the numbers of people it will infect and the numbers that will die will be higher than any coronavirus we have ever encountered

The first coronaviruses discovered that are able to infect humans were 229E and OC43. Both of these viruses usually result in the common cold and rarely cause severe disease on their own. They are often detected at the same time as other respiratory infections. When several viruses, or viruses and bacteria, are found in patients this is called co-infection and can result in more severe disease.

In 2004, NL63 was detected for the first time in a baby suffering from bronchiolitis (a lower respiratory tract infection) in the Netherlands. This virus has probably been around for hundreds of years, we just hadn’t found it until then. A year later, in Hong Kong, another coronavirus was found – this time in an elderly patient with pneumonia. It was later named HKU1 and has been found to be present in populations around the world.

But not all coronaviruses cause mild disease. Sars (severe acute respiratory syndrome) caused by Sars-CoV was first detected in November 2002. The cause of this outbreak wasn’t confirmed until 2003 when the genome of the virus was identified by Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory. Sars bears many similarities to the current pandemic of Covid-19. Older people were much more likely to suffer severe symptoms which included fever, cough, muscle pain and sore throats. But there was a much greater chance of dying if you had Sars. From 2002 until the last reported case in 2014, 774 people died.

A decade later, in 2012, there was another outbreak involving a newly identified coronavirus: Mers-CoV. The first case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) occurred in Saudi Arabia. There were two further Mers outbreaks: South Korea in 2015 and Saudi Arabia in 2018. There are a handful of Mers cases every year, but the outbreaks are usually well contained.

So why did Sars or Mers not result in pandemics? The R0 of both Sars and Sars-CoV-2 is about two or three (although some more recent estimates of the R0 for Sars-CoV-2 are around five), meaning that every infected person is likely to infect two or three other people. The symptoms of Sars were more severe, so it was much easier to identify and isolate patients.

The R0 of Mers is below one. It is not very contagious. Most of the cases have been linked to close contact with infected camels or very close contact with an already infected person.

One of the main challenges in containing the Sars-CoV-2 outbreak is that symptoms can be very mild – some people may not even show any symptoms at all – but can still infect other people. Sars-CoV-2 is not as deadly as either Sars or Mers, but because it can spread undetected, the numbers of people it will infect and the numbers that will die will be higher than any coronavirus we have ever encountered. So please, stay at home.

Lindsay Broadbent is a research fellow at the School of Medicine, Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences at Queen’s University Belfast. This article first appeared on The Conversation

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies