Wes Streeting’s cancer plan is admirable – but it’s not the silver bullet the NHS needs

The government has published a plan with strong promises for NHS cancer care. But will it be a hostage to scientific developments – and is it getting the ‘basics’ right? Rebecca Thomas takes a look

The government has published its 10-year plan to turn around NHS cancer services in England and there are some big promises in there, including the ambition to meet all waiting time standards by 2029. Labour also says that, from 2035, it will have 75 per cent of patients who are diagnosed with the disease declared as cancer-free or living well after five years.

The scale of such promises has not been seen since the 2000 national cancer plan, published under Tony Blair’s Labour government, when the flagship 62-day cancer treatment time standard was first introduced.

The latest plan is, of course, laudable, and shows a commitment to tackling what is one of the biggest health battles for Britain.

But many of the promises – such as early intervention through wearable technology, cancer vaccines and advanced blood and saliva tests – rely on the development of new technology, meaning the plan may be hostage to scientific and medical developments that are yet to materialise.

NHS has ‘mammoth’ hill to climb

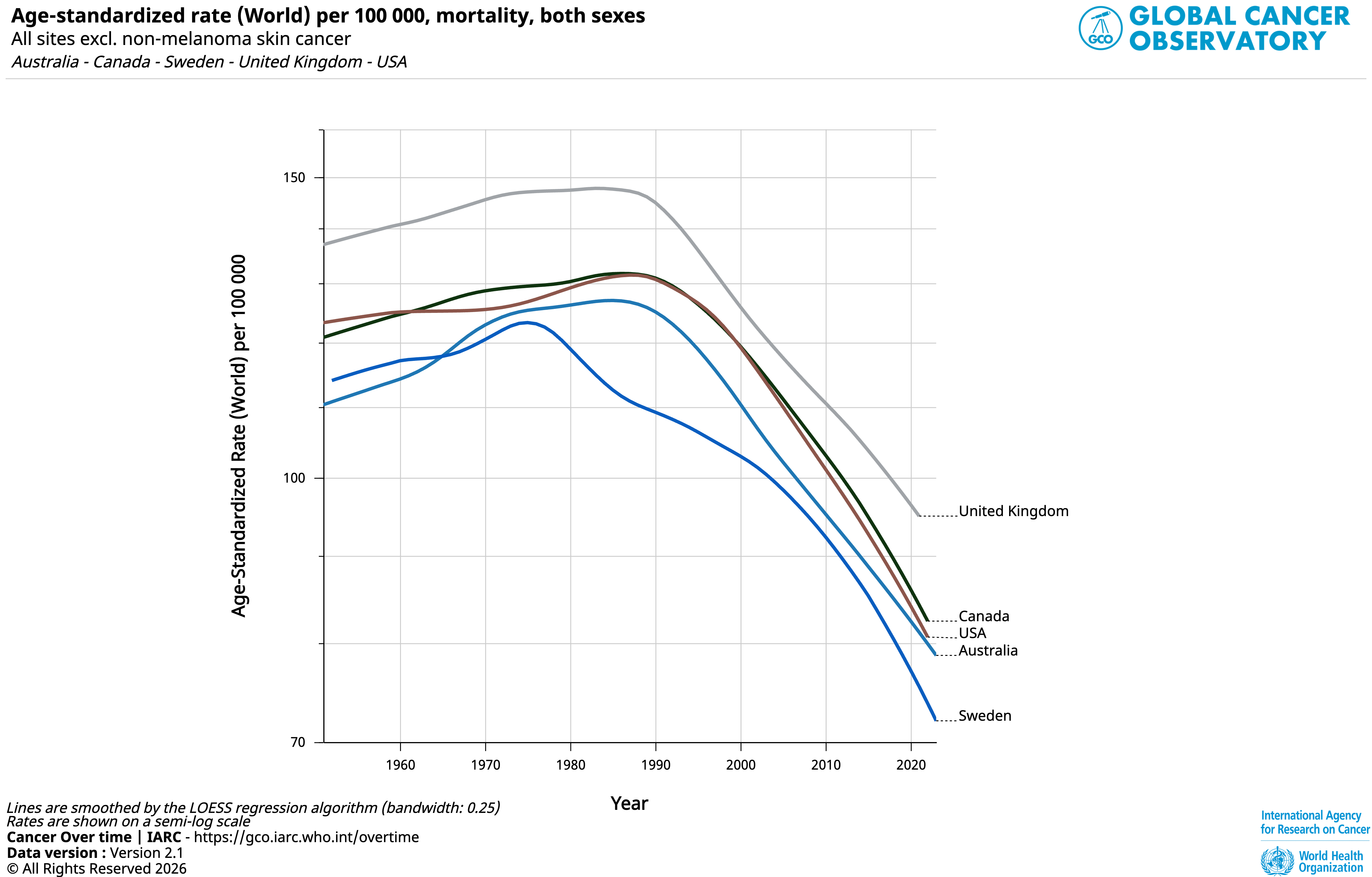

Data published by the World Health Organisation shows, based on 2021 figures, that the UK had a death rate from cancer of 94 per 100,000. This compares to 80 and 84 in Australia and Canada, respectively. Sweden has the lowest mortality rate at 71 per 100,000.

Cancer experts have pointed out that the NHS’s ambition to meet the waiting times target will be a “mammoth” task.

Data from November 2025 suggests the government will have more than a mountain to climb for any specific cancers, including head and neck, gynaecological, gastrointestinal, urological, and lung cancers, with 70 per cent of patients currently being treated within the 62-day target.

The Nuffield Trust points out that, if the government is to meet its 2029 ambition, NHS services will need to increase the proportion of patients seen each month by 30 times the current rate.

Sarah Woolnough, chief executive for health tank The King’s Fund, toldThe Independent: “It is a mammoth task to remeet the [national] standards within three and a half years from where we are now.”

This task comes as more people are being diagnosed and coming forward for cancer. Not only does the NHS have to meet standards it’s been unable to meet for a decade, it will also have to meet them with greater demand coming down the line.

Ms Woolnough said: “Overall, the plan is rightly ambitious. This plan is asking for a big step change in the day-to-day operation management of cancer referrals and cancer diagnostics in a way that hasn’t happened for the last decade.

“The credibility of the plan lies in whether you can focus on fixing the basics… while at the same time having enough capacity and headroom to shift pathways to ready the systems for innovations that will hopefully come through. Some of which is less certain.”

The ‘shiny’ and the ‘boring’

Much of the new cancer plan rests on scientific advancements and technology which are yet to come and yet to be proven in terms of their benefits to the whole health system. This could prove to be a big gamble for the government.

One such tool is the so-called “multi-detection cancer tests”. These tests, which are being widely trialled, can use blood, urine and saliva tests to pick up cancer patients who don’t yet have symptoms.

The government has said that, subject to the evidence, multi-cancer early detection tests can become part of our national screening programmes within the next decade.

Speaking with experts ahead of the plan, most had warned that there are big questions over whether these multi-detection cancer tests are actually proven in terms of their benefits to the overall population, and whether they will actually reduce deaths from cancer.

Speaking to The Independent, Naser Turabi, director of evidence and implementation for Cancer Research UK, explained AI and data, while driving a “revolution in innovation” for diagnosis and treatment, are “definitely not a panacea to improving waiting times”.

“AI and data, more generally, is driving a revolution in innovation, in the approach to diagnosis and treatment. But it needs to be evaluated. I think we're just at the beginning of this wave, and we need to be careful about overpromising how quickly this will deliver, and also, remember that with AI and all research, it doesn't automatically make things cheaper.”

He added: “The hope that they will also make waiting times go down and services more efficient is definitely still to be proven.”

Mr Turabi said it was just as important to focus on the “boring” issues, such as access to GPs and making sure all hospitals are meeting access times, as it was to focus on “shiny technologies”.

Ms Woolnough added that the plan talks about the “new and exciting” but added: “Really, we’ve just got to consistently get test results back to people.”

Se also explained that while innovations are always coming through within cancer treatment, the NHS as a system will have to be ready to implement these advances.

For example, an early cancer may be picked up by a multi-detection cancer test, but will the NHS then have the scans that can diagnose those early-stage cancers? At the moment, it doesn’t seem so.

Who will deliver services?

The major omission in the document is detailed plans for the NHS workforce.

The plan promises to focus less on overall numbers and instead look at the type of roles needed, which will be welcomed.

But it is light on specific promises in relation to the staffing, which quite often happens when governments publish big policy papers.

Leading medical colleges, such as the Royal College of Radiologists and the Society of Radiographers, have already made clear that an adequate boost to the workforce and funding will need to follow the plan.

Ultimately, the NHS can rely on new technology. But, if there aren’t the specialist staff to carry out the new tests and treatments, will it have the right impact?

Time, and the details that follow, will tell.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks