Australia grapples with soaring sexual assaults on campus, and reprisals against victims

Australian universities have some of the highest rates of reported sexual assault in the world. And it's not just on campuses. It's a cultural issue born of the hyper-masculine society.

Female students who have spoken out about sexual assault and harassment on Australian university campuses have returned to their dorm rooms to find them flooded with water. Others came home to defaced dorm doors or mattresses that had been urinated on.

When Emily Jones, a third-year student, asked a group of men to stop encircling women during a barroom tradition — in which men drop their pants and sing when the Australian song “Eagle Rock” is played — she was ostracised by friends and condemned by the news media for joining the “fun police”.

“Rather than being happy to make a compromise because so many women were feeling unsafe, they’d rather just keep having a good time,” Jones, 22, said in an interview on campus here. “I was very disheartened.”

Australia has some of the highest rates of reported sexual assault in the world, according to the United Nations, and over the past year a steady stream of on-campus assaults, ritualised misogyny and cruel retaliation have prompted a national conversation about gender, power and accountability.

A January report by the advocacy group End Rape on Campus Australia found that universities had frequently failed to support victims of sexual assault and harassment. In some cases, the report said, they actively sought to cover up sexual assaults to avoid damage to their reputations.

And while the problem is global, each new scandal here — just this week, a young woman accused a Greens party member of date rape — has led to more women speaking out, as well as an angry response from what many Australians consider a core element of this country’s identity: its hyper-masculine culture.

“It is standard, in fact, that when a student exposes sexism or misogyny in their own university they are almost always met with horrendous backlash and ostracism, including reprisals,” said Nina Funnell, a victims’ advocate and writer. “That’s incredibly common in Australia.”

Australian university officials — especially at the two elite universities facing the most criticism, Australian National and Sydney — insist that they are tackling the problem head on. Sydney University recently set up a rape hotline and improved training for staff, said Tyrone Carlin, the deputy vice-chancellor. ANU introduced a sexual consent training course for all first-year students this year, said Richard Baker, the pro-vice-chancellor of the university.

The Australian Human Rights Commission is conducting a survey of 39,000 students at 39 Australian universities to map the full extent of the problem. “All universities are putting in an enormous amount of effort,” said Belinda Robinson, chief executive of Universities Australia, an association of the country’s universities, which helped finance the survey. “This whole-of-sector approach is a world first.”

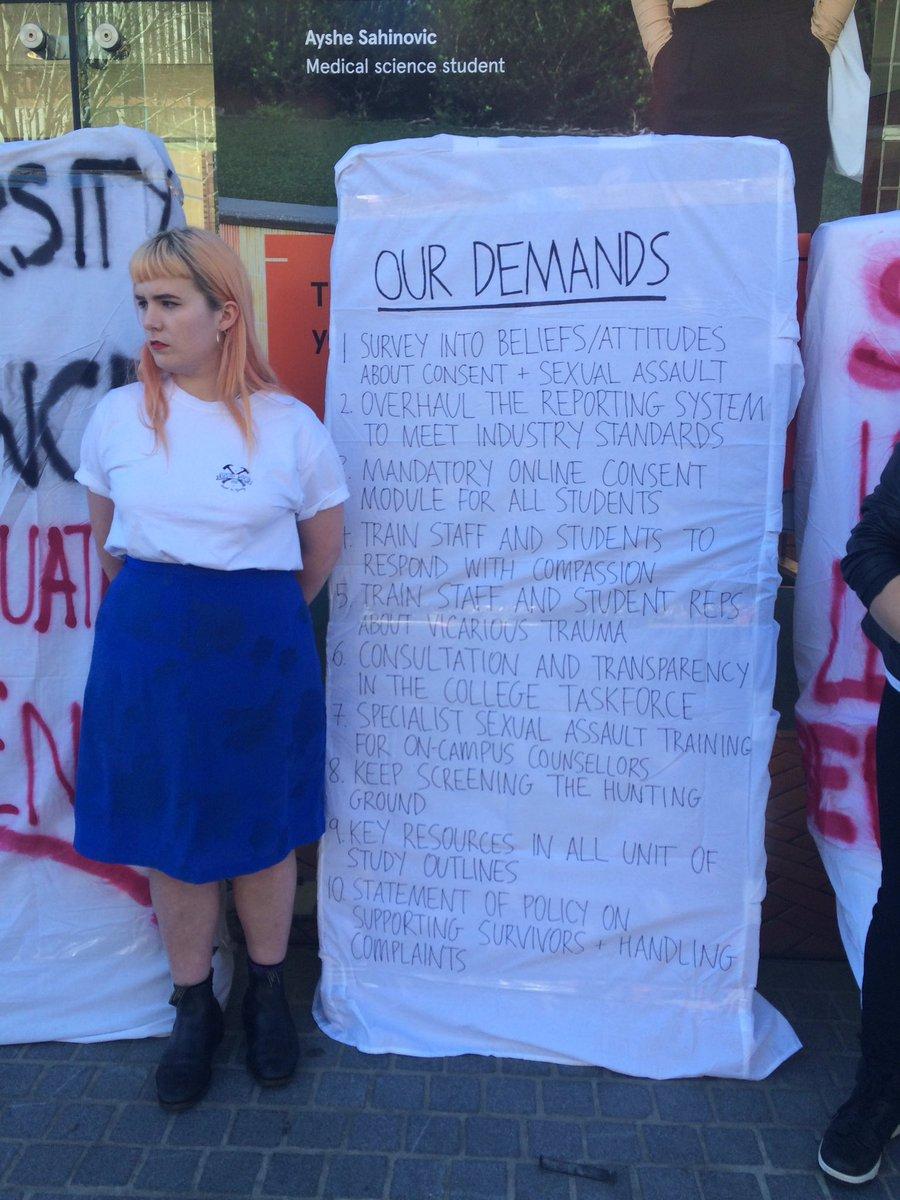

But many students question the universities’ commitment. They say that it is still common for complaints to linger without a university response; for men accused of, say, rating women’s bodies on social media to receive little punishment; and for there to be little coordination at a national level. The activists say their demands are reasonable: a university hotline that offers help from a trained trauma professional, required sexual consent training and a clear and transparent system for adjudicating complaints.

In the United States, where sexual assault on campus continues to be a problem, mandatory consent education has become increasingly common. Databases of sexual assault cases at universities can be easily tracked online, and because of Title IX — a 1972 federal law mandating equal access to higher education — every US educational institution receiving federal funding is required to have a Title IX coordinator, whom victims can contact to report sex discrimination, sexual harassment or violence.

In Australia, many students say that requests for similar policies have been thwarted or delayed even as reports of sexual assault reached a six-year high last year.

At ANU and Sydney, the problems have long been obvious. Last year, in an open letter to Sydney University officials, women who served in student government wrote: “For an entire decade we have been raising the issue of sexual assault and harassment on campus with the administration. For an entire decade we have been met with resistance to change.”

At Sydney University, for example, the Safer Communities Working Group, set up more than a year ago in part to deal with sexual assault, is seen by some students as window dressing. “I was pretty hopeful, maybe naively, coming into it, thinking we could bring students’ concerns there and they would be addressed,” said Anna Hush, 23, a philosophy student who was part of the group last year. “But it was much more them telling us what they were doing rather than us contributing to decisions being made.”

Katie Thorburn, 22, the student government co-women’s officer at Sydney University, said that school officials initially resisted a pilot program for sexual consent education, then bristled at questions about why they ended up choosing a voluntary quiz in which students could skip questions to reach the end. “They’re tougher on plagiarism,” Thorburn said.

A Sydney University spokeswoman said they would review that concern as the program was used more widely.

Some men on campus acknowledged a wider problem — “the treatment of women as sex objects first,” as Harry Licence, aged 20, a second-year media and communications student, put it. In the most recent scandal, a student at St Paul’s, an elite residential college, posted a screed on Facebook comparing sex with large women to “harpooning a whale” and offering advice on how to “get rid of some chick” after “rooting” her.

Licence, who has friends at St Paul’s, said that wherever privileged students from all-boys schools are concentrated, there is a lack of experience with treating women as equals. “I think there are significant issues that come from living within that bubble,” he said.

In Canberra, Emily Jones is still dealing with the consequences of that insularity. The “Eagle Rock” incident happened on the dance floor of a bar in her former residential college, Burton and Garran, during a mixer last August. Ever since she wrote in April about the criticism she received after speaking out about it, she has not felt welcome there.

Residents of her dorm started blasting Eagle Rock, a 1971 Australian rock song often played at rugby games and bars, down the hallways. Some of her friends stopped talking to her and ignored her in the dining hall, common tactics, experts say.

Karen Willis, executive officer of Rape and Domestic Violence Services, Australia, said other standard acts of retaliation include flooding, urinating on mattresses and insults on social media.

At ANU, officials have been grappling for more than a year with sexist incidents, especially in its residential colleges, most of which are independently governed living quarters, similar to US fraternities and sororities.

Last year, university officials discovered a secret online group started by students at John XXIII, a prestigious Catholic residential college, who were sharing pictures of students’ breasts and rating them on Facebook. In March, four male students there were caught chanting graphic sexual rhymes about “nailing” women.

In both cases, the students were disciplined, and some suspended. Burton and Garran Hall has officially prohibited the encircling of women when “Eagle Rock” is played.

Jane O’Dwyer, an Australian National spokeswoman, said the university was working to address a nationwide problem. “It’s a cultural issue in Australia,” she said. “We have a hyper-masculine society.”

That culture, advocates say, means serious cases still go unpunished. “We all know women who have been raped,” Jones said. “What ends up usually happening to the perpetrator is they just either do nothing or move them to another college. It reminds me of the way the Catholic Church moved the priests along.”

The End Rape on Campus report, based on public records at 27 of the country’s universities, found that 575 complaints of sexual harassment and sexual assault made to Australian universities in the past five years resulted in only six expulsions.

Australian National officials say they are still trying to improve their response to the problem.

“The university is reviewing all of its policies and procedures to see if we can further enhance their transparency and fairness,” Baker said.

But the universities have a long way to go if they want to cleanse the toxic atmosphere that drove a Sydney University student to the brink last fall. After she wrote a column in the student newspaper about sexual harassment and assault on campus, the student, Justine Landis-Hanley, was barraged with shaming comments on social media. Classmates stopped speaking to her, she said, even refusing to make eye contact.

Then the personal photos that decorated her dorm door started disappearing, one a day. “What hurt so much was the fact that people I lived with, whom I had come to think of as my family, would purposely try to make me feel like scum,” she said. “They were trying, albeit in a pretty pathetic and cowardly way, to run me out of my home.”

Finally, when there was only one picture left, Landis-Hanley took it down herself. As she wrote on Facebook, “I was taken to hospital that night for being suicidal.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks