Brontë bicentenary: How the literary society is making a comeback from turmoil

A year ago, the Brontë Society was riven by discord and in-fighting. But now David Barnett finds that the future is looking brighter in Haworth

Playwright and novelist Bonnie Greer banging the heel of her Jimmy Choo on the table in a bid to call order. Allegations of a management system akin to infamous East German secret police, the Stasi. People screaming – literally screaming – at each other in the annual general meeting.

Not, perhaps, what you might expect of one of the oldest literary organisations in the world, the Brontë Society, founded in 1893: proponent and curator of the legacy of the famous family that lived in Haworth, West Yorkshire – sisters Anne, Emily and Charlotte, wayward brother Branwell, and patriarch Patrick.

Yet all those things happened over the past two years, when a deep schism was driven into the Brontë Society between those dubbed traditionalists, and those who wanted to modernise.

2015 saw a swathe of resignations from the society – Bonnie Greer, then the president, among them – and the following year’s AGM saw scenes of discord never before witnessed, as answers were demanded about just what was going to happen to the venerable society going forward. What happened was Kitty Wright.

When I meet Wright in her office at the historic parsonage, home of the Brontë family, things certainly seem much more sedate than the breathless headlines of a year ago might suggest.

She has been in office as executive director for just over a year, filling a post that had been vacant for the previous 18 months, a fact that might well have contributed to the growing unrest within the charitable organisation.

“There was perhaps a lack of confidence,” says Wright. “A torpor when it came to planning for the future.” So what did she bring to the party? She smiles. “You might say, an Australian can-do attitude.”

Originally from Perth, Western Australia, Wright arrived in Britain in 1999. She was initially head of communications for the Yorkshire Arts Board, and when that body was folded into the Arts Council in 2003 she took a directorship there, until a restructuring in 2010 when she took redundancy and worked on a freelance and sometimes voluntary basis for a wide range of arts projects.

Wright appears to have boundless energy (“I’m nearly 60,” she offers at one point, which comes as a surprise) and seemingly bottomless wells of optimism, combined with a no-nonsense Aussie air.

It would be quite easy to paint her as the saviour of the Brontë Society, riding in to sort out all this shouting and friction, but she’s having none of that.

“I’m not saying I’m succeeding where others have failed, just that with no-one in this post for 18 months there was something of a leadership vacuum. I suppose if I’ve done anything I’ve tried to create a climate of permission, of optimism and energy.”

She is constantly talking about the hard work of the core management and administration team that is based with her in a few rooms at the back of the parsonage – even as executive director, she shares her office with three other people – and bursts with almost visible pride at the work they do there.

“I would never say I’m proud of them, because that implies some kind of ownership of them, I think,” says Wright carefully. “It’s more that I’m proud to be working with them. They’re all brilliant. I’d die in a ditch for them, I really would.”

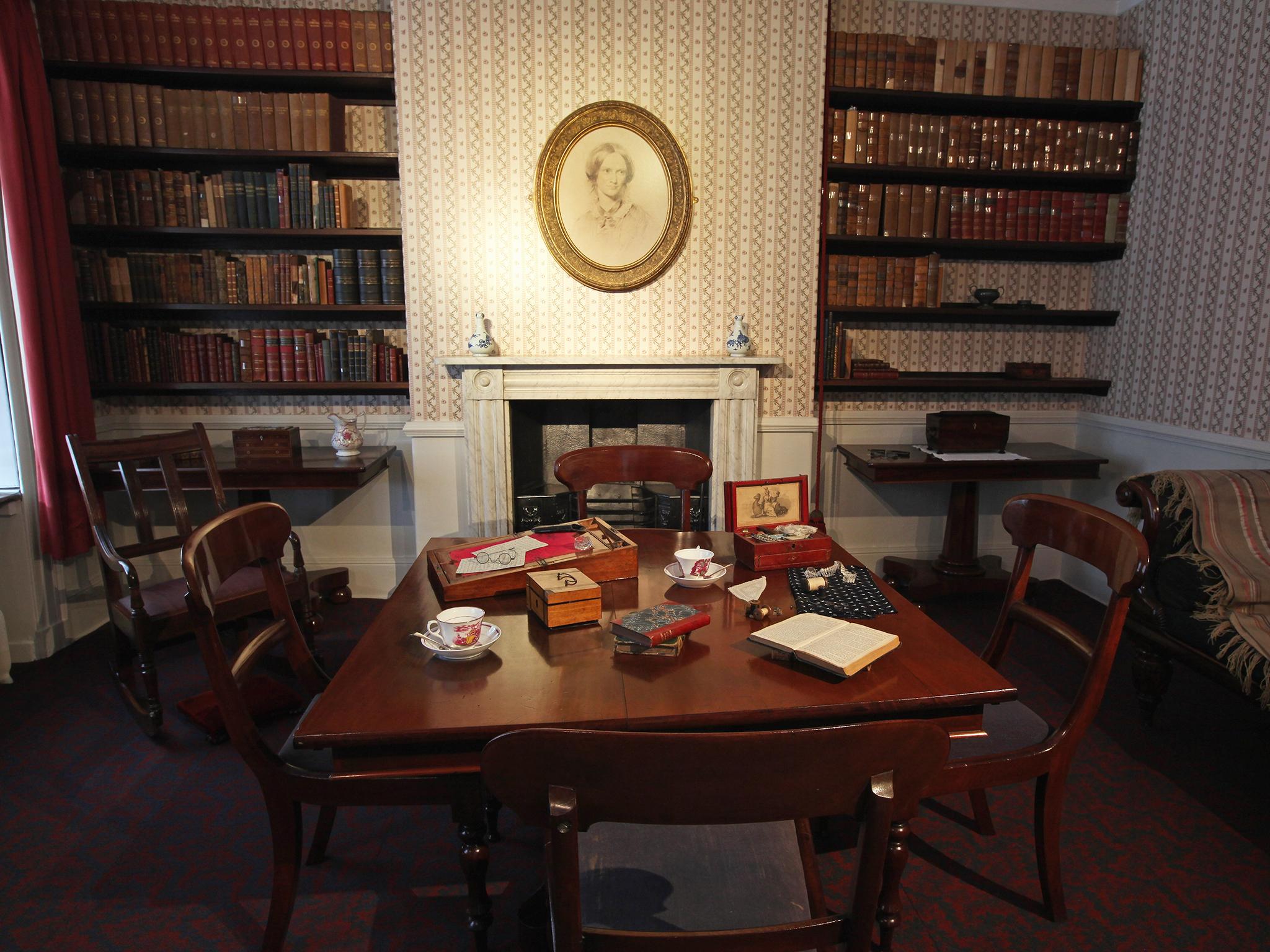

The parsonage museum is the shop-front of the Brontë society, a lovingly preserved homage to the lives of the sisters responsible for such beloved classics of literature as Villette, Jane Eyre and of course, Wuthering Heights.

To tour around the small house at the top of a cobbled lane in the pretty West Yorkshire village, nestling next to the church where the Brontë’s father Patrick was minister, is to step back in time to the mid 19th Century.

And perhaps that’s all that’s required: that preservation in amber of a slice of actual history. Perhaps those arguments between traditionalists and modernisers were all for naught. The legacy of the Brontës speaks for itself. But that’s not quite enough for Wright.

Last week the Brontë Society was named as a new member of a rather exclusive club when it became one of the Arts Council’s National Portfolio Organisations. What this means in real terms is funding of £930,000 over the next four years. Wright was the one who put in the bid, and there are big plans for the money.

“When we knew the NPO round was coming up at the back end of last year, we thought we weren’t ready to apply,” says Wright. “To make a successful bid you have to tick a lot of boxes; you have to prove that you are modernising. Let’s face it, we’ve had some of our grievances aired in quite a public way about that. We knew we had a quality museum, but we also knew we had things to address.”

But the more Wright thought about it, the more convinced she was that the Brontë Society did in fact have a chance. The society is in the midst of a major anniversary: all the Brontës were born across a five year period exactly two centuries ago.

Last year was the anniversary of Jane Eyre author Charlotte’s birth; this year troubled brother Branwell is celebrated. In 2018, it’s Emily, author of Wuthering Heights, while 2020 is all about Anne, who wrote Agnes Grey and the Tenant of Wildfell Hall. 2019 is reserved for father Patrick, and to celebrate his coming to Haworth.

This period of focused looking back at the Brontës’ lives has afforded society a keen opportunity to look forward as well, which Wright seized as the perfect platform on which to stand the bid. And it was successful, opening up a host of schemes which will be set in motion from next year.

The Brontë Society’s raison d’etre is preserving and exhibiting the legacy of the family, and the acquisition of artefacts is going to form a part of their plans for the funding, but they’re also concentrating heavily on expanding their brand globally.

The parsonage already attracts international visitors – a group of Japanese tourists are browsing the exhibits while I’m there – but Wright wants to get the word out with a much stronger online presence. She has a vision of an “augmented reality” website, digital maps, digitised texts from the stock of exhibits: in essence, making their online presence an extension of the physical museum rather than, as Wright calls it, “just an electronic brochure”.

But Wright also wants to diversify in terms of just who visits the museum. Japanese tourists aside, she admits: “We’re not particularly diverse. We’re a bit monocultural.”

A bit white and middle-aged and middle-class? Possibly. But there is relevance among the Brontës’ works to appeal, she says, to a far wider demographic, both in terms of age and ethnic background.

“People might not think the Brontës have anything to do with them,” she says, “but when you read the works you realise that a lot of what they were writing was about ‘the other’: the outsider.”

Wuthering Heights’ brooding anti-hero Heathcliff, who is indeed described in the very first chapter as “a dark-skinned gipsy in aspect,” is a prime example of this.

But there’s also the fact that by the sheer act of writing and seeking publication, the sisters were upending traditional views of women’s roles at that period, and in Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the scene where Helen Huntington slams the bedroom door in her husband’s face was said to reverberate across entire Victorian society.

And what of Branwell? Is there anything more likely to appeal to teenage boys than the mad, bad and dangerous to know artist and his proto-punk rock ethos?

Partnerships with other bodies and organisations to encourage more engagement from under-represented demographics is key to the five-year plan of the Brontë Society – be that schools, higher education establishments, or groups working with black and ethnic minority communities.

And there’s also a bricks-and-mortar aspect to the proposals. Wright looks out of her office window and points to a meadow, beyond the trees that border the parsonage grounds.

“Up there is an underground reservoir,” she says. “It was fed by springs and was built after Patrick Brontë’s work on improving the sanitation in Haworth. We’re hoping to launch a fundraising campaign next year to create a centre for contemporary women’s writing there, a flexible space that could host events, exhibitions, be hired by creative people who want to write, hold classes…”

It’s an ambitious project, Wright knows – it’ll cost between £2.5 and £3m, depending on how easy or difficult it is to run utilities up to it, and that’s without taking into account actually getting planning permission… and what the rest of the members of the Brontë Society think about building on the land.

Ideas and plans come thick and fast from Wright; she’s hoping to encourage better relations with Brontë Spirit, which runs the schoolroom where Patrick Brontë used to teach, and team up with them for potential development of part of their site.

The local authority, Bradford Council is consulting on closing several tourist information centres in the district, Haworth among them. The centre is currently located in a small building that, in 1928, was the first office of the Brontë Society. Wright thinks it would be a pleasing symmetry for the society to take back the building and run the tourist information service from it themselves, as well as providing more space for the management and administrative staff.

There’s another plan as well, which she says is merely “a glint in our eyes”. “Did you see To Walk Invisible? There was a barn in that, that used to stand just outside the parsonage. It would be fantastic to recreate that, make it a curatorial and research space, with an interpretive exhibition, perhaps…”

To Walk Invisible is the dramatisation of the life of the Brontës, written and directed by Happy Valley creator Sally Wainwright, and broadcast by the BBC at the beginning of this year. Has it generated renewed interest in the parsonage?

“It has, but it’s not the only reason our visitor numbers are up,” says Wright. In 2016, they reported a 17 per cent rise in people through the doors, and if 2017 continues on its current trajectory, that will be far exceeded.

“We do have the costumes from the production here, but if that was the only reason people were coming we’d have seen a large spike in attendance and then a drop, and that’s not the case. I loved the production and we work very closely with Sally Wainwright, but we get as many people leaving here who haven’t heard of the film and saying they want to see it as we do people who came here because of it, so it works both ways.”

Wright is constantly impressing upon me the fact that the Brontë Society is a large organisation, with many members as well as its core management team. There will always be traditionalists, and there will always be modernisers, and while that might have prompted the clashes of the last couple of years, it may be that the ripples are finally smoothing out.

Despite her desire not to be seen as the saviour of the Brontë Society, some of the peace that’s been restored must be down to Wright. She says: “When I was working freelance, I swore I’d never take a full time job again. But then this came up.” She looks out of her window at the rolling hills and dry stone walls. “It’s a massive opportunity and a huge privilege. I mean, who wouldn’t want to work here?”

If the Brontë Society’s past troubles really were down to an ideological clash between traditionalists and modernisers, it seems that they might have found the perfect solution, because in appointing Kitty Wright as their executive director, they appear to have got both.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks