Crime writers who invent intricate and illegal plots are perfectly capable of becoming criminals

Tim Watson-Munro first went to prison when he was 25 – as a prison psychologist. Two decades later he was booted out of the profession for drug offences. In his new book, ‘Dancing with Demons’, he explains that really there is no such thing as the criminal mind any more than there are criminal classes: there is the potential for criminality in every single one of us

Normally people get arrested first and go to prison later. Tim Watson-Munro stands out to my mind, since he managed to go to prison first and then get arrested a decade or two later. Only Down Under perhaps, where the water in the bath goes down the plughole counter-clockwise and it’s winter when it should be summer and they use the word “rort” (sharp practice or scam or con) rather a lot.

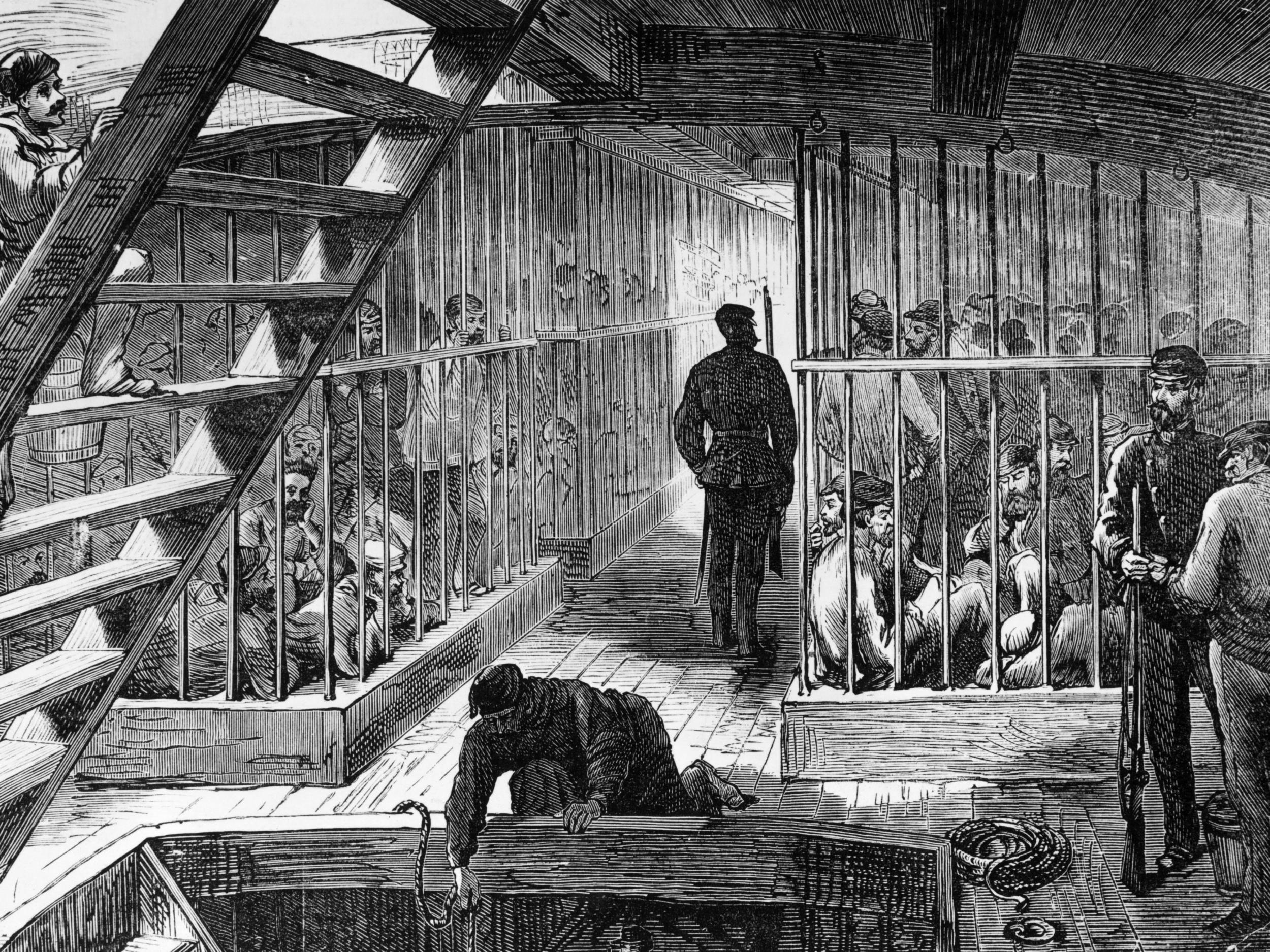

Captain Cook claimed possession of Australia in 1770 – mainly to out-manoeuvre the French and the Dutch (he admitted that where the Aboriginal inhabitants were concerned, “all they seemed to want was for us to be gone”). The first convicts stepped ashore in Botany Bay in 1778. The whole of Australia – such was the insight of our administrators – would serve as a vast far-flung prison colony for the “criminal classes” of Great Britain. And nearly 250 years later, the country still has its fair share of prisons and “crims”. The great bush ballad Waltzing Matilda, after all, tells the tale of a thief who would rather end up in a billabong than go to jail.

Tim Watson-Munro first set foot in the notoriously harsh Parramatta Gaol in August 1978. He was welcomed with enthusiasm by the inmates. “Nice look’n arse,” was one of the comments. “Can’t wait to get you into my cell, baby.” He was 25, not long graduated from Sydney University, and he was the new prison psychologist, working for the Department of Corrective Services, and he was wondering what the hell he had got himself into.

Jean Baudrillard, the French sociologist, maintained that there is something “innocent” about a country that contains a place called “Woolloomooloo” (which is real and is a suburb of Sydney). Be that as it may, the young and ill-prepared Tim – who had once been babysat in San Francisco by the granddaughter of Albert Einstein – was soon mingling with hardened murderers (both mass and serial), rapists, thieves, rogues of all stripes, and innumerable con-artists. In his richly entertaining new book, Dancing with Demons, he relates the tale of one con, Carl Synnerdahl, who managed to engineer his way out of jail by pretending, very successfully, over a number of years, and despite any amount of testing by sceptical ophthalmologists, to be blind. And was only ultimately caught out when he made the mistake of having a fling with a vicar’s wife and letting on about his secret during their pillow talk – and she duly grassed on him (the ultimate sin in the con’s rule book).

Fast-forward 20 years. Tim is a successful consultant on many a prominent criminal case. He is in demand by the media. He is on his second marriage, is the father of several children, guzzles a lot of vodka, cognac, and champagne, and is a cocaine addict. Then, in 2003, the police finally come for him. They had it in for him anyway, and put him under surveillance, since he managed to get a few dead-cert cases off the hook and was therefore officially asking for it. So perhaps he should have tried to keep clean. As it is, his regular supplier is arrested and starts “singing like a canary”. Tim goes down.

Which explains two things. One is that he is a deeply sympathetic figure, having fallen from grace. And, secondly, why probably the most poignant, even tragic case among all his clients is the figure of Alan Bond. “Bondy”, as he was known, was certainly Australia’s most high-profile and colourful business man of the seventies, eighties and early nineties, and could have been “one of the richest men on the planet” (as he argued, “if only…”). He struck deals with General Pinochet in Chile. He practically owned Perth, in Western Australia. He bought Van Gogh’s Irises for (then a world record) $54m (£33m) and became an all-Australian hero when he won the America’s Cup in 1983 with a new type of sail. Then it all went pear-shaped. He went bankrupt and was put on trial, in 1992, which is when he ended up in the hands of Tim Watson-Munro.

Tim diagnosed some measure of cognitive impairment following a heart operation and announced in court, to great effect (echoed in tabloid headlines around the world) that Bond, the great entrepreneur, was “not fit to run the corner store”.

“He was a good guy one-to-one,” Tim said when I spoke to him in Sydney (we met, appropriately enough, at the Justice and Police Museum just up from the Opera House). “But so driven. His whole identity related to his public achievements. So he over-reached.” The real tragedy of his life, Tim said, was that his second wife committed suicide, drowning in their swimming pool, after a depressive illness. “He never really recovered from that.” He finally died, a broken man and shadow of his former self, in 2015.

A spectacular rise, followed by hubris, followed by an equally spectacular and humbling fall: Bondy and Tim Watson-Munro have a lot in common. Tim, the analyst, has to undergo analysis. The criminal consultant ends up in court. But he has successfully reconstructed himself, however. He was struck off, banned from following his chosen profession, but has now been re-admitted to the hallowed halls of criminal psychologists, having personal as well as professional experience of what it means to be a criminal.

The great thing about someone like Tim is that he demonstrates that really there is no such thing as the “criminal mind” any more than there are “criminal classes”: there is a potential for criminality in every single one of us (some of the drug squad detectives that arrested him were themselves arrested – for drug dealing). And crime is not about to die out either. As the great sociologist Emile Durkheim pointed out, even in a society of saints the ratio of crime would remain pretty much the same because the standards would go up. And, despite having Woolloomooloo, Australia is still far from being a society of saints. Crime, Tim said, “is mainly a confluence of genes, upbringing, and – right now – ice.”

Cocaine is no longer the drug of choice for the new generation. “Ice”, or crystal methamphetamine, is creating “a new genre of criminality”. It accounts, Tim said, for 80 per cent of all crimes in Australia. It is cheap, widely available, and extremely dangerous. “It’s a libidinal drug,” Tim said. “It pushes your sex-drive through the roof and it completely disengages the super-ego” (our highly disciplinary Sergeant-Major, according to Freud). And it induces paranoia. “Ice is attacking the social fabric,” Tim said. “Kids as young as 13 take it at parties, then they go out with their mates, and so it happens.”

Tim paid his debt to society and then wrote a good book about it. “Mr Nice”, the former drugs maestro Howard Marks, was the same. Every now and then – one thinks inevitably of the case in Britain of Jeffrey Archer, bestselling author, and fraudster and jailbird – a writer becomes a criminal.

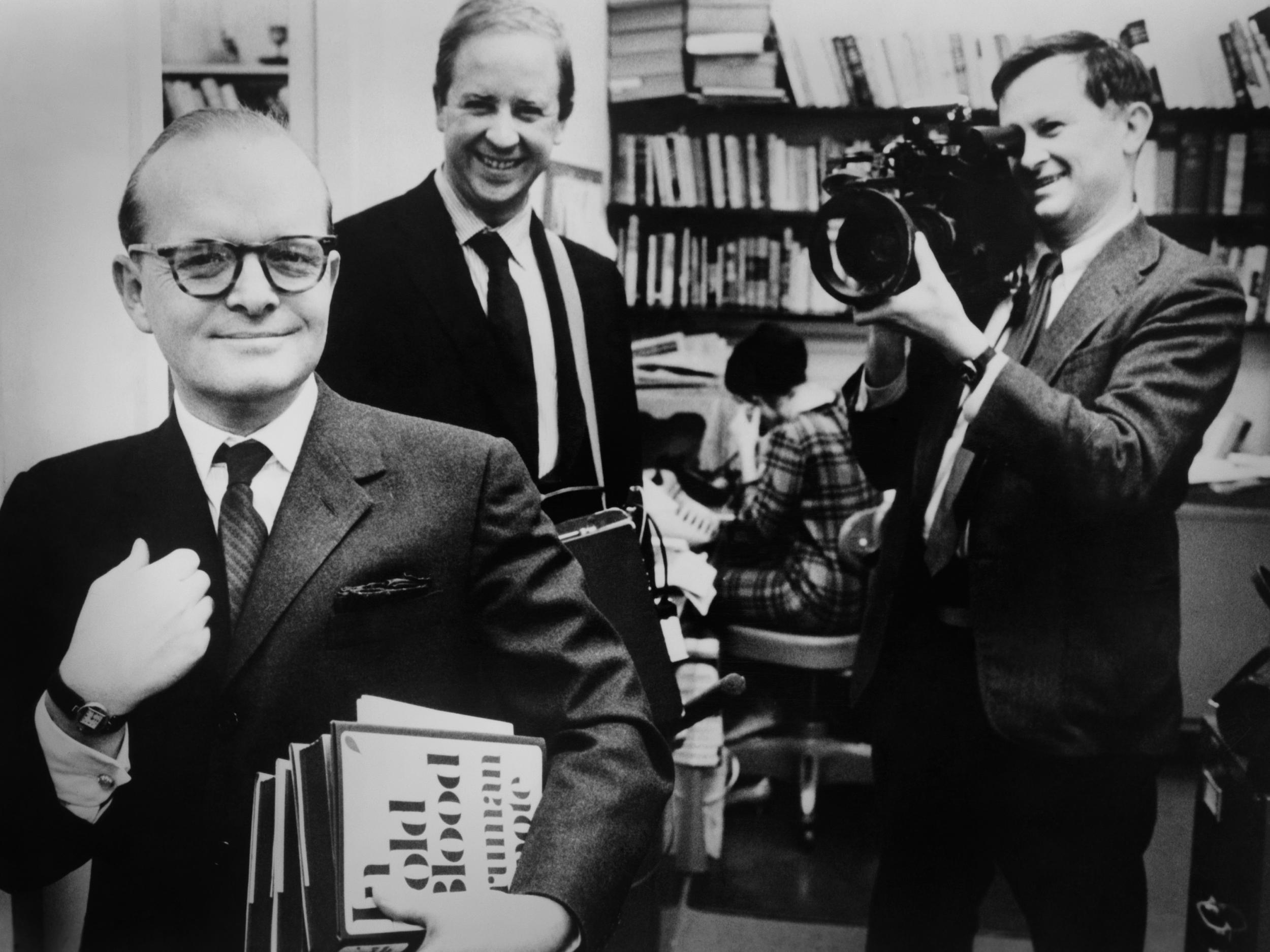

But either way there seems to be a natural affinity between writing and crime. Which may explain the explosion in the genre loosely known as “Crime”, ranging from True Crime stories (Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood is the best-known example), through to mysteries and thrillers. They are the lifeblood of today’s publishers. As one publisher recently said to me: “They’re the only thing that sells.” They are keeping everyone else afloat. So it is not surprising that Dr Beth Driscoll, at the University of Melbourne, has been given a big grant by the Australian Research Council to launch her own investigation into the literary and publishing phenomenon of crime under the heading of “Genre Worlds”.

“The number of works of crime fiction has more than tripled this century,” she said when I met her on the leafy, cloistered Melbourne campus. “And more than six times as many thrillers are being published.” In Australia she cites, in particular, the work of Helen Garner and, on television, the popular Underbelly series. Crime, broadly speaking, has been going down, while the literary and cultural phenomenon of “crime” has been going up.

It may be that crime fiction flourishes where true crime is in decline, expanding to fill the space available. And it could be that literary and filmic crime (which almost invariably shows heists, for example, going badly wrong – think of Reservoir Dogs, for example) is actually having a positive effect on the crime figures and deterring potential criminals from going down that road. This is the effect that specialists refer to as “apotropaic”, warding off evil spirits.

But there is one other sinister possibility. Self-evidently, writers who invent the most intricate and manifestly illegal plots are perfectly capable of becoming criminals. Presumably the smartest ones will never even be caught (and are even now up to no good somewhere in the world). Anyone who can concoct a plot is only one small step away from putting one into execution and out-witting detectives. Which may be why we revere thriller writers (from Christie and Chandler through to John le Carré and PD James). They are akin to Godfather figures (I speak of course of Marlon Brando and the original book by Mario Puzo). But there is also, it occurs to me, the potential for “reverse mimesis”.

Tim Watson-Munro says that the most popular reading among Australian cons is “Lee Child and Jeffery Deaver – and of course press articles about themselves. Toxic narcissism is rife.” They also watch Pulp Fiction and Goodfellas a lot. I’m not sure if Tarantino and Scorsese make crime more or less attractive. Maybe they make it clear that it’s inevitable. And the watching can lead to reading too, but, says Tim, “most cons have poor concentration skills arising from impoverished education and or drugs and alcohol.“

Now consider the case of the literate potential criminal. As per Tim Watson-Munro, this could be you. Literacy does not automatically inoculate you against evil. So you read a book about true or invented crime, some heinous plot to do with hoodwinking or doing away with a party or parties. And you think to yourself: You know what, I could do that. You become a perpetrator. And the latest offerings in popular fiction will provide you with the know-how to lead a life of crime. A blueprint or at least a rough guide. Our only hope is that our contemporary real-life detectives, the Morse and the Lewis of our day, are also reading them and working out equally ingenious ways of fighting back against all the new Professor Moriartys.

The other major growth area in contemporary publishing – as Beth Driscoll’s co-investigator in Genre Worlds, Dr Lisa Fletcher told me – is romance (witness, for example, Fifty Shades of Grey, if that is romance). The one-night stand or erotic romp doesn’t count, apparently. Romance has to be sustainable and it involves treating the significant other as “home”. Maybe they could try making more Mills & Boon novels available in Australian prisons. Or perhaps that could be considered cruel and unusual punishment.

I still recall the words of one long-term convict in Sing Sing in New York, where I had been teaching existentialism, who came up to me after class and quoted a line of Sartre’s back at me: “Hell is other people. I’ve been thinking that for the past 20 years or so.”

Dancing with Demons: True Life Misadventures of a Criminal Psychologist by Tim Tim Watson-Munro. Publised by Pan Macmillan Australia

Andy Martin is the author of Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me. He teaches at the University of Cambridge

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks