Sexual addiction: Is there really such a thing?

High-profile celebrities have come out as being ‘addicted to sex’, but is there really such a thing – or is it simply a good excuse for bad behaviour? Andy Martin investigates

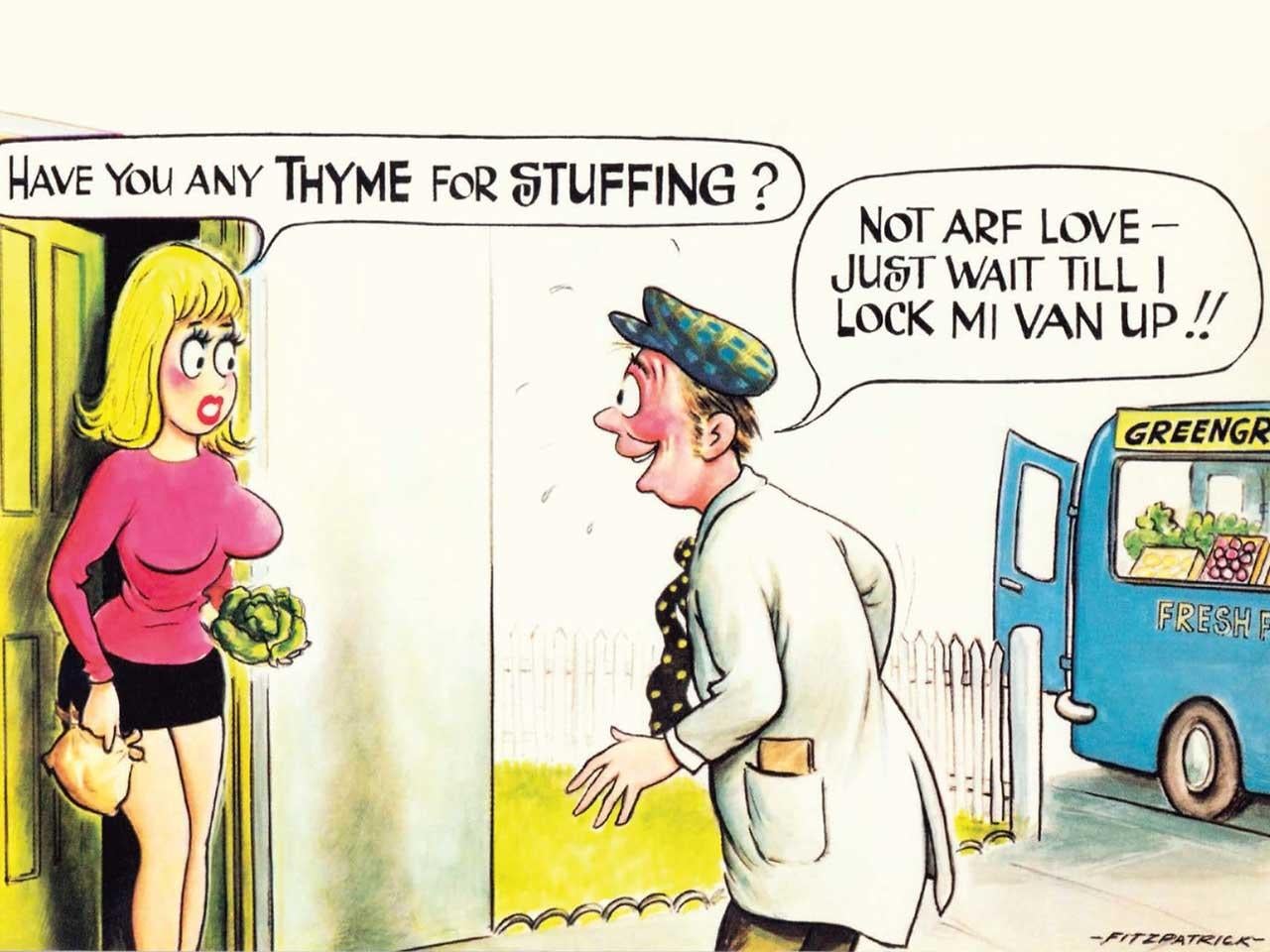

So Ozzy Osbourne has recently come out as a “sex addict”. Following on from episodes with drink and drugs, he is now in rehab on account of having OD’d on sex. To the tune of five starlets, according to his wife Sharon. Once upon a time all this would be known as being caught with your trousers down. In flagrante. In the classic era of dirty postcards, it was always the milkman or a salesman of some kind (encyclopaedias anyone? ), and the excuse was that they were “delivering” or “giving” someone something. Now the milkman, in this more enlightened age, discovered by an irate husband – or in this case wife – would presumably say, “I have a condition. I need treatment. Call rehab A&E”.

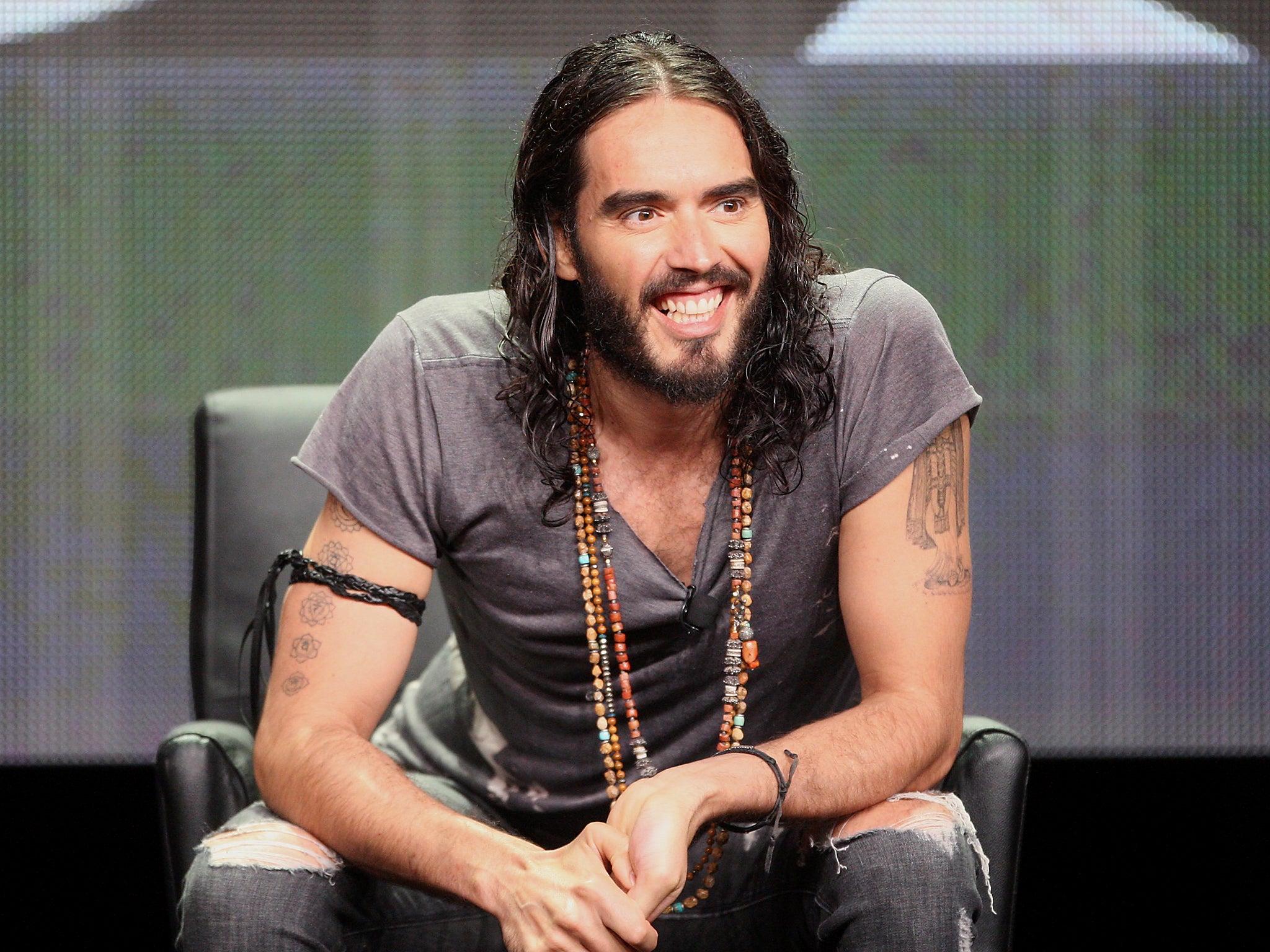

Osbourne thus joins a distinguished cast of addicts. For years, Russell Brand has ranted publicly about his various addictions, sexual and otherwise. According to one biography, at the last count, Hollywood star Warren Beatty is supposed to have had 12, 367 lovers. In a purely fictional way, Michael Fassbender was similarly exhausting in Shame, a gruelling movie that can stake a claim to being the least romantic film ever made. On the presidential side, so far as I know the Groper-in-Chief hasn’t yet come out, but Bill Clinton came fairly close with his “zipper problem” and JFK, retrospectively, qualified for treatment. He had a bad back, apparently, but a fairly bad front too. He is alleged to have said that he would get “a terrible headache” if he didn’t have at least one woman every three days, or possibly three women every day, if possible.

I was once invited to write a book about Kennedy. “I’ll have to mention the sex thing,” I said to the editor, a pleasant woman brimming with enthusiasm. “You know warts and all, otherwise no one will believe it.”

“Do you really have to have the warts?” said the editor. “Couldn’t you leave them out for a change?”

I was sorry to have to kiss goodbye to that job. She was offering me a shedload of money and instant access to the Kennedy archives and all I had to do was strike a positive note. Which I was willing to do. Just not all the bloody way through. Turned out the whole job was being funded by the Kennedy estate, fed up with too much negative publicity. They thought they could counteract the calumny with a hymn of praise. But one thing I feel I could now say in defence of Kennedy and the age of sixties optimism, before it all went pear-shaped, is that at least he never resorted to the addiction narrative. Although I guess the “headache” line is not a million miles away. Maybe (reverting to romantic mode) on account of heartache.

Legend has it that Raymond Chandler, the alcoholic writer and creator of Philip Marlowe, once wrote the first half of a film they had already started shooting and then he hit writer’s block. Doctors had told him he couldn’t drink again if he wanted to live; but he couldn’t write without a drink. So the studio set him up with a typewriter and a bottle and an ambulance waiting downstairs to rush him off to an instant drying-out clinic until the film was finished. With sexoholism it’s starlets lined up on the couch in place of the bottle.

I might as well come clean and admit it. I have an addiction. People who know me well will tell you this. I imagine there are already photographs on Instagram catching me in the act so I might as well come straight out with it. I’m an olive addict. Yep. Black or green, classy kalamata or just plain old co-op stuffed. I just can’t get enough of them. I get a headache if I don’t have them at least twice a day. So far I’ve managed not to have them on my cereal of a morning. But I’m already looking forward to my next fix and checking the larder. I suffer withdrawal symptoms if I don’t get more than my fair share. Unless, of course, on the other hand, I’m just indulging or even deluding myself.

A couple of other addicts spring to mind, now I come to think of it: Wordsworth (daffodils) and Popeye (spinach). We are all, I suspect, addicted. The thing we are addicted to is the addiction narrative and I think we need to get over it. We need to go cold turkey on the addiction concept. Which has bewitched us, cast a spell, or a curse. Maybe it’s not too late. Some of my best friends are addicts, one way or another. One writer I can think of reckons the next novel depends entirely on a constant supply of Camels and coffee. He doesn’t mention starlets. I don’t want to fatally weaken his highly caffeinated hero or put anyone out of a job or anything. But a whole industry has grown up around addiction.

Maybe I should go and have a word with sex therapist Paula Hall, who offers treatment for addiction at her London clinic. She speaks well and she writes well (and even has a TED talk on the subject). Maybe she can do something about the olives. I doubt it though. Because this is the thing about sex therapy: it presupposes that there really is an addiction that can be cured, that there is a “condition” that is susceptible to treatment. I imagine that the pharmaceutical industry has come up with a pill that can switch you off, as well as another pill that can switch you right back on again. In other words, their principal effect is not to fix anything, but rather to convince everyone that they are not responsible for their own behaviour. They are outsourcing willpower. And charging for the service.

Someone once asked me: “What do you think about Hegel, Marx and Freud?” I think I can now answer that daunting question about three heavyweight 19th century thinkers. They re-invented god or destiny in the shape of invisible “forces”, whether it’s history, production, or the unconscious. They are all variations on the master-slave narrative, in which the individual has become a slave to something, and everyone can (as Darth Vader would say) “feel the Force”.

The 20th century has helped to amplify and imprint this narrative in our heads. For a brief while I used to work at Ford in Dagenham. The rise of the assembly line, and by extension robotics generally, has contributed to our sense that we are “programmed”, or, like one of the products rolling off the end of the line, “driven”, that there is some unstoppable “mechanism” inside us against which it is useless to struggle. In this respect DNA, even if it helps to nail perpetrators, to some extent lets us off the hook. It was my DNA dun it, your honour. I’ve heard something like this at the Old Bailey. But there was a case in the United States where the murderer’s defence was that his brain made him to do it. Stout denial. The judge duly sent his brain down for life and told him he could choose whether to go with it or not.

It’s not me, it’s my “condition”. My “addiction”. The word itself has an interesting history. It comes from the Latin, addictionem (sounds like a Harry Potter spell of some kind). But it originally had nothing to do with sitting around smoking pot or watching online porn all day long. The infinitive, addicere meant “to deliver” (yes, just like the milkman in the dirty postcard), or “award” or “sacrifice”. So it implied nobility of action. But the notion of self-sacrifice assumed a different aspect in the 20th century, as if the self had been steamrollered by a “compulsion”, or need. In the history of addiction, it’s the “dicere” part of “addicere” that predominates, it’s all about the “saying”, the language of justification and excuse.

The notion of addiction does not appear in Shakespeare, although he may well have taken “compounds strange” (Jeff MacQuain’s Coined by Shakespeare notes that in Henry V the word means a relatively neutral “inclination”) And it doesn’t pop up once in the classic Confessions of an English Opium Eater either. Thomas de Quincey (writing in the early 19th century) didn’t think he was an addict. Neither did Sherlock Holmes, even if Dr Watson wasn’t too happy about it. At most it was a habit. But at some point we invested the notion of habit with some kind of rigidity and power over us. Now addiction has been industrialised and medicalised and reified. In the preamble to Narcotics Anonymous meetings, they don’t bother with a definition of addiction, they simply say: “We all know what it is, don’t we?” I’m not sure that we do, to be honest.

Albert Camus in his great essay, The Myth of Sisyphus, didn’t speak of sex addiction, he used the phrase “donjuanism”. At the end of his life he was writing love letters to at least four different women on three continents. He drove his wife up the wall of course, but he still had nothing on Georges Simenon, who boasted of having relations with at least 10, 000 different women (even though he must have lost count surely), which makes his autobiography a rather dull and repetitive affair. But the point that Camus makes is that this very repetition is an “absurd” gesture, maybe an attempt to inject some meaning into merely chaotic existence. In my absurdist sexonomics, there is always an asymmetry of demand and supply. Addiction is just demand gone mad.

Among women writers, Simone de Beauvoir, author of The Second Sex, must have some claim to being among the most prolific of sexual adventurers. She used to be a high school teacher but they sacked her when she kept on having affairs with her students and then passing them on to Jean-Paul Sartre. I guess now she would resort to the flaccid “addiction” alibi, but then, back in the 1940s, she bravely opted to say: “This is just what I choose to do. It was all my idea. The act is mine.”

My own hero among sexual experimenters of the 20th century is Brigitte Bardot. My best friend Griffo and I, both aged 15 at the time of our odyssey to St Tropez, were convinced that she had an addiction to 15-year old boys. That she was a sex addict, possibly with a side-order of bestiality, was the subtext of the story about her in her film-star days that she had a donkey, nicknamed “Romeo” stay in her hotel room in Spain (on a shoot with Sean Connery moreover). I remember that she caused consternation, particularly to me and Griffo, when she subsequently had another donkey castrated on her farm in Provence on account of his over-exuberance. A drastic form of what might now be known as “Sexit”. I’m not sure she gave the donkey a vote on the subject either.

I’m not advocating castration. Almost the opposite. But maybe we could consider cutting off our allegiance to and lazy dependency on the very idea of addiction. Now where are those olives?

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Reacher Said Nothing: Lee Child and the Making of Make Me’ (Bantam Press, RRP £18.99). He teaches at Cambridge University. Follow him @andymartinink

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks