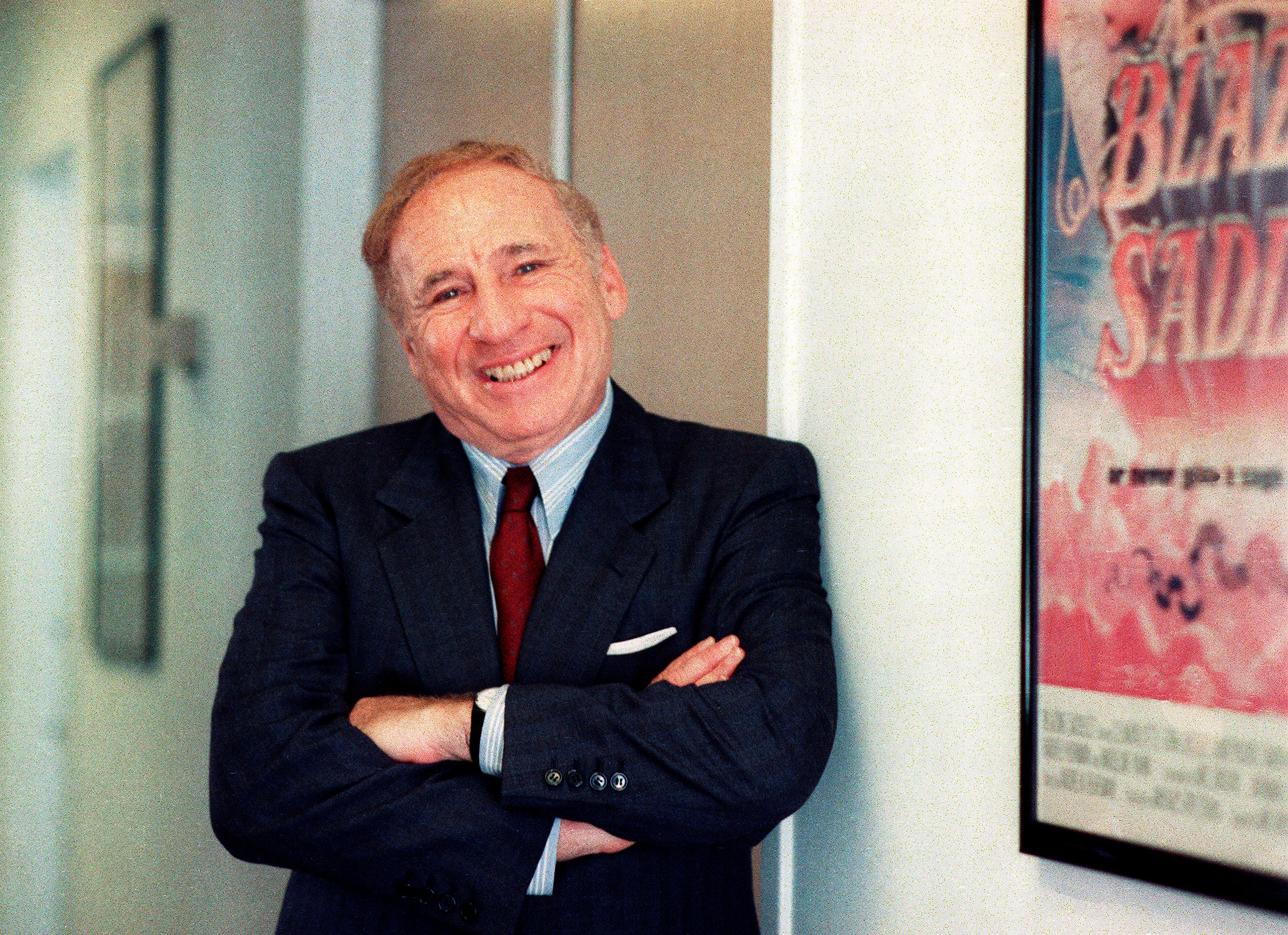

Q&A: Mel Brooks, 95, is still riffing

Leave it to Mel Brooks to blurb his own memoir

Leave it to Mel Brooks to blurb his own memoir.

There, along with laudatory quotes from Billy Crystal, Norman Lear, Conan O'Brien and others is one from “M. Brooks," who hails “All About Me!” as: "Not since the Bible have I read anything so powerful and poignant. And to boot — it’s a lot funnier!”

“All About Me!," which landed on bookshelves Tuesday, is indeed chock full of stories, anecdotes and memories from a comedy master of biblical proportions. Brooks, 95, spent much of the pandemic working on the book — a year of remembering everything from getting hit by a Tin Lizzie as an 8-year-old in Williamsburg Brooklyn to writing the musical version of “The Producers” with Tom Meehan at Madame Romaine de Lyon in Manhattan over omelets.

“Like everybody else, I’ve been mostly stuck at home and fed up with the same diet of information and food,” Brooks says. “Thank God I could let my mind roam free to remember.”

For the first time, Brooks has put down on paper all of his tales, from growing up in Depression-era Williamsburg ("I loved the Depression!" he says cheerfully), serving in the army during WWII, starting out in the Borscht Belt, writing on Sid Caesar's “Your Show of Shows,” launching his 2000 Year Old Man schtick with Carl Reiner, coming up with possibly the greatest comic conceit of all time ("The Producers"), and crafting the films “Blazing Saddles,” “Young Frankenstein,” “High Anxiety," among others. There are tender chapters on his wife Anne Bancroft, who died in 2005, and Reiner, who passed away last year. There are jokes and omelets.

In a long and lively phone interview from his home in Los Angeles, Brooks reflected on his the book and his life in show business — “the grandest adventure any human being could ever take,” he says. “Being in the theater and making movies is just a world of make believe. Fabulous."

AP: What prompted you to write a memoir?

BROOKS: My son Max said, “You know, Dad, you’re going to be stuck in the house for who knows how long. Why don’t you just write a memoir? Just tell them what you told me when I was growing up. You’ll have a big fat book.” He got me started. He got me a publisher. It was great. It saved me from going mad.

AP: The section on your childhood in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, is especially vividly and fondly recalled. You write that while many think a life in comedy springs from pain and a difficult childhood, for you...

BROOKS: I wanted to keep the party going. I wanted to keep the happiness and joy and explosions of laughter going into a dour part of our lives, not our childhood anymore. I was once interviewed and the guy said, “What was the happiest part of your life? Was it winning the Academy Award? Was it marrying Anne Bancroft?” I said no, not at all. It was my childhood. From about 4 or 5 or 9, it was the most exciting, happiest, joyous life that anyone could experience. The guy said, “What happened at 9?’ I said, “Homework.” I realized the world wanted something back. To this day, it’s still a bad thing. Homework is a bad thing. It takes away precious minutes from your childhood.

AP: Depending on laughs for happiness can lead to a lot of heartache. Was there any downside to needing that response?

BROOKS: Oh, yeah. When stuff didn’t work. When you worked so hard on an idea or a project and the audience just said: No, thank you. There was plenty of heartbreak right there. When you had a show on television like "Get Smart," it was dropped after the first year. ABC just said no second year. There’s ups and downs. I didn’t write a lot of the downs in the book. Why bring the reader down when there’s so many ups to talk about?

AP: You say that despite being a filmmaker and producer, you identify most as a writer. Was that always the case?

BROOKS: Yes, always. It always started with an idea, with a bunch of characters that interplayed. It was the most interesting thing I could do with my life. I was a good reader and a good reader is maybe the basis for becoming a good writer.

AP: What books were you reading?

BROOKS: When I was writing for “Your Show of Shows,” I met Mel Tolkin. His name was actually Shmuel Tolchinsky, he was a Russian émigré who came to Canada when he was 14. He was kind of a sage. He introduced me to people like Nikolai Gogol. So when I started writing, already the stakes were high. I wanted to write like Gogol. I wanted to write like Tolstoy. I wanted to write like those guys. I fell in love with Dickens. I was very lucky to run into Mel Tolkin. I learned that writing was not just writing. It could be miraculous. It could be wonderful. It could be really funny. I didn’t learn from a guy that just wrote jokes. I learned from a guy who learned from the masters.

AP: Years into the hallowed run with Sid Caesar, you implored him to join you in leaving television for the movies. You guys were then immensely popular. What drew you to film?

BROOKS: I knew. I was so ahead of my time. I said: Harold Lloyd is still hanging from the clock in “Safety Last! ” from 50 years and you do an hour and a half of incredible comedy that is gone the minute they turn off the TV set. It’s gone forever. He understood that, but he couldn’t turn down the offer they gave him. I understood. I said, “Well, I’m going to continue but I’m going to go into movies. You can do a lot more, you have a lot more time and they last. They’re around. Every movie I’ve ever made is still around, playing somewhere. Maybe TCM or some little art house in Des Moines, but it’s somewhere. It plays. A movie is forever.

AP: A kind of running gag in the book is the litany of film executives who give you notes that you gladly accept only to completely ignore.

BROOKS: (Laughs) I always agreed to them, 100%, to their faces. When (producer) Joseph Levine said, “Get rid of this guy Gene Wilder in ‘The Producers.’ Get rid of him. He’s funny looking. You can get a handsomer guy who has more star quality.” I said, “Yes. He’s out. You won’t see him again.” I never changed a thing. They forget. As soon as the money comes rolling in, they simply forget.

AP: Has what’s funny to you changed at all with age?

BROOKS: You never know what’s funny to you until it hits you, and then you say, “Gee, that’s funny!” Things that are positive surprises have always thrilled me. Like Bialystock and Bloom planning on having a flop and instead have an incredible hit. There’s a kind of crazy secret in my writing that I didn’t realize until I read the book myself. It seems that I know that in this world, it’s either love or money. They don’t both happen at the same time. I don’t know whether I learned it from Russian literature or Mel Tokin or life. But it’s money or love, and I go for love.

AP: Do you still think up 2,000 Year Old Man jokes?

BROOKS: Well, without Carl, who I loved so much and who was such a great, deep important part of my life, I don’t think very often of the 2,000 Year Old Man. Once in a while, I’ll think of something and think, too bad Carl isn’t alive and we could’ve nail that idea. But you meet people. You meet Carl Reiners and Tom Meehans and Anne Bancrofts. You meet people. And then you’re lucky if you have children that you like and like you. I’ve been lucky in many departments.

AP: Do you remember your last conversation with Reiner before his death last year?

BROOKS: Yeah. The day he died, I said, “Carl, you’re eating two hot dogs.” He said, 'They ain’t gonna bother me. I love hot dogs and hot dogs love me.” But it wasn’t true. By that night, the hot dogs had done him in. He lived a long, beautiful, loving, giving, happy life. I was so lucky he was my dearest friend.

AP: Do you wonder what he would have thought of the book?

BROOKS: I think he would have liked it. He probably would have said “Why did you stop there? There was a lot more you left out!” There was never enough for Carl. He just wanted more joy and more comedy.

AP: He had been your regular movie partner. Without Reiner, what are you watching?

BROOKS: I haven’t been watching too many movies. I watch a little television. We used to watch the game shows. Now that he’s gone, I don’t watch them anymore. I like old movies. I like Turner Classic. Sometimes I see my old movies there, and I’ll actually enjoy it. I’ll say “That was a good joke.” Like in “High Anxiety,” I get very excited when Barry Levinson stabs me — I’m playing Janet Leigh — with the rolled-up newspaper after opening the curtain. We’re of course mimicking “Psycho” at every shot. The one shot I couldn’t mimic was the knife and the blood. It was too gruesome. Then I discovered the newsprint of the newspaper would trickle down and look like the blood. I got a poke in the ribs from Hitchcock when he saw it.

AP: A 19-year-old Dave Chapelle made his film debut in your “Robin Hood: Men in Tights.” What did you see in him?

BROOKS: There were about six, seven kids who came to audition. The minute he began reading, I said, "That’s the kid — the skinny little kid.” His rhythm was so perfect.

AP: Some comedians — including Chapelle, whose jokes about transgender people in his last stand-up special prompted a backlash — have lamented that today's audiences are too sensitive. As someone who often pushed boundaries of what was acceptable, what do you make of these cultural battles in comedy?

BROOKS: You’ve got to be careful. When things stir up people to great emotion, I stay out of that. I’m very careful and stay out of those. I don’t ever take sides because everybody’s right. The people who make fun of something that should not be fun of are right. And the people who are hurt because they’re trashing something that’s so important to them, they’re right. They’re all right. Stay back. Stay away.

AP: But you also weren't timid about subjects some considered off limits like mocking Hitler and the Nazis in “The Producers” or the language of “Blazing Saddles.”

BROOKS: I was lucky. I was politically incorrect and I didn’t know it. I didn’t know it, so I did a lot of great stuff. Then it became politically incorrect, like the N-word in “Blazing Saddles.” Richard Pryor was writing it with me. He just loved using the N-word because it was all true — the bad guys used it against Blacks. We didn’t think anything was wrong until later. You’ve got to say maybe it was used too much. Anyway, we were kids and it worked. It worked when it worked. I don’t think I could do those scenes in “Blazing Saddles” today. I don’t think I could get away with it. I think I’d offend too many people.

AP: Do you think about your legacy at all?

BROOKS: Oh, I don’t think about that. I just think: Buy another book.

AP: Many might say you played a massive role in bringing Jewish culture and comedy into the mainstream.

BROOKS: A lot of what’s described as Jewish comedy is really New York the drumbeat of New York, the struggle of the immigrants who made New York one of the greatest cities in the world. It’s New York comedy, it’s street-corner comedy. Seeing the world from a street corner in Brooklyn and making pronuciamentos that are always correct — that are crazy but always right.

AP: What inspired you to help make a part two of “History of the World,” as a Hulu series?

BROOKS: I’m working on that with Wanda Sykes and Nick Kroll and having a lot of fun. They came up with the idea and I said, “Fine, count me in.” There’s a lot of history we haven’t covered. There’s always history. You come up with ideas. The other day, I came up with the idea that you hear a lot of whistling wind and the screen gets darker and darker. And then a big announcement: “The Dust Bowl.” And then: “Hey, where are you?” “I’m over by the fence!” “I can’t see the fence!”

AP: In a great 1980s sketch, you created a coin-operated gravestone for yourself that played a videotaped message that began: "I was Mel Brooks, one of the funniest little Jews to walk the Earth.” Do you think much about death?

BROOKS: No. I gave up after 60 thinking about it because if I did, I’d be thinking about it all the time. So I don’t think about it much. When and if it happens it’s going to be a sad day — for everybody but me. (Laughs) I enjoy living. I’d like to do it as long as I can.

___

Follow AP Film Writer Jake Coyle on Twitter at: http://twitter.com/jakecoyleAP

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks