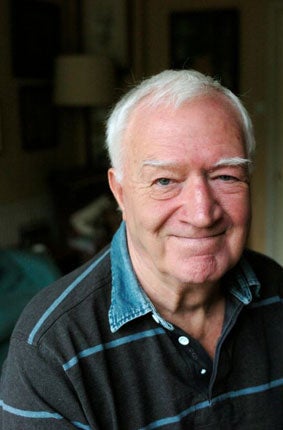

Adrian Mitchell: Poet and playwright whose work was driven by his pacifist politics

'Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people" may well be the most widely quoted observation of the last half-century regarding poetry in Britain. It was Adrian Mitchell's preface to Poems (1964), his first major collection. By the time of Mitchell's death last weekend, more Brits were relishing masses more poetry, because so much more poetry has got involved with so many more people.

This has happened in huge measure due to the non-stop commitment of Mitchell himself to reversing the situation he found so demoralising at the outset of his vocational path. His ground-breaking work as a political and performance poet, songwriter and playwright dedicated to the creative potential of all children and adults will live just as surely, and for just as long, as that of the forebears and contemporaries whose examples he frequently drew on. These include Shakespeare, Burns, Whitman, Lear, Carroll, Owen, Auden, Brecht, Beckett, Kenneth Patchen, Allen Ginsberg, Joan Littlewood, Lennon and McCartney, the (black) blues greats, and above all William Blake.

Mitchell's mother Kathleen was a Fabian socialist nursery school teacher who "encouraged me to argue", having lost two of her brothers in the First World War. In "My Father's Hand", Adrian recalls how his father Jock, a research chemist, had also suffered the desolation of the trenches, "Sent, by the King, to hell in a kilt". Many of Mitchell's poems, songs and plays explore and illuminate the extremes of innocence and experience in childhood, etching, shading and colouring in the lines between his own and those of others.

He was badly bullied every day at a prep school in Somerset during the Second World War, and was still pretty traumatised remembering it 65 years later: "I went home one day and said, 'I am not going back, I'd rather be dead'. My mother said, 'Is it the maths?' I said, 'No, it's the torture'. I was getting death threats, and told her what had been happening – but not everything, because when you are a victim you feel ashamed". Hence his lifelong non-violent opposition to violence, and poems like "My Mother and Father or Why I Began to Hate War" and "Back in the Playground Blues" ("Heard a deep voice talking, it had that iceberg sound: / It prepares them for Life – but I have never found/Any place in my life that's worse than the killing ground.")

After National Service in the RAF, which reinforced his pacifism, and Oxford, where he edited Isis magazine, Mitchell worked as a journalist from 1955 to the mid-1960s, since when his freelance writing and performances went from strength to strength. He wrote four novels – If You See Me Comin' (1962), The Bodyguard (1970), Wartime (1973) and Man Friday (1975) – some 50 volumes of poetry, and around twice that number of plays and adaptations for stage and TV. In the early 1960s he befriended the actor Celia Hewitt, who soon became the prime personal mover of his remaining 47 years. His collaborations on Peter Brook's multimedic Royal Shakespeare Company productions of Marat/Sade (1964) and US (1966), were seminal both for his subsequent theatrical efflorescence, and for the further evolution of radical-cultural activism worldwide.

US exposed the way sex gets converted into racist carnage by the war machine: witness this chorus from one of Mitchell's lyrics: "I had a dream about going / With Ho Chi Minh/But I'll only be crowing / When I'm zapping Pekin / I'll be spreading my jelly / With a happy song/Cos I'm screwing all Asia / When I'm zapping the Cong". The show was a clear case of grassroots agit-prop that worked. Mitchell observed how "People with short memories wonder why British artists ever imagined they could have any influence on the Vietnam war. At that time there was pressure from the US as well as from intellectuals like Amis and Levin for British troops to be sent to fight alongside the Americans. If the British anti-war movement did nothing else, it squashed that one flat."

Of his more than 30 works for the theatre, Pied Piper ran for three years at the National Theatre, while his adaptation of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was a much-loved production at the RSC. Another successful adaptation was Gogol's The Government Inspector at the National, and he also wrote songs for Peter Hall's version of Orwell's Animal Farm.

Along with his friends Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Andrei Voznesensky, Christopher Logue and the Liverpool poets, and the transatlantic beats and rockers, Mitchell functioned as arch-forerunner and pace-setter to the restoration of voice, body, music and heart to verse in our time.

One of his most constantly resonant moments will probably remain his cathartic renditions at the first Poetry Internationale at Royal Albert Hall in 1965, some of whose highlights were captured for posterity in Peter Whitehead's film Wholly Communion. Adrian's spot was shorter than any of the 18 others that evening, but (with the possible exception of Ernst Jandl's sound-poems and Ginsberg's finale) elicited the most concerted fellow feeling from around 7,500 auditors. One of his poems, "You Get Used To It" was an implacable cry against murderous racism "in hell or Alabama". The other, "To Whom It May Concern", with its nursery-rhymey counting-out refrain, was to become an anthem for the continuing "Stop the War" movements: "You put your bombers in, you put your conscience out, / You take the human being and you twist it all about / So scrub my skin with women / Chain my tongue with whisky / Stuff my nose with garlic / Coat my eyes with butter / Fill my ears with silver / Stick my legs with plaster / Tell me lies about Vietnam."

It was a classic demonstration of the then new voices' reinvention, as Mitchell put it, of poetry as what "We do together" – meaning with our fellow poets and, equally, our diverse audiences. He was probably the British poet I most often featured in the thousands of Live New Departures, Jazz Poetry SuperJam and Poetry Olympics gigs between 1959 and this year, and it came naturally to publish his texts in nearly every issue of my New Departures series and give him pride of place amid the 64 younger bards I anthologised in Children of Albion: Poetry of the Underground in Britain (1969).

He was characteristically prescient in an interview quoted in the "Afterwords" to that book, railing against British military conscription because our boys are "going to have to fight a white man's war, which is what this whole [Vietnam] thing is. And it's leading up to a global white man's war, eventually – maybe 20, 30 years away if we're lucky."

Again, his adaptation of Lope de Vega's Fuente Ovejuna (1989) set out to raise the still all too fatally under-examined problem that "When people's backs are rubbished against the wall, some of them are going to take up arms; when children are being starved or murdered, wives being raped, husbands jailed and tortured for speaking out, they're liable not only to kill in turn, but can get infected and enjoy nothing better than taking the most bloodthirsty revenge."

At a 1967 "Legalise Pot" rally in Hyde Park he read a poetic oration (also quoted in Children of Albion) of a kind he was to develop more and more charismatically, inflected like his musical stage play Tyger (1971) and TV play Glad Day (1979) with his signature neo-Blakean cadences: "These flowers are for love. / Good. That seems to be what we're alive for. / But is it a vague gas of love which evaporates before it touches another human being / Or is it a love that works? / A love so strong that it can free / A prisoner in Spain or Russia? / A love so bright that it can illuminate forever / The hideous darkness of the African sky? / A love so loud that it can shout BE FREE / To the imprisoned states of South America? . . . Or is it so small a love / That it has no more chance of changing the world / Than a poppy seed planted under the concrete floor / Of a nuclear power station? // It must become a love huge enough / To tear down all the offices / Where poverty, hunger, imprisonment and war are planned. / It must become a love intelligent and vast enough / To build Jerusalem, a million Jerusalems, / A world more loving / Than our most astonishing visions."

His Love Songs of World War Three (1989) synthesise poetry, drama, song and political protest at as high a level as that of any comparable collection I have read. He sees the Third World War as having begun in August 1945 with the gratuitous atom-bomb demolitions of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, when Harry Truman knew full well that Japan had been suing for surrender months before. Admittedly many of the lyrics make such volumes resemble hymn books, only fully fulfilled when they are heard and chanted, as his Little Richard update exemplifies: "You so draggy Ms Maggie / You tore this land apart / With your smile like a laser / And your iceberg heart / You taught the old and jobless / What poverty means / You sent the young men killing Irish and Argentines." But, as in every one of his books, there are gentler and more multiply communicative pieces, such as "For My Son", that reward many silent readings, too.

With hard-won but unfailing stamina, Adrian was giving himself to audiences at each event with ever greater intensity the older he got. And he also got more and more turned on and delighted by turning on and delighting children in particular into both writing and performing verse, songs and drama – their own as well as their elders', though not necessarily betters. I know of no other author (though perhaps some will now be considering it?) who forbade any use of any of their writings to be included in any way in examinations or tests: "I think that tests and exams dominate education and squash it. They're an educational experiment that has failed dismally".

Mitchell frequently celebrated his blood family as well as his extended ones, affirming his sense of kinship with nature and all sentient beings in poem after poem: "Long live the Elephants and Sea Horses / the Humming-Birds and the Gorillas / the Dogs and the Cats and Field-Mice / all the surviving Animals / our innocent sisters and brothers // Long live the Earth, deeper than all our thinking // we have done enough killing // Long live the Man / Long live the Woman / Who use both courage and compassion / Long live their Children".

Adrian Mitchell wrote his last poem, "My Literary Career So Far", the day before he died, and it will cheer up anyone who visits his publisher's website, bloodaxebooks.com – it was intended as a Christmas gift for all the friends, family and animals he loved, and was post-scripted "Merry Crambo and a Hippy New Year with love (I can't write letters and it's hard to phone as I recover from two months in Pneumonia, so take this new riff with a glass of good wine and drink to Peace in 2009)".

Three more books will be published next year: his final collection of poems, Tell Me Lies: Poems 2005-2008; his collected poems for children Umpteen Poems; and Shapeshifters, his versions of Ovid's Metamorphoses.

May his soul rest in the infinite peace he spent so much expensive energy spreading around. May his many works go on forever strengthening the resolve and achievements of those who, in Blake's words, work continuously for the rebirth of wonder and the enduring transcendence of Mental over Corporeal War.

Michael Horovitz

Adrian Mitchell, poet, novelist, playwright, songwriter and journalist: born London 24 October 1932; married firstly Daphne Bush (two sons, one daughter), secondly Celia Hewitt (two daughters); died London 20 December 2008.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks