Trunk calling: How conservationist Daphne Sheldrick became the Kenyan elephant's best friend

As one of the last daughters of the empire in a country dogged by violence, her dedication to orphaned elephants became one of the finer legacies of the British colonial presence in Kenya

Lying on the ground with a badly broken leg, having been tossed in the air by an elephant, Dame Daphne Sheldrick might have been terrified. But the conservationist, who has died aged 83, was born and raised in Kenya and had already survived many close encounters that would leave a lesser person gibbering.

As a child on camping trips, she woke to the sound of lions licking her tent. However, animals were not the only threat. Kenya was at the time a British colony.

During the Mau Mau uprising of the 1950s, white families were fair game to the rebels thanks in no small part to the brutal nature of colonial rule. (In 2011 William Hague expressed “sincere regret” for the thousands who had been detained and tortured.) When Sheldrick was nine months pregnant she survived an ambush by Mau Mau fighters.

So when a wild elephant she had mistaken for one of her hand-reared orphans turned on her in 1994, she took it in her stride.

“I opened my eyes. I could feel the elephant gently insert her tusks between my body and the rocks,” she wrote in her autobiography, Love, Life and Elephants: An African Love Story, in 2012.

“Rather than a desire to kill, I realised that the elephant was actually trying to help me,” she added. “I knew then and there that I had an absolute duty to pass on my intimate knowledge and understanding of Africa’s wild animals and my belonging to Kenya.”

Born Daphne Marjorie Jenkins, Sheldrick came from a family of settlers who left rural Scotland for Africa in the mid-1820s. Her great-uncle Will, a successful farmer in South Africa, began the family’s connection with Kenya after meeting governor Sir Charles Eliot. Eliot was offering free land to families prepared to move to his new colony. Among the families that subsequently boarded the boat to Mombasa were Daphne Sheldrick’s great-grandparents.

The settlers arrived to an uncertain future in a country with none of the comforts of home. They could not move their livestock inland without first swathing them in cloth to foil the tsetse fly. The new railway was notorious for the number of workers eaten by lions during its construction. And the 5,000 acres of virgin bush gifted by the British government were in fact already home to the Masai. After an arduous four-month journey to get there, Sheldrick’s family had to move on again.

I knew then and there that I had an absolute duty to pass on my intimate knowledge and understanding of Africa’s wild animals and my belonging to Kenya

By the time Sheldrick was born, third of Bryan and Marjorie Jenkin’s four children, the family was established on a farm in Gilgil in the Great Rift Valley. Marjorie Jenkins was determined to instil in her children a love for the natural world. Family walks included not just the farm dogs but an impala, a waterbuck and Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, a brown-furred dwarf mongoose. At the age of four, Sheldrick was given responsibility for the care of an orphaned infant bushbuck.

It was an idyllic upbringing but it was hard to run a European farm among African predators such as lions and leopards. At the same time, the global picture was changing rapidly. With the Second World War reaching Ethiopia, the British government looked to Kenya to feed the troops. Bryan Jenkins was tasked with shooting thousands of wildebeest and zebra in the Southern Game Reserve. He set up a portable biltong factory, assisted by two Italian prisoners of war. It was while camping nearby that six-year-old Sheldrick was woken by lions. Attracted by the smell of meat, they stayed to lick salt from the tarpaulins.

As soon as she was old enough, Sheldrick, who could speak Swahili, was sent to boarding school. She was a keen student, graduating eighth in her year and winning a university bursary. However, she was already in love with Bill Woodley, a student from her brother’s school, and chose instead to leave full-time education to be with him.

At around the same time, a state of emergency was declared in Kenya after Mau Mau guerrilla fighters, drawn from the Kikuyu, Meru, Embu, Kamba and Masai people, rose up against white colonial rule. The insurgency was put down with shocking brutality by British colonial officials and Kenyan “home guards”. Thousands of civilians were rounded up in mass detention camps and subjected to beatings, sexual assault and even castration, allegedly sanctioned at the highest level. (Finally, in 2013, after a long legal campaign, the British government apologised.)

Mau Mau retaliation was equally bloody and Sheldrick’s family did not escape the violence. During a Mau Mau raid on her great-aunt’s farm, five people, including three children, were burned alive. Sheldrick’s grandparents were beaten and left for dead in an alleged Mau Mau robbery. Meanwhile, a worker on the Jenkins’ farm wasted away and died, convinced he was cursed after refusing to kill his employers at the Mau Mau’s behest.

In the midst of this unrest, Sheldrick married Woodley, visiting the United Kingdom for the first time on their honeymoon. After their marriage they moved to Tsavo National Park, where they worked as wardens. In January 1955, Bill took the now heavily pregnant Sheldrick back to visit her family in Gilgil. Returning in darkness, they were ambushed. “A terrifyingly loud sound erupted and in the arc of the headlamps we could see crazed, menacing figures, clad in skins, coming towards us in a great swirl of anger and noise. Some were wielding pangas, some were hurling enormous boulders and others were firing at us from point blank range.”

Bill Woodley saved his wife and unborn daughter, Jill, by driving straight through the Mau Mau attackers. A year later, the capture of Mau Mau leader Dedan Kimathi marked the official end of the “Emergency”, but the rebellion continued underground for almost a decade.

The Woodleys survived the ambush but soon after their marriage foundered. Sheldrick, still Mrs Woodley as she then was, had fallen hopelessly in love with her husband’s boss with whom she had much in common. David Sheldrick was a keen naturalist dedicated to ending poaching. During his anti-poaching campaign, more than 25,700lbs of ivory was recovered and in 1959 and he was duly awarded an MBE. Meanwhile, Bill Woodley’s passion for hunting, so much at odds with his role as warden, was beginning to grate. Sheldrick left him for his high-minded superior.

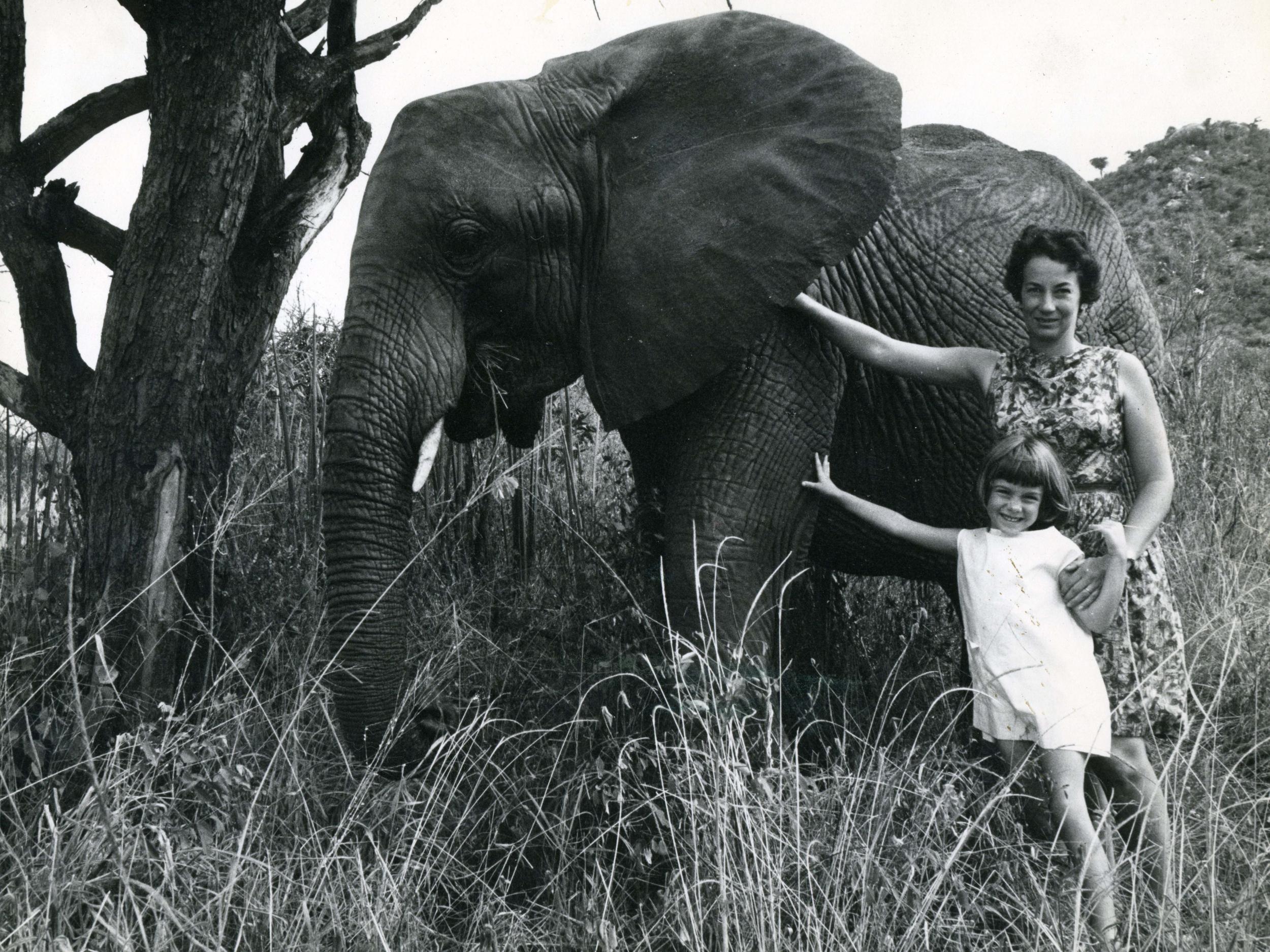

Sheldrick married David in 1960. Their family quickly expanded to encompass a variety of furry and feathered orphans, such as Gregory Peck, a buffalo weaver-bird, and Old Spice, a civet cat with a passion for the aftershave that bore his name. Soon after came a human daughter, Angela.

We had come to Kenya as children of pioneering families who had lived through difficult times as their parents struggled to farm the land, and when grown had served Britain with distinction in its world wars

David Sheldrick had already raised two orphaned elephants, Samson and Fatuma. His observations of the pair formed some of the first studies on elephant diet and migration. Daphne Sheldrick took charge of further orphans including one she named Aisha. In an interview, Sheldrick explained: “She came to us as one of the smallest elephants I had ever seen, with soft fuzz and ears as soft and pink as petals. When she arrived, my heart plummeted as we had never been able to save an elephant this young.”

The Sheldricks had already discovered that elephants do not thrive on traditional baby formula and after a few days on glucose and watered down cow’s milk, Aisha was wasting away. As a last resort, Sheldrick tried coconut oil. It worked. Aisha began to thrive on Sheldrick’s recipe and the future of many more orphaned elephants was assured.

By the early Sixties, the Mau Mau Uprising may have been over but the “winds of change”, as referenced in Harold Macmillan’s 1960 speech in South Africa, were blowing across the continent. When it came to Kenya, the British government decided that continuing colonial rule required more force than they were prepared to expend and Kenya was granted independence in 1963. The Duke of Edinburgh presided over the handover to Jomo Kenyatta.

They suffer loss and heartbreak on an almost daily basis, they grieve and mourn the loss of loved ones just as deeply as us, but they turn the page to focus on the living, and I try to emulate that

The change of rule caused much anguish for the white settler families, who, as Sheldrick described, “had come to Kenya as children of pioneering families who had lived through difficult times as their parents struggled to farm the land, and when grown had served Britain with distinction in its world wars. Britain began to turn its back on those people – even the daily BBC programme previously announced as ‘Home News from Britain’ became ‘News From Britain’, a subtle change that did not go unnoticed.”

Sheldrick’s husband was among those who struggled to renew his British passport at the time. David Sheldrick put the situation succinctly: “There was no question about me not being British when the Second World War broke out and I was called up to fight for your bloody country.”

The Sheldricks worried that the transition to independence would adversely affect Kenya’s national parks but it was their success in making the park a safe haven for elephants that caused the next problem. The elephant numbers at Tsavo had grown dramatically – from an estimated 5,000 to 15,000 – and the increased competition for food led to the devastation of much of the forest landscape. However, David Sheldrick firmly resisted the idea of an artificial cull and, in time, the more open grasslands created by the elephants’ indiscriminate browsing attracted new species, including antelope and buffalo. The Tsavo lions thrived.

Money, corruption, greed and ignorance motivates the evil ivory and rhino horn trade

In 1976, the parks were finally brought under government control, merging with the Government Game Department. Sheldrick explained that for the park’s “wild inhabitants, especially rhinos and elephants, who became instant targets, it was the death knell”. Shortly afterwards, David Sheldrick was offered a desk job in Nairobi and the family left Tsavo to an uncertain fate.

David Sheldrick died that same year. After his death, devastated Sheldrick began to raise funds in his memory to continue the work that meant so much to him.

The first official fundraiser was a film by former warden Simon Trevor. Somali gangs, armed with AK47s, had been gunning down entire Tsavo elephant herds, turning the park into a no-go zone. Trevor’s film on the crisis, Bloody Ivory, came to the attention of President Arap Moi, who agreed to attend the premiere. Alas, Moi was a no-show, but a few months later the Vatican proposed a papal visit to Kenya, during which the pope wished to bless an elephant and a rhino calf. Sheldrick obliged. The logistics were difficult but the publicity was priceless.

In 1987, the David Sheldrick Memorial appeal became The David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (DSWT), with a mission statement declaring it “embraces all measures that compliment the conservation, preservation and protection of wildlife”. Over the next 30 years the trust expanded to three sites: the elephant nursery at Sheldrick’s home in Nairobi, and two centres in Tsavo where the orphans were reintroduced into the wild.

There was no shortage of infant elephants to be reared. Though President Moi tried to signal an end to the ivory trade by publicly burning Kenya’s stockpile in 1989, the international appetite for ivory remained undiminished. Between 2003 and 2013, the DSWT saw a 500 per cent increase in the number of orphans rescued, driven by demand for ivory from China. In an interview in 2016, Sheldrick lamented that elephants were being killed at a rate of 50 a day, telling Bohotraveller: “Money, corruption, greed and ignorance motivates the evil ivory and rhino horn trade.”

Sheldrick spread the word about the crisis facing the elephants with numerous television appearances. She published four books, including her autobiography. Meanwhile, her work was recognised all over the world. In 1989, she was appointed MBE. She was awarded an honorary doctorate in veterinary medicine by Glasgow University. In 2001, the Kenyan government awarded her the Moran of the Burning Spear and in 2006 Sheldrick became a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, “for services to the conservation of wildlife, especially elephants, and to the local community in Kenya”. Her knighthood was the first to be awarded in Kenya since the country’s independence in 1963, something that Sheldrick said “left me dumbfounded but nevertheless extremely proud”.

At the time of Sheldrick’s death in April 2018, the DSWT hand-reared more than 200 orphaned elephants, more than 100 of whom were successfully released into the wild. As the trust approached its 40th anniversary last year, Sheldrick told Eluxe magazine: “I have always turned to the elephants for inspiration in the face of adversity. They suffer loss and heartbreak on an almost daily basis, they grieve and mourn the loss of loved ones just as deeply as us, but they turn the page to focus on the living, and I try to emulate that.”

As Sheldrick wrote in her autobiography: “Elephants are, indeed, just like us, and in many ways better.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks