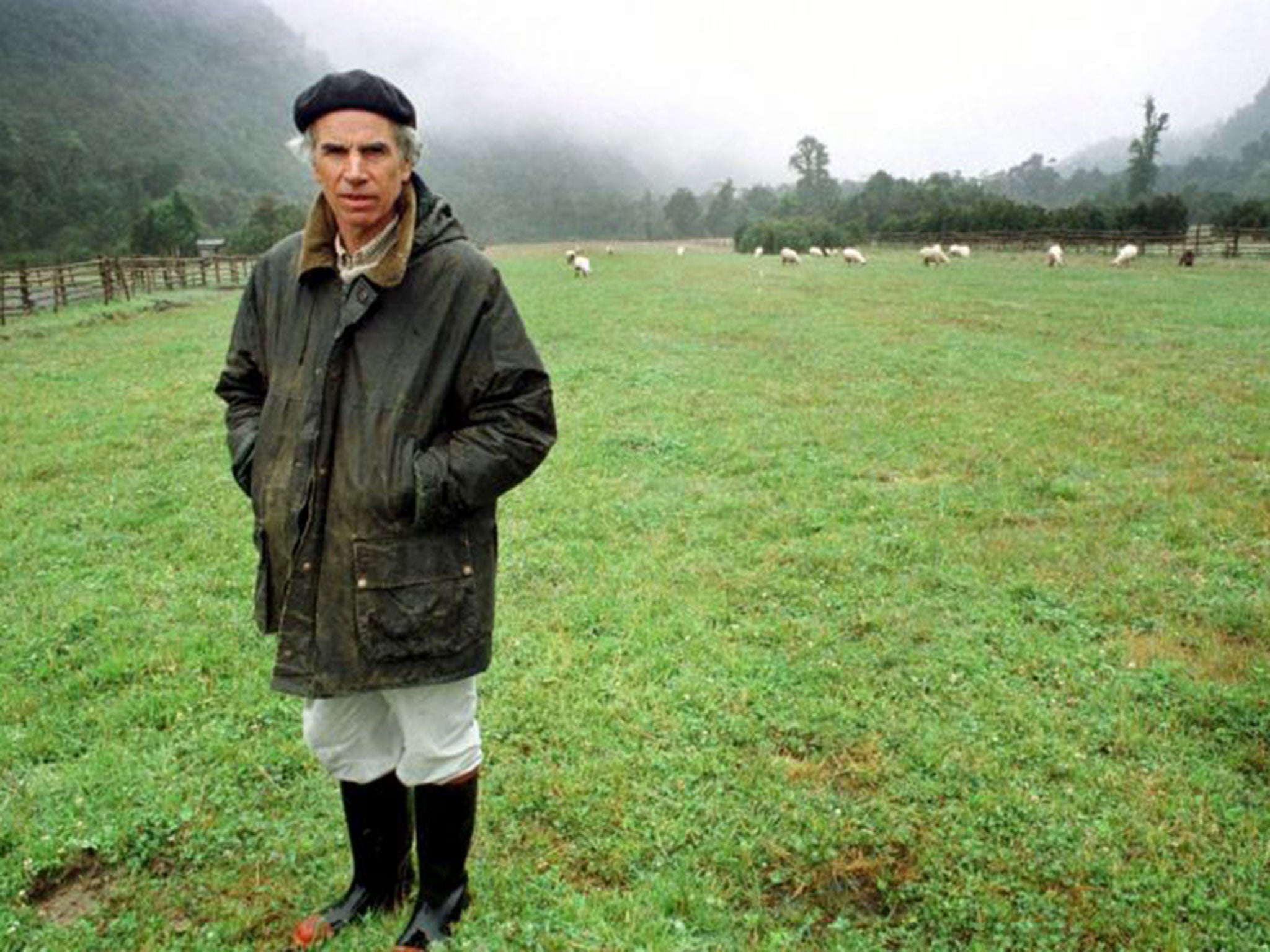

Douglas Tompkins: The man who turned his fortune into creating an ecological paradise in South America

He sold his business stakes, saying that he wanted ‘to stop selling people things they don’t need’

Douglas Tompkins was the multi-millionaire co-creator of The North Face, one of the largest outdoor clothing brands in the world, and of Esprit, the women’s fashion brand. In later life he eschewed consumerism, leaving the US to live and work in Chile as a conservationist on his own nature reserve.

Tompkins was born in Conneaut, Ohio in 1943 and grew up in New York. He dropped out of high school and travelled west in search of adventure, and in 1963 met Susie Buell, when he was hitch-hiking at Lake Tahoe in California. They married later that year.

Three years later, inspired by a hiking trip on Eagle Mountain in Minnesota, Tompkins established The North Face. He set up a shop selling outdoor clothing and mountaineering gear and opened its doors to the sound of the Grateful Dead playing live. “Doug saw the future,” said one former employee, Jack Gilbert. “The original store in North Beach, San Francisco, was old barn wood and green carpet, ahead of its time.”

But only two years later Tompkins and Buell had become bored with running a shop and sold the company for $50,000. Buell established a small clothing business, the Plain Jane dress company, with her friend Jane Tise in 1968. “We just started it, we didn’t really have a mission,” Buell recalled. “I’d been to Europe. I’d seen the fashion in Europe and France, and I just loved it, and it was something that was really missing here. Women in my generation didn’t have this free-spirited expression of themselves in their fashion like Europeans do.”

Tompkins brought investment and creativity into the business and helped in the company’s 1979 rebranding as “Esprit de Corp”, offering a collection of bright-printed casual clothes for younger women. By 1986 Esprit was turning over US $800m annually.

But the high was not to last. Disagreements over the company’s commercial and creative direction, together with marital difficulties, meant that the partnership in business, as in marriage, had to come to an end. The couple divorced in 1989 and Tompkins disposed of his interest in Esprit the following year, making him $125m. The company was subsequently sold to a consortium of investors in 1996.

Since the 1980s Tompkins had immersed himself in ecological writings by authors such as Wendell Berry, whose words he would often quote: “We must change our lives, so that it will be possible to live by the contrary assumption that what is good for the world will be good for us.” By now disillusioned with the clothing industry, a business he regarded as “intellectually vacuous”, he resolved to “stop selling people things they don’t need”, as he later said.

He had first visited Chile as a teenager to take part in ski racing. In 1990 he moved to the country, turning environmental theory into action and creating the Foundation for Deep Ecology, Tompkins Conservation and Conservacion Patagonica.

His first project was the acquisition of a 42,000-acre tract of land in the Reñihue River Valley in Palena province, a virtually abandonned area whose biodiversity he sought to preserve. Through his Conservation Land Trust he added another 700,000 acres, turning it into Pumalin Park, a nature sanctuary. By the time of his death he and his second wife Kris and their foundations managed over 2m acres of land across Chile and Argentina.

“Land use is highly political here, more than most places: if we wanted to retire in peace we wouldn’t be here,” he said in 2009, reflecting on his projects. “These parks are our life’s work, not the clothing chains we created... We are the ones who keep putting obstacles in our own way by buying more land. I’m a troublemaker and I’m proud of it. We know what to expect – more confrontation, more outrage, more mistrust.”

When he was interviewed last year his apocalyptic vision of a future without urgent action on the environment foresaw humanity, as he put it, “on a sand dune with Norwegian rats and cockroaches... We’re not believers in the myth of progress. This requires systemic analysis and gives us an entirely different view of development. It’s common sense that the world has gone awfully wrong. We need a major rethink of what development means.”

Tompkins had been boating with five others on Lago General Carrera in the Patagonia region of Chile. Gusting winds had created waves up to nine feet high, overturning his kayak. Suffering from hypothermia, he was flown to the local Coyhaique Regional Hospital but stopped breathing when he arrived. His companions all survived.

His former wife, Susie Tompkins Buell, said in tribute, “I’m incredibly saddened by this, but he lived on the edge... He used to come home from adventures and say, ‘Well, I cheated death again.’ That’s the way he lived. He was a very inspired person. There wasn’t anything he thought he wanted to do that he didn’t do.” µ MARCUS WILLIAMSON

Douglas Rainsford Tompkins, businessman and conservationist: born Conneaut, Ohio 20 March 1943; married 1963 Susie Buell (divorced 1989; two daughters), 1993 Kris McDivitt; died Patagonia, Chile 8 December 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies