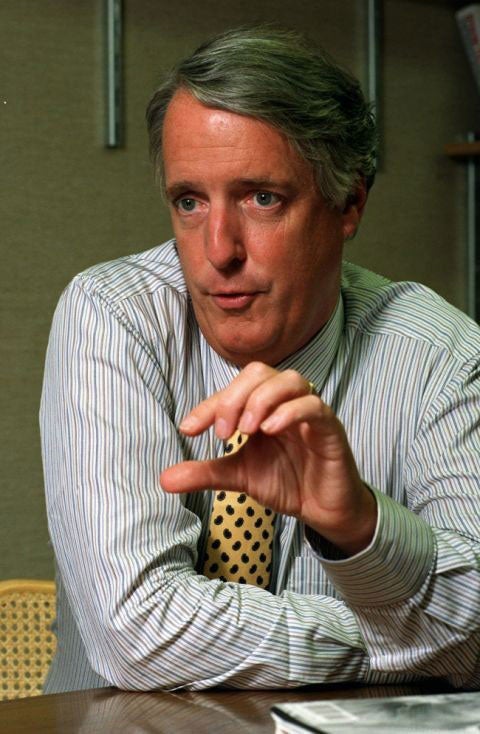

Joe McGinniss: Author who was lauded for ‘The Selling of the President 1968’ but was later attacked for his journalistic ethics

When he was 26, Joe McGinniss wrote The Selling of the President 1968, a landmark study of the uses of advertising in presidential campaigns. It stayed on the US bestseller lists for seven months, making McGinniss the youngest living author, up to that point, to have a No 1 non-fiction bestseller.

At 40 he published Fatal Vision, a page-turning tale about Jeffrey MacDonald, an Army doctor who continued to maintain his innocence long after he was convicted of murdering his wife and two daughters. It sold millions of copies, was made into an NBC miniseries and was hailed as a true-crime classic. But in later years, the book was at the centre of an impassioned debate about journalistic ethics, which came to overshadow McGinniss’s early reputation as one of the leading non-fiction authors of his generation.

McGinniss was still writing until shortly before his death, chronicling his struggle with cancer in Facebook updates and in an unfinished book, but in many ways he became better known for what people said about him than for what he actually put on the page. In 1968, McGinniss overheard an advertising executive say that his company had acquired the “Humphrey account.” Until that moment, McGinniss had not realised that presidential campaigns hired teams of advertisers to sell their candidates like a brand of soap.

When handlers of the Democratic candidate Hubert Humphrey turned down McGinniss’s request to go behind the scenes, he approached the Republican candidate, Richard Nixon. Nixon’s people agreed to let him into the inner sanctum. “This is the beginning of a whole new concept,” said one of Nixon’s leading imagemakers, Roger Ailes, who later became head of Fox News. “This is the way [presidents] will be elected forevermore. The next guys up will have to be performers.”

The Selling of the President 1968 became a runaway bestseller and was made into a Broadway play. The book irreverently pulled back the curtain on political marketing and heralded a promising career for its author, the youngest writer other than Anne Frank to top the non-fiction list up to that point. McGinniss published two books in the 1970s, then journeyed to Alaska for Going to Extremes, his 1980 account of the dark side of the Alaskan dream.

In the late 1970s, McGinniss met MacDonald, a former Army doctor whose pregnant wife and daughter had been bludgeoned and stabbed to death in 1970 at their home in North Carolina. They began on friendly terms, and McGinniss agreed to share up to a third of the profits from a book. The doctor said his family had been attacked in the middle of the night by a Charles Manson-like group of hippies, chanting “Acid is groovy.” But MacDonald was convicted of murder in 1979, and McGinniss came to believe he was a manipulative psychopath.

When Fatal Vision appeared in 1983, Ross Thomas praised it in his Washington Post review as “an absorbing and totally damning indictment of Dr Jeffrey MacDonald.” Most reviewers agreed, but Christopher Lehmann-Haupt of the New York Times had one caveat in an otherwise laudatory review: “There are bound to be those readers who feel that McGinniss has exploited and betrayed a friendship.”

MacDonald sued McGinniss for $15 million, saying he had been betrayed by the author, and the case was settled out of court, with McGinniss’s publishers paying MacDonald $325,000, in return for MacDonald’s agreement that McGinniss had done nothing legally wrong.

But the case took another turn in 1989 when Janet Malcolm wrote a two-part series for The New Yorker, “The Journalist and the Murderer,” later published as a book. Her opening lines have been repeated in American journalism seminars ever since: “Every journalist who is not too stupid or too full of himself to notice what is going on knows that what he does is morally indefensible. He is a kind of confidence man, preying on people’s vanity, ignorance or loneliness, gaining their trust and betraying them without remorse.”

Malcolm dissected McGinniss’s career, saying she found evidence of deceit and a willingness to ingratiate himself with people he later betrayed. Others looked at the case, including film-maker Errol Morris, who criticised McGinniss in a 2012 book. MacDonald continued a series of legal appeals of his conviction, all of which have been rejected in court.

McGinniss wrote a long, point-by-point rebuttal of Malcolm’s article, but never overcame the suspicion that he had betrayed the trust of a source. “Malcolm’s portrait of McGinniss is so damning and her portrait of MacDonald so noncommittal,” David Rieff wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “that one sometimes has to wonder about an approach in which a writer’s dishonesty is treated with more heat than the murder of three human beings.”

McGinniss was born in 1942 in New York, where his father ran a travel agency. He graduated from the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and worked at newspapers in Port Chester, New York and Worcester before going to Philadelphia.

He wrote several more books about true crime and sports, but the furore over Fatal Vision seemed to sap his strength as a writer. His 1993 biography of Senator Edward Kennedy, The Last Brother, was widely derided for imagined dialogue and other deficiencies.

In 2010, while researching a biography on Sarah Palin, McGinniss rented a house next door to the 2008 Republican vice-presidential candidate in Wasilla, Alaska, triggering outrage from her supporters. Todd Palin complained of McGinniss’s “creepy obsession with my wife.” But regardless of the risks, McGinniss believed a writer had to dive into a story, to live in his subject’s world to report it with fidelity and understanding. “For me,” he said, “the only valid kind of writing is simply one guy telling you where he’s been, what he knows and feels.” µ

Joseph McGinniss, author: born New York 9 December 1942; married firstly Christine Cooke (two daughters, one son), secondly Nancy Doherty (two sons); died Worcester, Massachusetts 10 March 2014.

© The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies