Michael Collins: Apollo 11 astronaut who helped the first humans to land on the moon

He piloted the command module while Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin explored the lunar surface

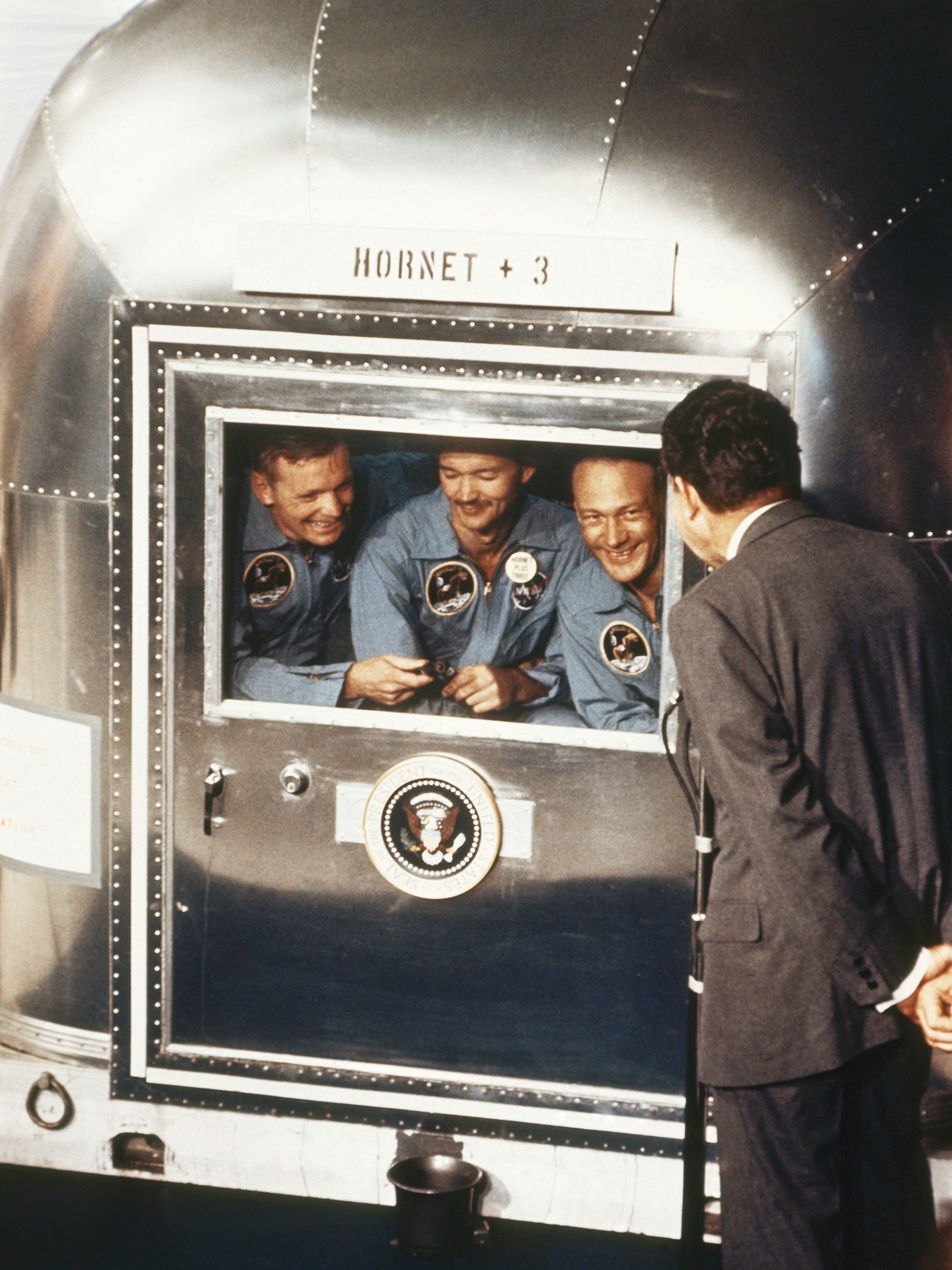

Michael Collins, who has died of cancer aged 90, was the often forgotten third man on the historic 1969 Apollo 11 space mission. While Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first humans to walk on the moon, he was circling it in the Columbia command module.

With 650 million television viewers watching worldwide, Armstrong declared to those observing nervously back at Nasa’s mission control in Texas: “Houston. Tranquillity base here. The Eagle has landed.”

This reference to the landing spot and the lunar module was followed a full six hours later – after a period of rest and preparation – by mission commander Armstrong’s historic moment as he opened the Eagle’s door and placed his feet on the moon, uttering the immortal words: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Aldrin followed in his footsteps 20 minutes later.

While those on Earth had the pair’s names etched firmly in their memories as the astronauts spent more than two hours walking in moon dust – collecting soil and rock samples, setting up scientific experiments and planting the Stars and Stripes – Collins was the one taking a backseat and never achieved the same degree of celebrity.

Nevertheless, his role in the mission was crucial. Before his fellow astronauts’ departure for the final leg, he pressed the button to undock the lunar and command modules, with Armstrong reporting: “The Eagle has wings.”

He then tracked the lunar module optically to ensure it was undamaged, with its landing gear correctly deployed, before its slow descent towards the crater-pocked lunar surface.

Once it had landed, on 20 July, Collins spent more than 22 hours piloting Columbia 60 miles above in orbits of the moon, readying the capsule for Armstrong and Aldrin’s return while worrying about their safety.

During each orbit, he was out of radio contact with mission control for 48 minutes as he passed round the far side of the moon. He wrote: “I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it.”

But Collins said he never felt lonely, instead declaring feelings of “awareness, anticipation, satisfaction, confidence, almost exultation”.

He acknowledged in his 1974 autobiography, Carrying the Fire: An Astronaut’s Journeys, that he did not have “the best of the three Apollo 11 seats” but added: “This venture has been structured for three men, and I consider my third to be as necessary as either of the other two.”

When the two moonwalkers returned in the Eagle on 21 July, he carefully manoeuvred his craft to align with theirs for re-docking, then secured the two.

He left a memento of his time aboard the command module when, during the second night following their return, he wrote in its lower equipment bay: “Spacecraft 107 – alias Apollo 11 – alias Columbia. The best ship to come down the line. God Bless Her. Michael Collins, CMP.”

The mission finished with splashdown in the Pacific, off Hawaii, on 24 July after a journey lasting just over eight days.

The following month, six million people cheered the three American heroes in parades on the streets of New York and Chicago, before they attended an official state dinner in Los Angeles to celebrate their realisation of president John F Kennedy’s 1961 goal to land a man on the moon and return him safely to Earth that decade.

The wider implications of beating the Russians to this were acknowledged with a global tour that took the trio to more than 20 countries and brought them into the presence of many world leaders.

Collins’s pre-Nasa career was as a fighter pilot, following his father, brother, uncles and cousin into the armed services.

He was born in 1930 in Rome, where his father, James, a major-general in the US army, was the American military attaché. He was of Irish heritage, while Michael’s mother, Virginia (née Stewart), was from a family with British roots.

As James took various postings across the United States, Michael attended St Albans School, Washington.

After dismissing ideas of a career in medicine, he enrolled at the US Military Academy, graduating in 1952 with a science degree, then joining the US air force.

He followed two years’ training by being posted to an American base in Chaumont-Semoutiers, France, where he survived his F-86 jet fighter catching fire during a Nato exercise by bailing out.

Then, in 1960, he joined the test pilot school at Edwards Air Force Base, California. When John Glenn became the first American to orbit the Earth two years later – three times, in the space capsule Friendship 7 – he was inspired to apply to join Nasa, but was turned down twice.

It was third time lucky for Collins when he applied again in 1963. He trained as a backup pilot on Gemini 7, a 1965 mission to investigate the effect of 14 days in space on the human body, but was not needed.

His first big moment came the following year when he joined John Young on the Gemini 10 mission to conduct rendezvous and docking tests with a target vehicle. Not only did he complete a brief spacewalk, but he became the first person to visit another craft in orbit.

Collins got over his disappointment at being removed from the Apollo 8 space mission – the first crewed orbit of the moon, in 1968 – as a result of undergoing surgery when he was announced as the command module pilot on Apollo 11.

He retired from Nasa and the US air force in 1970, when president Richard Nixon persuaded him to serve his administration as assistant secretary of state for public affairs in the State Department, a PR role.

Unhappy in it after a year, Collins joined the Smithsonian Institution to plan the development of its National Air Museum into the National Air and Space Museum, serving as its director (1972-78), then under-secretary.

Following a period as vice president of a Virginia aerospace firm, he formed Michael Collins Associates in 1985 to work as a consultant.

His achievements earned him the Nasa Distinguished Service Medal, Distinguished Flying Cross, Congressional Gold Medal and Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Collins was also the author of Liftoff: The Story of America’s Adventure in Space (1988) and a children’s book, Flying to the Moon and Other Strange Places (1976).

Armstrong died in 2012, while Aldrin is still alive, aged 91.

In 1957, Collins married Patricia Finnegan, who died in 2014. He is survived by their daughters, Kate and Ann. Their son, Michael, died in 1993.

Michael Collins, astronaut, born 31 October 1930, died 28 April 2021

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks