Mike Westmacott: Mountaineer who helped in the first ascent of Everest

When several hundred breathless people reached the summit of Everest last month they did so thanks in no small measure to the labour of an unsung group of Sherpas known as the "Icefall Doctors" who maintain a passageway through the jumble of teetering ice cliffs and gaping crevasses of the Khumbu Icefall. Mike Westmacott was in essence the prototype Icefall Doctor. While Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were making the first ascent of the 8850m mountain in 1953 it was Westmacott and his team of Sherpas who kept open the expedition's vital line of supply and return.

The Khumbu Icefall is the most objectively dangerous place on the standard route on the Nepal side of Everest, a cascade of ice rising 600m from base camp to the Western Cwm, the glacier trench that gives access to the upper part of the mountain. It has claimed many lives, another in April this year when a Sherpa fell into a crevasse from one of the aluminium ladders used to span the voids.

In 1953 the Icefall was still relatively unknown and much feared. A 1951 reconnaissance expedition, including Edmund Hillary, had penetrated to the lip of the Western Cwm, and in spring 1952 a Swiss team rigged a rope bridge across the giant crevasse that bars the top of the Icefall and entered the Cwm for the first time. Though the Swiss got tantalisingly close to the summit, Tenzing Norgay and Raymond Lambert reaching almost 8,600m, fatigue and bad weather finally forced them back.

As the Swiss were trying and failing on Everest young Michael Westmacott was embarking on his career as a statistician and enjoying a successful climbing season in the Alps. Everest hadn't seriously entered his head. That summer he had spent three weeks in Switzerland and succeeded on a clutch of classic routes that would still be the envy of alpinists today, then finished with a traverse of the Matterhorn.

"As we made for our doss at Satfelalp, Dick [Viney] said, 'We've had a marvellous day's climbing, Mike. Nothing like in the Himalayas – all slog, slog, slog – but wouldn't you give anything to go to Everest next year?' He was right, but I don't think it had occurred to me before to do anything about it."

The quote comes from a short recollection Westmacott wrote for the Alpine Journal on the 40th anniversary of the Everest ascent. Westmacott was the most self-effacing of men and first-person accounts of his climbing emerged only in low-key snippets.

Michael Westmacott was born in 1925 in Babbacombe, Torquay, and educated at Radley College, Oxfordshire, his first climbing adventures scrambles on the limestone and sandstone cliffs behind the Torquay beaches. Westmacott served as a junior officer in King George V's Bengal Sappers and Miners, building bridges in Burma with 150 Japanese PoWs under his command. Then came Oxford, where he studied mathematics, adding a further year of statistics, and joined the university mountaineering club – initially more for the comradeship. His first rock climb was the Napes Needle in Wasdale, in floppy tennis shoes on a cold day in December 1947.

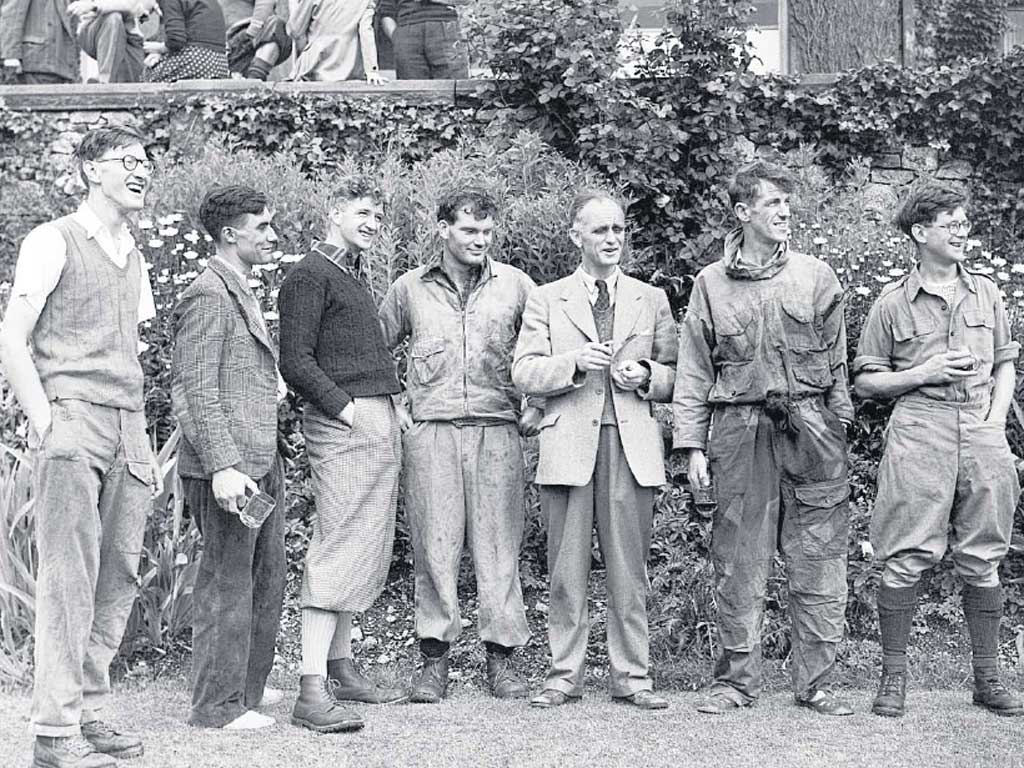

The OUMC was on the cusp of a post-war renaissance and together with its Cambridge counterpart would provide many of the leading climbers of the 1950s. The clubs were a natural place for Col John Hunt to cast an eye when assembling his cast for Everest. From Cambridge he chose George Band, at 23 the youngest member of the team, and from the Oxford side Westmacott, 27 and employed on statistical investigation at the Rothamsted Experimental Station. They would become life-long friends. (George Band, Independent obituary, 2 September 2011.)

Hunt had been particularly impressed by the young man's 1952 season, but as an ex-Sapper, Westmacott had other skills and was given responsibility for structural equipment, notably the ladders needed for bridging crevasses. Westmacott's first big job above base camp was to join Hillary and others in finding a route up the maze of the Icefall. Landmark names like "Mike's Horror" and "Atom Bomb Area" reflect the hazardous nature of the beast – Westmacott performing "a fine feat of icemanship", according to Hunt, to negotiate one particularly awkward crevasse. Higher up he helped push the route and carry loads on the Lhotse Face, but he was dogged by sickness and reluctantly had to retreat, exhausted, having reached around 7,000m. He spent the succeeding days in the Icefall, engaged on the risky task of keeping a route open as the ice shifted. He was back up at the camp at the head of the Western Cwm when Hillary and Tenzing returned triumphant after having, as the former put it, "knocked the bastard off".

Westmacott accompanied James Morris (later Jan) of The Times down in order to get the news back to London in time for the Coronation. It was late in the day and, as Westmacott recalled, "not the most sensible thing I've done ... By the time we got to the bottom we were very tired indeed and it was getting dark." Morris had noted how much the Icefall had changed. "The whole messy crumbling cataract was messier and crumblier than ever before," she wrote in Coronation Everest. Westmacott had been working in this "horrible place" for 10 days. "I have often thought of Westmacott since, immured there in the icefall, and marvelled at his tenacity."

Though few of the expedition members realised it at the time, the Everest experience shaped their lives. A dinner invitation led to Westmacott's courtship of Sally Seddon, then at the Royal College of Music, and a long and happy marriage; they climbed in the Alps, North America and the UK,. Westmacott left Rothamsted to work for Shell as an economist.

Most of Westmacott's years with Shell were spent working in London and living in Stanmore. He retired in 1985 and in 2000 the couple moved to the Lake District, close to friends and the best rock climbing in England.

Westmacott was by now one of the mountaineering aristocracy, though perhaps its least flamboyant, and active in the affairs of the Alpine Club and the Climbers' Club. He served as president of both and leaves a lasting legacy through his development of the AC's Himalayan Index, a computer database that now lists more than 4,000 peaks of above 6,000 metres and their climbing histories.

Michael Horatio Westmacott, mountaineer, statistician and economist: born Babbacombe, Torquay 12 April 1925; married 1957 Sally Seddon; died Grange-over-Sands, Cumbria 20 June 2012.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies