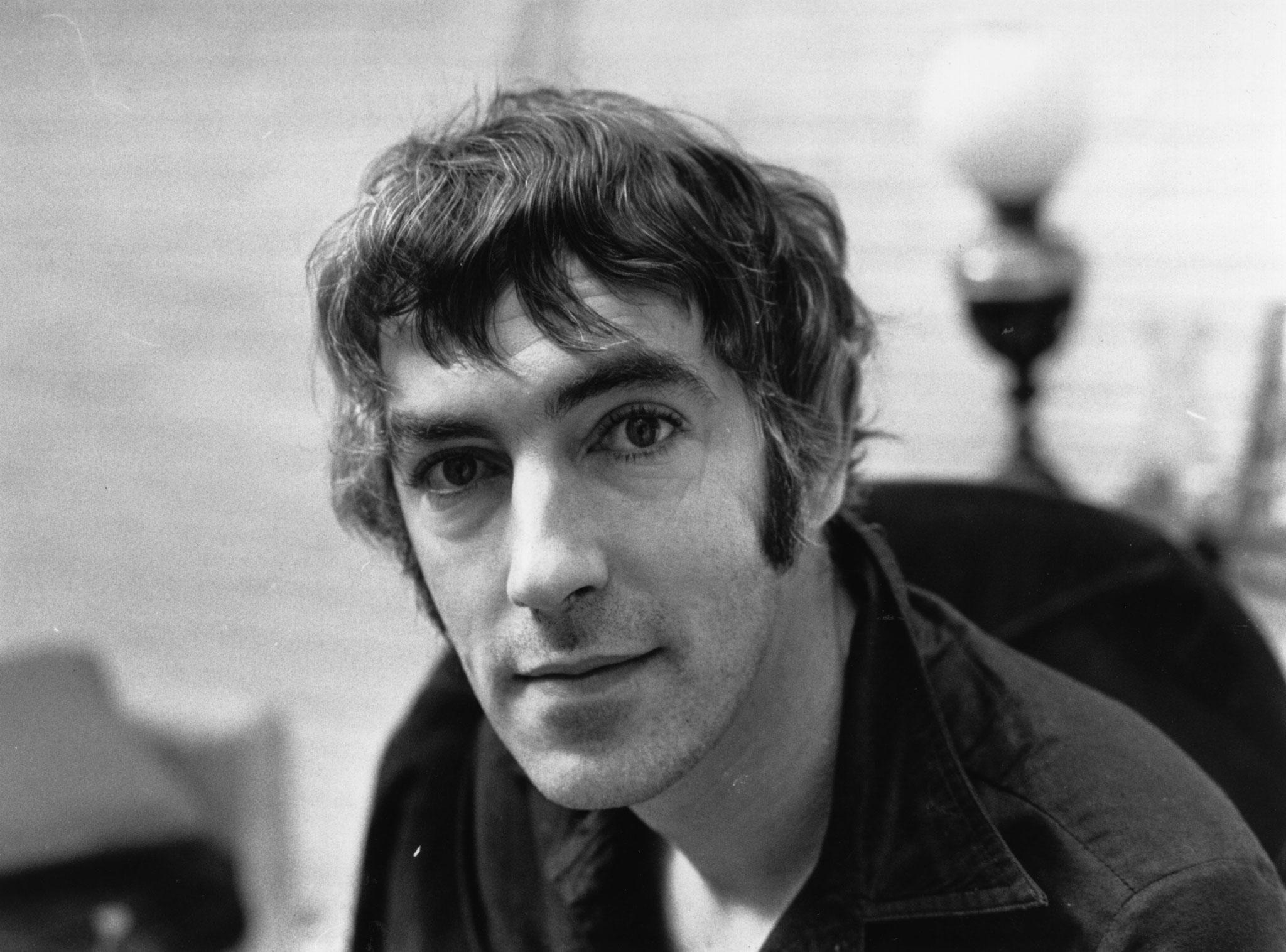

A Life in Focus: Peter Cook, giant of British comedy who inspired several generations

The Independent revisits the life of a notable figure. This week: Peter Cook, from Tuesday 10 January 1995

Many years ago, when “alternative comedy” was all the rage, Peter Cook made one of his – then increasingly rare – television appearances, in a show done before a studio audience who thought comedy had been invented by Monty Python in some prehistoric past and brought to the peak of perfection by Rik Mayall.

Beyond the Fringe was probably not even a name to them. Ben Elton, who was compering the show, introduced Peter as “The Boss”. Which was fair enough. The liberating possibilities for comedy which the new generation had seized on, not just the surreal but the scatological and the obscene, had been discovered – or more properly rediscovered – in the first place for them by Peter Cook, whether they acknowledged it or not; of all the people I have known or seen toiling in that particular vineyard he is the one indisputable genius.

The direction his work took had nothing whatever to do with marketing a talent, finding a niche, developing a career. It had everything to do with a compulsive articulation of his view of life – beady, remorseless, hilarious.

Cook’s name is associated with the “satire boom” of the Sixties. And indeed he came to fame as one of the four writer/ performers – the others were Alan Bennett, Jonathan Miller and Dudley Moore – of Beyond the Fringe, advertised as a “satirical revue”. At the same time he created the Establishment, billed as “London’s first satirical nightclub”; these two entertainments were highly successful both here and in New York, at a time when some of the structures of traditional British institutions were falling apart.

“Satire” is sometimes given at least part of the credit for the collapse of the old order (in the form of Harold Macmillan’s administration); another view is that it was just a lot of undergraduates repaying the state for their expensive educations by being rude to the government. Cook’s own view of the satire boom was as disenchanted as his view of its targets: he said of the Establishment Club that it was to be modelled on the political cabarets of Berlin in the Thirties “which did so much to prevent the rise of Adolf Hitler”.

Peter Cook's life and career

Show all 10Still, a satirist is what he was, but only if you use the term for its richest and most complex connotations. Northrop Frye wrote of satire that “it demands (at least a token) fantasy, a content recognised as grotesque, moral judgements (at least implicit), and a militant attitude to experience”. Its distinguishing mark is the “double focus of morality and fantasy”.

Cook wouldn’t easily have forgiven me for calling up this academic artillery barrage, but those phrases perfectly describe the way his humour worked.

He would be seized by an idea (in his case the image is almost literally true) and pursue it through vertiginous spirals of logic, allusion, and spectacular connections until it, and his audience, was exhausted. The premiss would often be simple, and so self-evident no one had thought to remark on it: the vengeful judge, or the miner who wanted to be a judge but failed because he didn’t have the Latin, despite his preference, on balance, for the trappings of luxury over the trappings of poverty. His Harold Macmillan, defending Britain’s nuclear policy and the alleged inadequacy of the “four-minute warning” preceding nuclear attack: “I would remind them there are some people in this great country of ours who can run a mile in four minutes.” A joke which brilliantly clamped its teeth on that era’s self-delusion and hopeless nostalgia for power and glory.

Just to quote examples does Cook a disservice, because it never stopped, anyway as long as I knew him, the fountain of original, freshly minted stuff, unmediated by political correctness, or any other form of correctness.

His performing partnership with Dudley Moore was unique. Although it contained a certain amount of creative tension, it was a spontaneous combustion of comic invention, which took no prisoners, in film (such as Bedazzled, 1968, The Bed Sitting Room, 1969, The Hound of the Baskervilles, 1977), on television (Not Only But Also, 1965-73) or on stage (Behind the Fridge, 1971-72). The obscenity in their Derek and Clive records was very liberating. The desire was not to shock for its own sake but, Cook said, to get the speech rhythms right and knock out barriers to invention. Cook had a remarkable feeling for language. He had an unblinking bullshit detector which never failed him; and he would never draw back in his comments.

Some kinds of talent are as much an affliction as a gift. Inside Cook’s head lived demons of insight and inventiveness, always insistent, but that isn’t to suggest he was some kind of comic Savonarola, a bitter anchorite brooding on iniquity. On the contrary, Cook was rather a dashing figure, with a penchant for the more glittery side of showbusiness. Indeed, he sometimes gave the impression that his own ambition was to be a rock star and/or a suave leading man in Hollywood movies, a sort of latter-day Cary Grant, neither of which roles he was cut out for.

What he should have been, and for a while was, was an impresario-producer, because he was a genial and inspiring collaborator who had a flair for getting things on. He was a shrewd businessman and the moving spirit behind and main investor in Private Eye for three decades. It has been suggested that Cook “did not fulfil his promise”. What does that mean? What is necessary for fulfilment? That you should have your own peak-time TV show? Get to run the Royal Opera House, or the National Lottery? Be knighted? Peter Cook was an intelligent, honest, supremely funny man. And, I hope, a happy one.

Peter Cook, comedian, born 17 November 1937, died 9 January 1995

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies