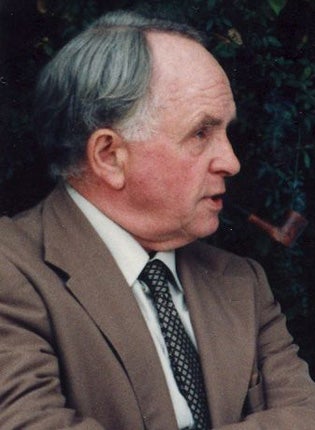

Professor Pat Thompson: Historian whose influence came through teaching rather than his writing

For four decades tutor at Wadham College, alternately acerbic and avuncular, iconoclastic and inspiring, and always generous with his time, A.F. '("Pat"') Thompson was a major force in modern British history teaching and research at Oxford. His influence did not stem from publications, although his evaluation of trade unions' political role in A History of British Trade Unions since 1889, volume 1 (1964; co-authored with Hugh Clegg and Alan Fox), and a 1948 article on "'Gladstone's Whips at the General Election of 1868"', initiated significant reconsiderations.

Otherwise, too few miniatures survive as samples of an elegant and sinuous mind. He regretted this paucity – the failure to write not 10 books, rather 20 articles that "'really made people sit up and think about a particular topic"'. It was a characteristic discrimination. He pursued the objective instead through tutoring undergraduates and supervising graduates, for whom he introduced research seminars. He was on the steering committees of the Oxford Historical Monographs and the Gladstone Diaries. Achievement thus came vicariously. His pupils, who are legion, include Melvyn Bragg and Julian Mitchell. Colin Matthew and Ross McKibbin lead those who built substantial academic reputations. A festschrift, which I edited, Politics and Social Change in Modern Britain, appeared in 1987.

The Thompson style of teaching, at its best delivered from a Windsor armchair and wreathed in Player's Navy Cut, was angled at the individual. He affirmed "the old methods, but endlessly adapted". This meant "seeing people in their own terms", before shaking them up. Further, "if at the same time you can tell them something they may not have noticed, then you ought to do so". Here was a reductionist formula for a sophisticated exercise, designed to unfold an understanding of why people acted as they did. It was penetrating and witty, his sympathy laced with scepticism; indeed, always seasoned with salt, pepper and not a little vinegar.

He also proved an accomplished performer before bigger audiences, lecturing without notes like A.J.P. Taylor. He knew this was showmanship more than scholarship: he laughingly recalled Taylor taking a handful of postcards from his pocket and reading off them, as if verifying sources, when almost all were blank. Thompson did not so dissemble.

The philosophy of history interested him but he resisted ideologically driven writing and novelty methodologies. Idealism he did not discourage, but proportionate, tempered by realism. In adolescence he looked to Cripps and a Popular Front, then moved centre-left behind Gaitskell who "captured my imagination in a way that none of the others had ever done". His pleasure in Michael Foot, a Wadham alumnus, was purely personal. Later, disenchantment was manifest. To undergraduates panting for a Labour win in 1964, after 13 years of Conservatism, he drily remarked that since his father had voted for Ramsay MacDonald, he didn't see why they shouldn't vote for Harold Wilson.

Arthur Frederick Thompson was born in 1920 in Preston, eldest child of a Londonderry-born Inland Revenue official who became senior finance officer at Stormont. While boarding at Campbell College, Thompson. was confirmed into the Church of Ireland. The move to south London, upon his father's transfer to Somerset House in 1936, was intellectually liberating as he became a day boy at Dulwich College. Here originated the nickname "'Pat'" – a tribute to the limited imagination of English schoolboys, for whom a brogue signalled a Paddy. Initially a classicist, Thompson embraced history after encountering the same master who taught K.B. MacFarlane, the pre-eminent medievalist at Magdalen College, Oxford, where Thompson became an exhibitioner in 1939.

During the admissions interview, he took against "'a funny little man who sat with his back to me, reading The Times ... he kept rattling the newspaper as MacFarlane very politely led me about the Holy Roman Empire"'. This was A.J.P. Taylor, into whose orbit Thompson eventually gravitated, drawn by "his wonderful articulate originality" and brisk manner; yet MacFarlane's subversion of panoptic historical theories and insistence on the human agency that shaped institutions remained with him, together with an inhibiting perfectionism.

Following his First in 1941, he joined the Worcestershire Yeomanry, a territorial Artillery unit, undertaking parachute and glider training before being dropped into Normandy on D-Day, his 24th birthday. Three weeks later, with shrapnel wounds in both legs, he was out and spent the rest of the war with GCHQ at Bletchley. On demobilisation, he returned to Oxford to pursue research aiming to marry Namierite analysis with the new political science of psephology and apply it to the late 19th century. He was elected a senior demy at Magdalen; then, in a heady coincidence, offered a tutorial fellowship at both Queen's and Wadham.

Academic life was not the only option. In 1946 he passed near the top of the civil service exam, just behind Edward Heath; he chose Wadham, bewitched by its Warden, Maurice Bowra. There he remained, apart from visiting professorships at Stanford (three times) and McMaster. He served as Domestic Bursar, Senior Tutor, Tutor for Graduates and Sub-Warden. He observed Wadham's transformations with irreverent affection, approved its admission of women, and in retirement fund-raised for another history post.

Pat Thompson revelled in the dons' social life, his quick wits excelling in banter. At home he had the perfect foil, his wife Mary, who read botany at Somerville. They married in 1942, at a registry office with Alan and Margaret Taylor as witnesses, afterwards submitting to a church service to appease parents. The marriage, immensely strong, was tested by misfortune: Johnny, their second son, born in 1947, was brain-damaged and required professional care, and Alan, born in 1943, died of cancer in 1989.

Philip Waller

Wadham was never a smart college, writes Julian Mitchell, but in the 1950s, under the booming wardenship of Maurice Bowra, it was academically one of the most successful in Oxford, thanks largely to an influx of new and often battle-hardened dons who arrived after the war. Among these were Lawrence Stone and Pat Thompson, who shared the history teaching.

Stone was tall, rangy, energetic, frequently alarming, inspiring but, to his enemies, rash. Thompson, with barely disguised amusement, played the part of his solidly built, pipe-smoking, worldly but reliable straight man. Under the apparently comfortable appearance, though, there was a frequently insecure man, who could be extremely sharp – with himself, probably, even more than with others.

C.P. Snow's The Masters (1951), about Cambridge college politics, was sneered at in Oxford, but Pat, with his family sorrows and his cynical approach to life could have come straight from its pages. Knowing so much, from his work on the rise of political-party organisation in the late 19th century, about the deviousness of national politicians, he relished the often even more devious politics of the university, where his smiling approach could suddenly include a brief but devastating destruction of character – though the smile remained.

But when it came to teaching us modern British history (which meant in those days stopping at the House of Lords crisis of 1909-11), he was quite straightforward. The object was not merely to make us learn something about the not-so-distant past, but, with his famous last tutorials before Finals, master classes in exam technique, to get us rather better degrees than we deserved. Equally Snovian was the delight he took in "placing" his pupils through his connections in the outer world, another form of political activity in which he shone.

Arthur Frederick Thompson, historian: born Preston 6 June 1920; Fellow in Modern History, Wadham College, Oxford, 1947-87 (subsequently Emeritus); married 1942 Mary Barritt (died 2003; one daughter, one son and one son deceased); died Oxford 9 October 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks