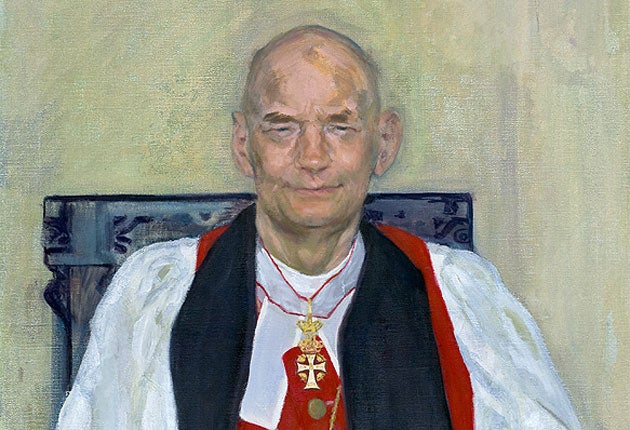

The Right Revd Dr Kenneth Stevenson: Colourful priest with a special interest in liturgy who became a popular Bishop of Portsmouth

He was drinking champagne and listening to his favourite Bach only hours before his death in hospital.

With the passing of Kenneth Stevenson the episcopate has lost one of its most scholarly, unusual and colourful characters.

Born and brought up in Edinburgh, he was the heir to a distinguished clerical dynasty. He was of Danish ancestry – his maternal grandfather had been the Bishop of Aarhus with forebears as Lutheran pastors going back to the Reformation. Kenneth's father (following a distinguished architecture practice_ and father-in-law were both Anglican priests and two of his brothers-in-law, David Tustin and Peter Forster, are bishops.

Ordained in 1973, Kenneth brought a speed of mind and depth of learning noticeable for its historical sweep and perspective. His prodigious output of articles and books, particularly on liturgy, combined painstaking theological study with spiritual devotion. Whether as a member of the Diocesan Board of Ministry or later, nationally, with the Liturgical or Doctrine Commissions or National Society, he understood his calling as an apostolate to make the Gospel intelligible to those outside the church.

Never narrowly churchy, he defied all attempts to label him. With the evangelicals he always challenged them to know their Bibles better; with the Catholics to be more aware of the richness of tradition. Any prissiness among the Catholics would be met with the remark that this made him want to reach for his Lutheran ruff!

Kenneth was ecumenical and international in his thinking. He enjoyed his time as a Visiting Professor at the Catholic University of Notre Dame at South Bend, Indiana, and made a significant contribution to the Anglican-Lutheran dialogue. For him the wheels of ecumenism were oiled by personal friendship, and his network of contacts bore witness to this. He was always fun, and an important part of his success as a University Chaplain in Manchester and teacher in the Faculty of Theology was his ability to encourage his students.

He loved the Church of England and her vocation to speak to the nation. An expert on the Caroline Divines, he had a great affection for Lancelot Andrewes, the 17th-century Bishop of Winchester, and the ability of that prelate to speak with courage and wisdom to those in authority. As somebody who abhorred ghetto religion, Kenneth relished his opportunities as Rector of Holy Trinity, Guildford to preach at civic services and make links with the town hall and business communities. The parish was delighted when he was named Bishop of Portsmouth in 1995.

A young Diocese, for the previous 20 years Portsmouth had been led successively by two unmarried Bishops, Ronald Gordon and Timothy Bavin. The Diocese wanted a family man as their next Bishop and Kenneth ran the Diocese as a family. He was wonderfully supported by his wife Sarah, whose hospitality was a byword and who was described by Robert Runcie as the best cook in the Anglican Communion. He gathered a loyal staff around him and was genuine in his delegation. He was perceptive, could be especially caring in a crisis and was good with those who were struggling. A sensitive man, he was rocked by problems at the Cathedral in the early part of his episcopacy and felt hurt and betrayed.

Always looking outwards, Kenneth enjoyed his time in the House of Lords and was for a time the convenor of the Lords Spiritual, his intelligent and thoughtful contributions being much valued. Part of his attraction was that he was in many ways an unconventional Bishop with his donnish demeanour, tweed jackets and bow ties. He made great links with the naval establishment in Portsmouth, they enjoying his directness and playful indiscretion.

Kenneth always categorised Bishops as prefects or rogues; he classed himself as a rogue. In the House of Bishops he was friendly and welcoming to junior colleagues, characteristically subversive and keen to recall the House to its theological work. He became impatient in his last years with a church seemingly obsessed with its domestic agenda when he was dealing personally with issues of life and death. He was diagnosed with leukaemia in 2005; his last years in office were difficult for him and for the Diocese and he showed great bravery. People loved and admired him, his vulnerability enabling others.

Kenneth knew that his strengths were also his weaknesses. A big man with a big mind, he was visionary in getting the Diocese to get to grips with its future sustainability concerning ministry and buildings. However, he knew that sometimes he found it difficult to focus on the small scale and deal with the nitty-gritty. He was a larger-than-life character and, never one to paint with a sombre palette, he could be unaware of his position. A complex person, there was something about him that was always the outsider. However, he knew he was loved and accepted by God and that in his life-giving and sustaining family were the seeds of the domestic church. He is survived by his wife Sarah and their children James, Kitty, Elisabeth and Alexandra. It rejoiced Kenneth's heart when James joined the generations-old family firm in 2007.

Peter Townley

I first met Kenneth Stevenson in 1978, at the inaugural meeting of the Society for Liturgical Study, writes Bryan D Spinks. Donald Gray and Geoffrey Cuming had invited a number of "younger" scholars (and we were young then!) who were studying liturgical subjects at postgraduate level to Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, Leicestershire, to read papers, with the intention of founding a society to encourage study, and for mutual support in what in the United Kingdom continues to be a Cinderella subject.

I heard Kenneth before I was introduced – his loud laughter from one of the dining tables. His laughter and humour, mixed with scholarship and learning, were among his many gifts. He was Lecturer at Boston Parish Church, Lincolnshire – one of those curious titles left over from the Reformation era, which meant assistant curate but sounded grander. He had completed a PhD at Southampton University on the liturgy of the Catholic Apostolic Church, and Cuming encouraged him to undertake a study on marriage rites. The result, Nuptial Blessing, is still the only serious monograph on this liturgical topic. Kenneth had a flair for writing in a readable manner, as though his topic was a conversation over the garden fence, but with scholarly rigour.

His wit and quick observations on clerical pomposity and petty ecclesiastical politics were legendary. He and I were appointed to the Church of England Liturgical Commission in 1986, and for 10 years were involved in the preparatory work for Common Worship 2000. Kenneth's knowledge would check the more unreasonable and untenable positions of the Catholic wing, though he believed both Anglo-Catholics and conservative Evangelicals had an important part to play in the life of the Church, including its liturgical life. His impish personality often relieved difficult debates. He also helped "name" members of the Commission with inspiration from AA Milne. Bishop Colin James, as Chair, was Christopher Robin, and Kenneth was Pooh; Michael Perham was Piglet, David Stancliffe was Tigger, and on account of my serious face I was Eeyore: Kenneth would often refer to my Barthian or Calvinist frown.

As Bishop of Portsmouth he skilfully gave clear guidance and teaching to his clergy as well as maintaining a healthy output of theological writings on the Anglican sacramental and devotional tradition. His appointment to the House of Lords was a joy for him, and it provided a much-needed escape from the often depressing and tedious side of Church life. But he loved the diocese and they loved him. He chaired a meeting of the Anglo-Nordic-Baltic Theological Conference at Portsmouth during Cowes Week to which I was invited, and I shall ever remember him drinking Pimm's while chatting with the Duke of Edinburgh.

Not long after he had read a paper at the first Yale Liturgy Conference in 2005, we learnt that he had been diagnosed with leukemia. Six months later my wife Linda was diagnosed with the same disease, though a different and more aggressive type, and she lost her battle with the disease in January 2007. Kenneth became for me a symbol of hope and determination.

He retired from Portsmouth in order to give his full energy to recovering from the fatigue that the illness and its treatments had brought, and to spend time with his wife Sarah, who became his constant care-giver. He remained cheerful, thankful, transfigured in body, mind and soul. He continued writing, on academic subjects and also sharing the spiritual journey on which this disease had taken him.

Liturgical scholarship and the Church of England are a little duller with his passing, but he leaves an important legacy – the day I learned that he had died, I read a new essay in which one of his works is cited. I can imagine him saying, "For God's sake stop looking at me with that Barthian frown and have another gin and tonic."

Kenneth William Stevenson, priest: born Edinburgh 9 November 1949; Lecturer, Boston 1976–80; part-time Lecturer, Lincoln Theological College 1975–80; Chaplain and Lecturer, Manchester University 1980–86; Team Vicar, 1980–82, Team Rector, 1982–86 Whitworth, Manchester; Rector, Holy Trinity and St Mary's, Guildford 1986–95; Bishop of Ports-mouth 1995–2009; an Honorary Assistant Bishop, Diocese of Chichester2009-; married 1970 Sarah Glover (one son, three daughters); died 12 January 2011.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies