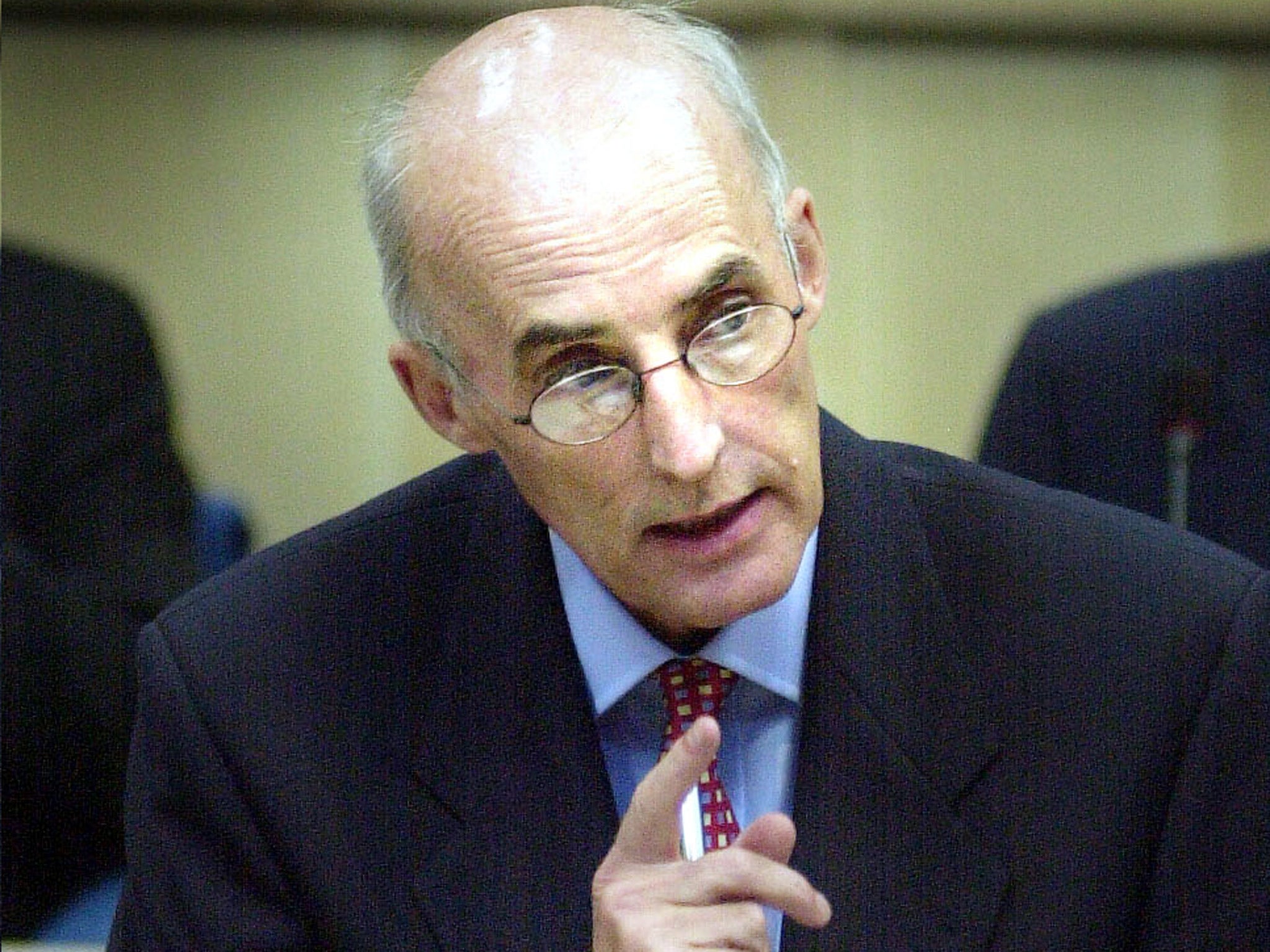

Sam Galbraith: Neurosurgeon who survived a lung transplant and served as Scottish education minister

Galbraith: ‘Anyone who thinks Scotland is a great left-wing nation is wrong,’ he said. ‘We live on the myth that it is perfect’

Whereas a significant number of physicians have been elected to the House of Commons, only two surgeons have become MPs: John Cronin, who represented Loughborough most effectively and who would breeze into the House after lunch, having spent the morning in the orthopaedic operating theatre; and Sam Galbraith, distinguished neurosurgeon.

Galbraith was a most unusual politician. Blunt with his parliamentary colleagues, quick to tell us in no uncertain terms if he thought we were talking nonsense, unashamedly irascible, he had all the decisiveness associated with his demanding profession. He did not suffer fools gladly. Although on account of a difference of opinion I would be consigned to the “fool” category, along with most of my Labour colleagues, I liked Galbraith.

He was born into a socialist family. His father, a schoolteacher of technical subjects, was a key supporter of the charismatic Hector McNeil, who became MP for Greenock in 1941 and Attlee’s Secretary of State for Scotland, and his successor, the equally charismatic Dr J Dickson Mabon. When the latter deserted Labour for the SDP Galbraith was incandescent.

Attending Greenock High School, Galbraith intended to be a missionary, rather at the behest of his Pentecostalist mother. “But,” he told me, “the deprivation all around us in Greenock and Port Glasgow made it clear to me that there were plenty of things that needed doing in this country as well as the Third World.”

He was accepted by the Medical Faculty at Glasgow University. A hard-working student – they had to be in medicine – Galbraith decided that all politics “was a fake”. But he retained his left-wing beliefs, and rather than take part in organised political activity, “I preferred to go meetings and heckle.” Twenty years later there was no one as sharp in interrupting a Member on the green benches and puncturing his or her argument. Honourable Lady MPs, not only Tory, were often his victims.

Galbraith graduated in 1972 and became a resident junior doctor, working round the clock. His interest in neurology was ignited when his Faculty nominated him for a student exchange with the University of Chicago. I asked him, “Sam, why and when did you want to become a surgeon?” I shall never forget his reply, characteristic twinkle in his eye: “Surgeons are always decisive people, the sort of guys who walk right down the centre of a corridor, while physicians walk along the side.”

In 1974 he went to the Southern General Hospital as a registrar, and three years later, at 32, was promoted to consultant. He told me, to my surprise, that neurosurgery was “overrated”. The brain, he pointed out, is held in almost religious awe compared to the other organs, like the stomach; he thought that the brain was by no means the technically most difficult. His only problem was that the penalties of error were very great. Two friends of mine, Professor Bryan Jennett – one of the pioneers in the immunology of organ transplantation – and Guido Pontecorvo, Professor of Genetics at the University of Glasgow, told me Galbraith was an outstandingly innovative young surgeon.

In the mid-1980s it became clear that the hitherto impregnable blue chip seat of Strathkelvin and Bearsden might be winnable – but only with a “horses-for-courses” candidate who could appeal to one of Britain most wealthy and sophisticated electorates. Now, potential Labour candidates are eager; but Galbraith took some persuading – particularly by Brian Wilson, later an influential Minister for Energy – to allow his name to go forward.

Against the political tide Galbraith pipped the sitting MP, the Conservative Party chairman Michael Hirst, by 19,369 votes to 17,187, with Tom Chalmers, national treasurer of the SDP, in third, and a well-respected local teacher, Barbara Waterfield, in fourth.

Shortly after his maiden speech, catastrophe. He was diagnosed with fibrosis of the lung, the only cure for which was a transplant. The first European lung transplant was carried out in Newcastle in 1987, and it was to that University hospital’s division he went: “I was three or four days off dying when I had the transplant and I was resigned to the idea of death. That was not a problem for me – you have to accept your lot in life and I had had two years to accept it.”

Colleagues who visited him spoke highly of the devotion of his wife, who stayed in hospital accommodation with their four-month-old daughter for three months, and his own guts. When he returned to the Commons he told me with a chuckle that he might not be going back to the Himalayas, where he had been in 1985 and where he had first become aware of breathing problems at high altitudes.

As a Scottish Office minister, under Secretary of State Donald Dewar, he had the respect of the Commons and his civil servants. Then in 1999 he was one of two MPs to decide that their future lay with the Scottish Parliament. As Education Minister he antagonised the teachers: responsible in 1999 for the Scottish Qualifications Authority, then in its infancy, and creating bitter controversy, he largely took the rap for officials’ perceived shortcomings.

The real trouble was that he tried to change Scotland’s education system. “Whoever thinks Scotland is a great left-wing nation,” he told me, “is wrong. We find it very difficult to make progress and move forwards. We are too happy with the status quo because we live on the myth that it is perfect – it is not. Sometimes you have to tackle vested interests. If you threaten them they don’t like it, and they stand up against you. Scotland has to shake itself from its myth.”

He was against Blairite reforms to replace failing local authority management with private companies – or, as he called them, “hit squads”. Councils, he believed, should get back to democratically overseeing the system of maintaining standards.

After a year he was moved to Environment, where he frankly had a politically unhappy time. Events took their toll on his health and he retired from public life. In my view Sam Galbraith, that unusual politician, enhanced public life, not only in Scotland but in the United Kingdom.

Samuel Laird Galbraith, neurosurgeon and politician: born 18 October 1945; consultant in neurosurgery, Great Glasgow Health Board 1978-87; MP for Strathkelvin and Bearsden 1987-2001; Parliamentary Under-Secretary, Scottish Office 1997-99; MSP 1999-2001, Education Minister 1999-2000, Environment Minister 2000-02; married 1987 Nicola (three daughters); died 18 August 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies