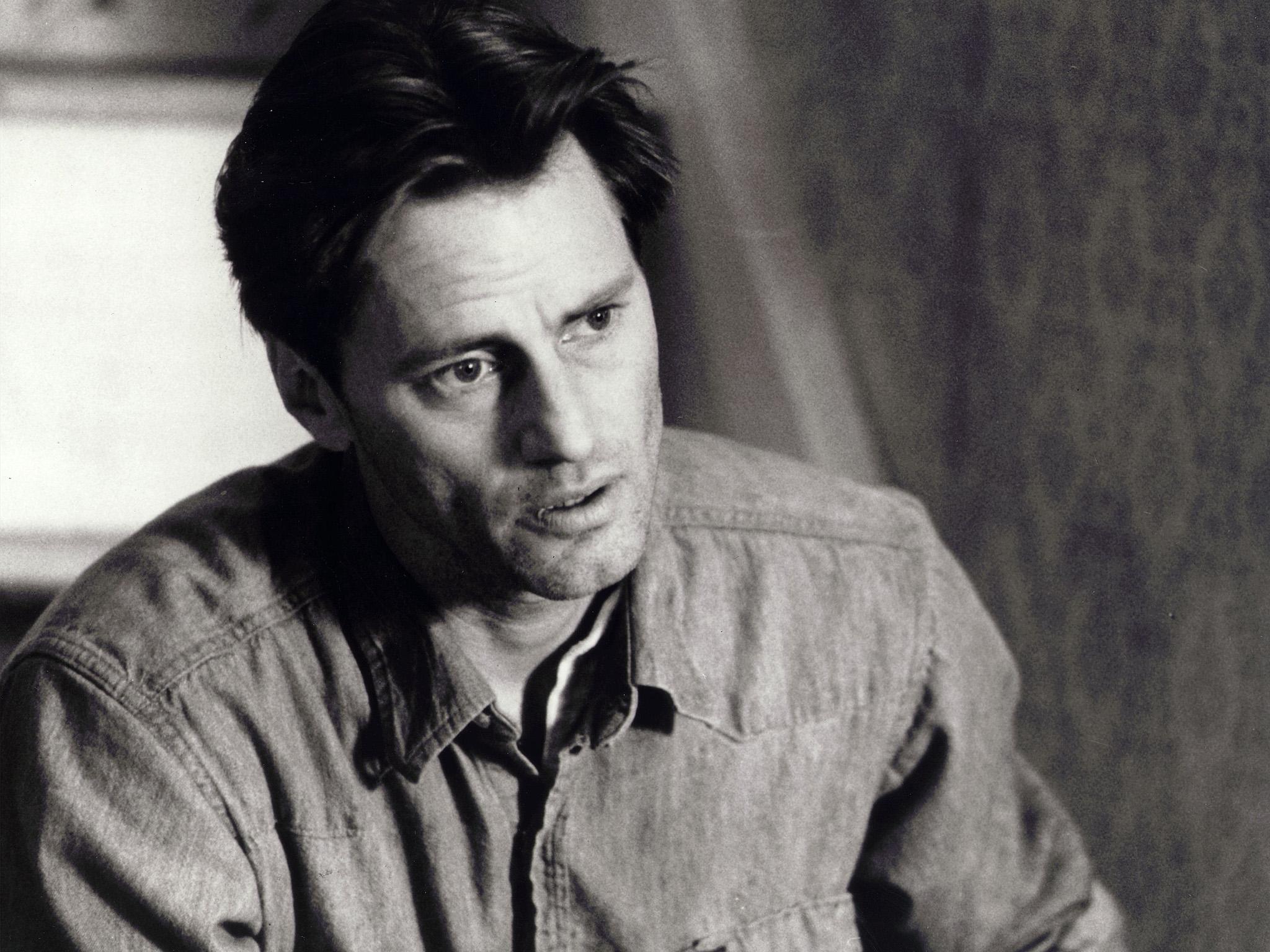

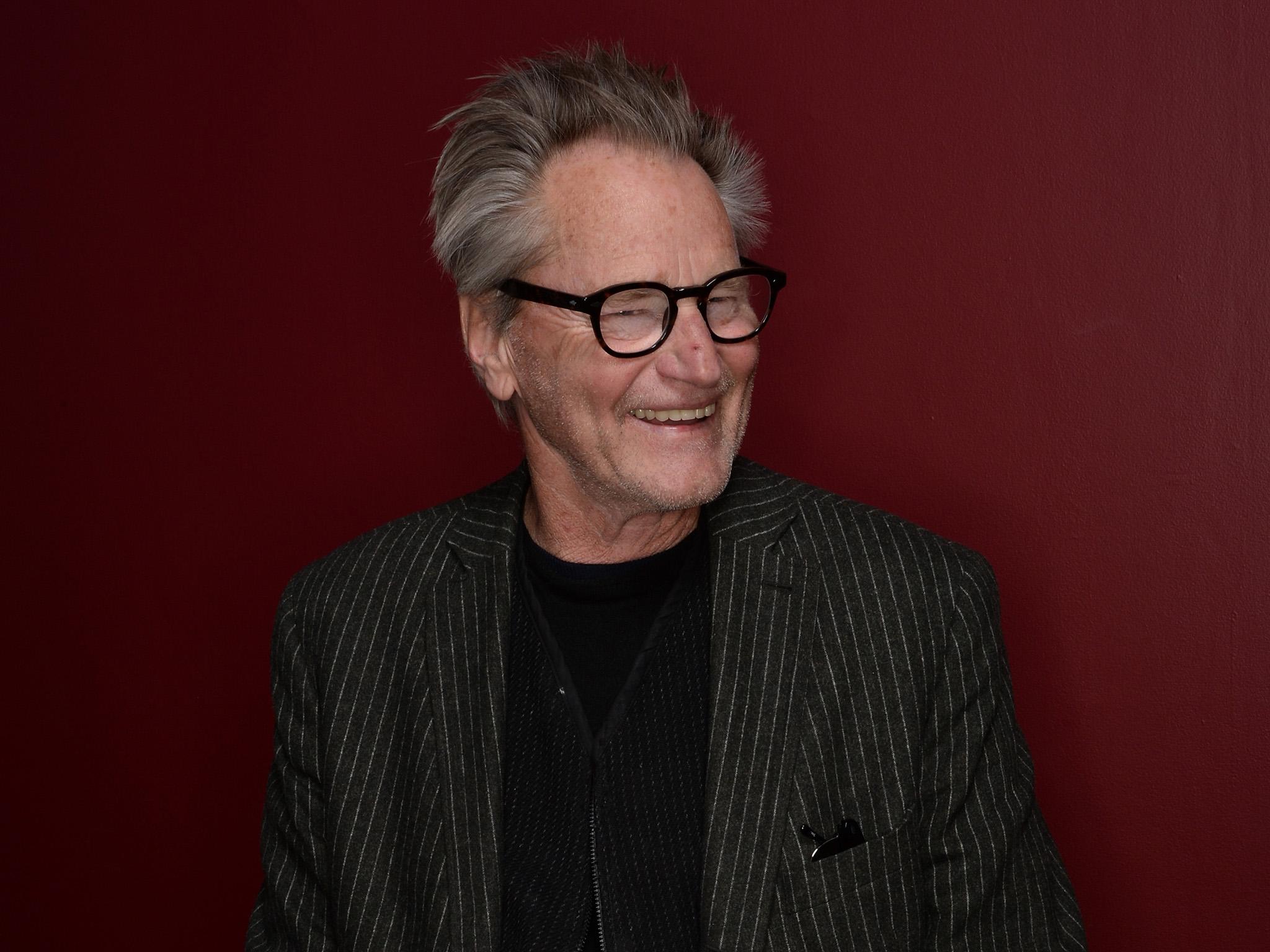

Sam Shepard: The Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright who was also an Oscar-nominated film star

Shepard always regarded Hollywood stardom warily, but he became a major crossover celebrity

Sam Shepard, who has died of Lou Gehrig’s disease aged 73, was an experimentalist cowboy-style poet who became one of the most significant American playwrights of the 20th century – honoured with the 1979 Pulitzer Prize for drama for his play Buried Child and with an Oscar nomination for his acting role as aviator Chuck Yeager in the 1983 film The Right Stuff.

Shepard came of age writing poetry and plays in the 1960s as alternative experimentation transformed the theatre scene. As a playwright, he created an original, influential tone fusing rock-and-roll spirit, Tennessee Williams-style brutal lyricism and a 1960s radical attack on realism.

He became one of the most inimitable voices of the American stage, yet outside theatre circles Shepard was perhaps more widely known for his rugged good looks and understated magnetism on the movie screen.

Many filmgoers remembered him as the crusty Yeager in the film adaptation of Tom Wolfe’s book, as Diane Keaton’s love interest in Baby Boom (1987), and as the brooding Eddie opposite Kim Basinger’s tough May in the 1985 Robert Altman film (of Shepard’s 1983 play) Fool for Love.

He directed two films, including Far North (1988), starring his long-time romantic partner Jessica Lange. They became a couple after appearing together in Lange’s star vehicle Frances in 1982. Previously, Shepard had been married to actress O-Lan Jones.

In 1984, the year he and Jones divorced, Shepard starred with Lange as a struggling farming couple in the film Country, cementing an image of the two of them as noble outsider celebrities. Famously, they lived out of the showbiz orbit in Virginia farm country near Charlottesville, Virginia. They never married and split (characteristically under the radar) almost a decade ago.

Shepard always regarded Hollywood stardom warily, but he became a major crossover celebrity, showing up on lists of America’s Sexiest Men. “Sam was so hot in Resurrection,’” his then-wife Jones later said of his 1980 film with Ellen Burstyn, “that I wrote him a filthy fan letter.”

His early movie credits included a leading role as a farmer in the nearly wordless Terrence Malick film Days of Heaven (1978). He also played the husband of Dolly Parton’s character in Steel Magnolias (1989) and appeared in Black Hawk Down (2001), about the 1993 US raid in Mogadishu, Somalia. More recently, Shepard played the patriarch in the film of Tracy Letts’s Pulitzer-winning August: Osage County (2013).

“[He] has a quality that is so rare now – you don’t see it in the streets much, let alone in the movies – a kind of bygone quality of the Forties, when guys could wear leather jackets and be laconic and still say a lot without verbally saying anything,” Philip Kaufman, director of The Right Stuff, told Rolling Stone.

As a writer, Shepard produced dramas that were poetic, mythical and often highly showy for actors who were tasked with being introspective and combustible. He explored the intersections of an unruly American West and the deep complexities of the fracturing American family, plagued by ghostly fathers and diminished husbands.

“Shepard is a playwright of the American frontier,” the critic Mel Gussow wrote in 1979, “but his plays generally take place in confined, even claustrophobic, rooms. These plays ... form an abundant body of work, one of the most sizeable and tantalising in the American theatre.”

His best-known plays were packed with physical bouts and lyrical, sometimes inscrutable monologues. The visceral force and intriguing subtext of his dramas made him a staple on the country’s stages through the 1970s and well into the 1990s.

Shepard’s output, and his standing as a pivotal theatrical force, declined in the new century, though he continued to act, direct and write. His 2004 The God of Hell took aim at US policy on torture, with a mysterious governmental agent sending electric current through a suspect as American flags proliferated on the stage. The same year he acted in Caryl Churchill’s A Number, a chilling script on cloning. That appearance broke his decades-long absence from the New York stage.

Shepard’s take on the Oedipus myth, A Particle of Dread, made its 2013 debut in Northern Ireland, with Stephen Rea in the leading role. In 2016 he slightly reworked the script of Buried Child for a revival with Ed Harris and Amy Madigan.

Samuel Shepard Rogers III was born in Fort Sheridan, Illinois, in 1943. In his youth he was called Steve, but he eventually rechristened himself Sam Shepard. His father’s army career took the family across the country before they settled on a farm in California, where they cultivated avocados and where Shepard seemed to forge his Western identity. He was deeply affected by the experience of watching servicemen – his earliest models of masculinity – flounder as they re-entered suburbia after fighting in the Second World War.

“They had no role anymore,” he told The Washington Post in 1988. “Their role was to be a soldier. How can you compare life in the suburbs to life in a fighter jet? You can’t. But the women were thinking everything was hunky-dory, and all of a sudden they turned around and the men were alcoholic schizophrenics.” Asked if he was referring to his father, he replied: “Of course.”

Shepard briefly studied agriculture before dedicating himself to the theatre. He acted with a small religious troupe before striking out for New York, where he got a job as a busboy at the Village Gate, a cabaret where Ralph Cook, the founder of the off-off-Broadway Theatre Genesis, was head waiter. Shepard credited Cook with producing his first works. “It was just amazing suddenly to have actors, an audience,” Shepard told The New York Times in 2014. “And kind of embarrassing, like listening to your own voice on a tape.”

Shepard honed his craft writing at a furious rate during the 1960s, a decade when he created more than a dozen works that would be staged at such off-off-Broadway fixtures as Caffe Cino and La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. His first play, which premiered in Manhattan’s Bowery in 1964, was called Cowboys.

Shepard – the recipient of numerous fringe theatre awards – did not have a major production on Broadway until a 1996 revival of Buried Child, the family slugfest laden with such royal symbols as a trucker’s cap as a crown when a son wrests control from his father of an intensely dysfunctional, run-down hovel. A ruined, lifeless field out back had formerly yielded abundant harvests; the image led to interpretations of a crumbling American Dream, though Shepard was only occasionally an overtly topical writer.

His predisposition to plumb psychological depths, blurring past and present in often-barren country, could also be seen in his A Lie of the Mind, another family meltdown, this one climaxing with a main character wrapping himself in a US flag. The drama represented the peak of Shepard’s theatrical rise: the four-hour epic featured Amanda Plummer as the battered Beth and Harvey Keitel as the remorseful husband, Jake, in the 1985 premiere that the playwright directed himself.

“Once the author reaches his final curtain – a domestic tableau of familial and romantic love lost and found, as eternal as a homecoming in a John Ford western – our vision has widened beyond both brothers, their phantom father and Beth to take in a larger landscape,” Frank Rich wrote in a New York Times review of the show, which featured live music by the Red Clay Ramblers.

Shepard, a guitarist and drummer, had a notable affair with musician Patti Smith during his marriage to Jones, whom he wed in 1969. In 1971 he and Smith wrote and performed a play with music, Cowboy Mouth. Smith wrote the forward to Shepard’s 2017 novel, The One Inside, featuring a hero Smith described as “him, sort of him, not him at all”.

Shepard wrote prodigiously though the 1970s, living in London with Jones and pursuing a rock-and-roll career for the first part of the decade while churning out non-realistic works.

After Buried Child, the explosively comic True West cemented Shepard’s new popularity when Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre Company produced it with the young John Malkovich and Gary Sinise in a show that transferred to New York. In 2000 Philip Seymour Hoffman and John C Reilly alternated as the two brothers, with both actors earning Tony nominations for their performances.

Shepard’s survivors include a son from Jones, Jesse; two children from Lange, Hannah and Walker; and two sisters.

At times, his legacy seemed at odds with itself – the matinee-idol looks competing with his deep unease about masculinity in American culture.

“There’s some hidden, deeply rooted thing in the Anglo male American that has to do with inferiority, that has to do with not being a man, and always, continually having to act out some idea of manhood that invariably is violent,” he told The New York Times in 1984. “This sense of failure runs very deep – maybe it has to do with the frontier being systematically taken away, with the guilt of having gotten this country by wiping out a native race of people, with the whole Protestant work ethic. I can’t put my finger on it, but it’s the source of a lot of intrigue for me.”

Sam Shepard, playwright and actor, born 5 November 1943, died 27 July 2017

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks