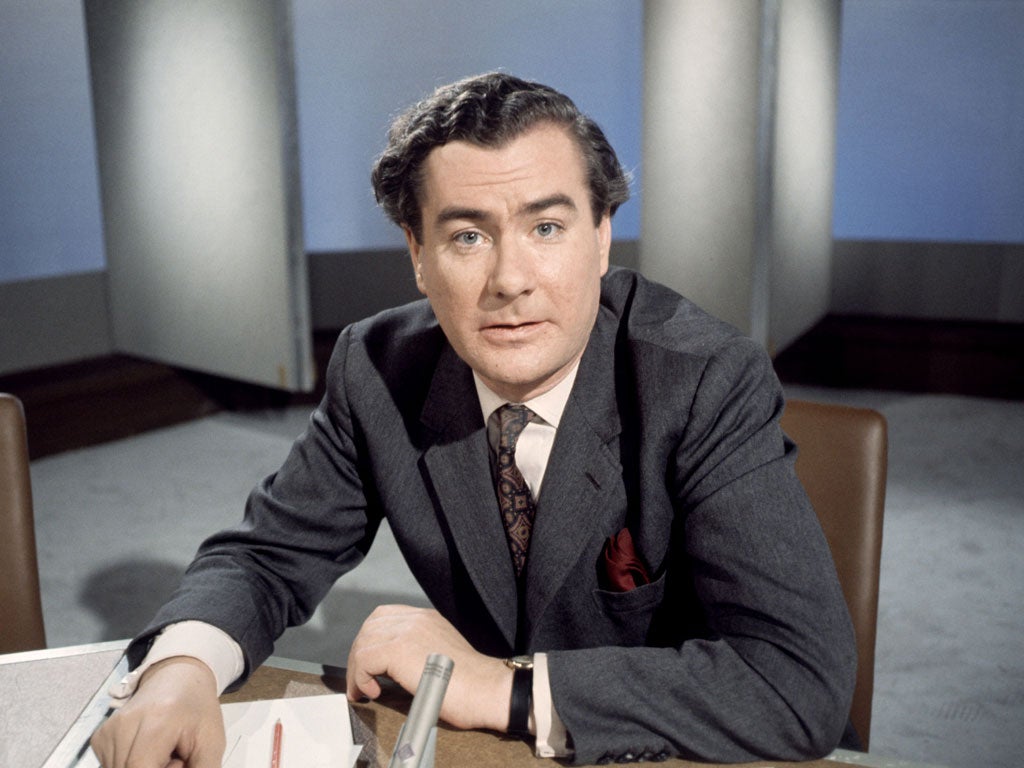

Sir Alastair Burnet Journalist and broadcaster who transformed 'The Economist' and created 'News at Ten'

Preparation was all: 'Homework, homework, homework,' he would tell Alastair Stewart

Sir Alastair Burnet, who has died at the age of 84, was one of the most distinguished British journalists of the past 50 years and one of the few to be equally at home in an editorial chair as in the television studio. During his 10 years as editor of The Economist he transformed the magazine from a semi-academic publication into a genuinely intelligent "news and opinion weekly". In doing so he showed notable courage in facing up to the publication's overbearing chairman Lord Geoffrey Crowther, and to the company – then the Financial News/Financial Times Group, now Pearson – which owned half the shares in the magazine. At the same time he forced the reluctant barons of Independent Television to create a half-hour News at Ten from what had previously been merely a 10-minute slot.

For nearly 30 years he was ITN's anchorman for major events, including no fewer than six general elections. He was an unrivalled presenter, a legend for his professionalism, his psephological expertise and his authoritative ad-libbing, which none of his successors has ever matched. He was immensely loyal to the teams of people with whom he worked and they reciprocated his loyalty, but his social life was largely limited to the racecourse, where he was a regular visitor, and not always lucky punter – and later director of United Racecourse Holdings. Unfortunately in later life his sturdily conservative political beliefs, notably his deep respect for the Royal Family, and above all his deep unionism, which led to an equally profound loathing of any idea of Scottish devolution, made him an easy target for satirists and led the public to forget his real stature and achievements.

Alastair Burnet was born in Sheffield in 1928 of a Scottish engineer father who died young. After schooling at the Leys School, Cambridge, he studied history at Worcester College, Oxford, where his papers on Scottish history were considered remarkable. In 1951, at a time when training away from Fleet Street was considered obligatory for a would-be journalist, he joined the Glasgow Herald as a leader writer.

The first recognition of his qualities came from selection as a Commonwealth Fellow, funded by the Harkness Foundation, a distinction shared with only a handful of other outstanding journalists. The resulting stay in the United States provided him with a depth of knowledge of American politics as profound as his understanding of the British political scene. The Fellowship, combined with a piece he wrote for The Economist, gained him a job on the magazine in 1958. But he felt lonely and unappreciated, and in 1963 went to Independent Television News as political editor, a bold step at a time when television, particularly "commercial" television, was rather looked down on by the chattering classes.

But two years later at the age of 38 he was chosen to be editor of The Economist. There was a precedent: Geoffrey Crowther, the founder of the modern Economist, had been appointed in 1938 when he was only 30. Burnet was lucky to get the job after a confused appointment process which nearly led to the appointment of Roy Jenkins. But Crowther, who as chairman still dominated the publication, believed that "Burnet has all the best qualities of a Scot", and had already thought of him as a possible editor when he left for ITN.

During the 17 years of his editorship Crowther had established the basic format of the magazine, its division into political and business sections, and above all the contrast between the leading articles, which made it something of a "viewspaper", and the pages devoted to news and analysis. As he once put it, he realised that "the great difficulty for The Economist is always to be sensible without being heavy, to be lively without being silly, to be original without being eccentric."

Burnet fitted the bill admirably. His style was described as "punchy direct and challenging... he was driven by a desire to persuade as many people as possible to read The Economist: everything else took second place to that... he was a news man rather than an opinion man." He didn't undermine the intellectual seriousness of the magazine but superimposed a new journalistic alertness and informality of style, even encouraging investigative journalism. As one admirer, Harold Macmillan, put it, "Bagehot" – the legendary 19th century editor – "would have approved. It suits the age... it's practical, it's modern, it's objective, it's up to date."

This was most obvious with the appearance with the introduction of lively covers and insistence on "a pic a page". As a result circulation started to climb even further – it had been a mere 10,000 before the war and 55,000 in 1956 but was over 100,000 when he left in 1974.

Politically his impact was just as great. Where the magazine had advised its readers to vote for Labour in 1964, under Burnet it became firmly Tory, as well as being equally firmly as enthusiastic as Edward Heath over Britain's entry into the then Common Market. Aware that he wasn't as intellectually distinguished as his predecessors, Burnet relied heavily on the foreign editor, Brian Beedham – a stalwart supporter of America's policy in Vietnam – and above all on Norman Macrae, the deputy editor and all-round guru. But one of his greatest gifts was his flair and courage in his recruitment policy – his investment editor had been an out-of-work film editor – and his recruits also included his successor, Andrew Knight, and Sarah, later Baroness, Hogg.

Burnet himself could even be called an early Thatcherite as he became a staunch supporter of the Thatcherite Institute of Economic Affairs. He explained how they were: "polite, even courteous, plainly intelligent fellows who enjoyed an argument... The intellectual concussion caused by the revolution conducted by Ralph Harris and Arthur Seldon from 1957 onwards, upon the body politic and economic was cumulative and, eventually, decisive. Policies that were deemed to be politically impossible and unpopular by politicians, civil servants, captains of industry and the trade unions were discovered to be practical, popular and successful. Even television and the newspapers began to get the idea... Success has many fathers, but none have better deserved the recognition and acclaim than the founding fathers of the IEA, who did the work. They did the fighting. They took the risks. They had the solutions."

At the same time as editing The Economist Burnet continued to broadcast. He anchored ITN's coverage of the 1964, 1966 and 1970 general elections and the Apollo 11 moon landing in 1969. In 1967 Burnet forced the reluctant barons of Independent Television to add a full 20 minutes – "over the body of Lew Grade", as Burnet put it at the time – to what had been merely a 10-minute bulletin. This was a very risky business, since the ITV barons assumed that the experiment would be quietly dropped after a 12-week experimental period. Amazingly he combined his editorship with a role as one of the main newscasters for News at Ten between 1967 and 1973.

After leaving The Economist in 1974 Burnet pursued his dual career as editor and television presenter. He had an unhappy couple of years editing the Daily Express, then still considered a reputable paper, hoping to restore some of the prestige it had lost in the decade following the death of Lord Beaverbrook in 1964. But without a loyal team behind him he couldn't renew the paper to his liking so in 1976 he resigned, refusing to accept any pay-off. At the same time he continued working for television, anchoring the February and October 1974 general election programmes for the BBC, and also working on Panorama.

But during the 15 years after leaving the Express he became the ever-reliable senior anchor man for ITN until 1991, the much-respected leader of a close-knit team and one of television's most complete professionals. He was the main single newscaster for the newly-launched News at 5.45 from 1976–80, returning to News at Ten as one of its main presenters until his final broadcast, on 29 August 1991, retiring at the same time as Sir David Nicholas, ITN's long-serving editor-in-chief.

Burnet anchored the 1979, 1983 and 1987 general election programmes as well as major events like the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer in 1981. As Sir David Nicholas, Editor and then Chairman of ITN, put it, "he was key to the programme's stature. A complete anchorman, he combined an amazing historical memory with a great gift for comparisons in a couple of sentences... Even after seven or eight hours during a general election he could provide a fluent two-minute summary. Not surprisingly he received three coveted Richard Dimbleby Awards

Alastair Stewart, one of his successors, summed up his qualities: "He impressed upon those working with him how important it was to go into a studio prepared. 'Homework, homework, homework,' he would say, and that's never left me. I used to always carry notes with me into the studio so that I could look up anything that I couldn't remember. He told me that one day I would walk into the studio with only one piece of paper. I asked him what would be on the paper and he said, 'For me, at budget time it's always the name of the horse I've backed in the Cheltenham Cup. Whatever it is for you, dear boy, will be for you to decide.'"

Much of his appeal lay in the fact that he wasn't a man who ever stood on ceremony. In meetings he would say, "This isn't something that plain folk would be remotely interested in," and insisted the news lead on what the "plain folk" would be talking about the next day. However, he wasn't frightened of leading on heavyweight stories because his brilliant writing skills would bring the story alive. He had the most phenomenal comprehensive knowledge base and encyclopedic memory – not just for the great events in history but for oddities, too. He would read out a football result – "Partick Thistle 3, Clyde 1" and then say: "That's the first time they've scored in three games."

Unfortunately for his reputation, in the mid-1980s Burnet presented several documentaries about the Prince and Princess of Wales which were too respectful for contemporary taste and resulted in some tasteless appearances as a puppet in Spitting Image. He also attracted criticism as an independent National Director of Times Newspapers from 1982 to 2002. There, he and his colleagues were able to prevent Rupert Murdoch from appointing any unsuitable figures to edit The Times and enabled the editors of both The Times and The Sunday Times to retain a surprising degree of independence from their proprietor's opinions.

James William Alexander Burnet, journalist and broadcaster: born Sheffield 12 July 1928; Kt 1984; married 1958 Maureen Sinclair; died London 20 July 2012.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks