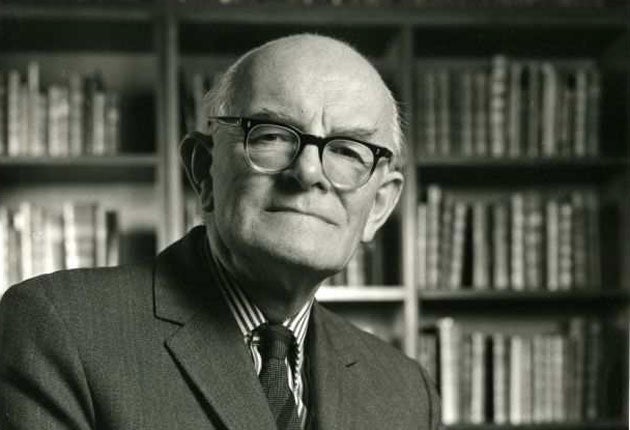

Vivian Ridler: Printer to Oxford University from 1958 to 1978 and founder of the Perpetua Press

Vivian Ridler was the printer's printer, master of "the whole art of printing". He began as a boy and ended his career as Printer to Oxford University, the last great holder of that office. But beside his distinguished official career, he also ran a private press, whose work, a model of typographic design, included original work, not least that of his wife, the poet Anne Ridler.

He was born, in 1913, in Cardiff, but when he was five his father became superintendent of Avonmouth Docks. Crossing the Severn took him to Bristol Grammar School, but long before that he had become a printer. Seeing an advertisement for an Adana table press, he persuaded his parents to buy it. With it came a pound of type, enough for cards and small leaflets.

When he went to school he met his lifelong friend David Bland, whose father's vicarage provided more space for the press. A visit to the Bristol printer John Wright produced more type. Thus augmented, they printed a philatelic magazine that they wrote themselves, altering the text if they ran out of letters. The result was oddly spotty, because the type from Wright was different from that supplied with the Adana. From this he learned two lessons that underlie all his work: the need for the right type for any job, and "the interdependence of author and printer".

Leaving school in 1931, he was apprenticed to E.S. & A. Robinson,the biggest printing firm in Bristol. There he had the basic groundingin composition (by machine, not hand) and printing, as well as the waysof compositors and printers, before moving on to the counting-house and management.

But the press at the vicarage kept busy; it acquired new and lively clients, Douglas Cleverdon, Eric Walter White and James Stevens Cox. In Cleverdon's bookshop Ridler met Eric Gill, whose Perpetua type gave the press its name. Fifteen Old Nursery Rhymes, with illustrations hand-coloured by Biddy Darlow, was chosen as one of the "50 Best Books of the Year" by the First Edition Club in 1935. As the Perpetua Press grew, Robinson's obligingly provided a larger press, which overstretched the power supply so that the street lights went dim.

In 1936, John Johnson, then Printer to Oxford University, lectured at Bristol on jobbing printing (his collection is now at the Bodleian Library). Bland and Ridler went to the lecture; afterwards they asked if they might print it and showed him their work. Nothing came of this, but that winter Johnson wrote to Ridler, offering him a job as his assistant.

Astonished but delighted, Ridler went to Oxford. He got on well with Johnson, but found his bullying treatment of others hard to bear. Bland had gone to Faber & Faber, where Anne Bradby, niece of Sir Humphrey Milford, the Oxford University Press Publisher in London, was also working as T.S. Eliot's secretary; visiting his old friend, Ridler met her and they fell in love. When their engagement was announced, Ridler was immediately dismissed by Johnson, convinced that he must now be a spy reporting to his rival in London.

They married in 1938, none the less, and fortunately Ridler met Theodore Besterman, the prince of bibliographers, who had set up the Bunhill Press, overlooking Bunhill Fields, to print his own and other works. Besterman asked him to be its manager, and he and Anne set up house in Clerkenwell. Her first Poems were printed at the Bunhill Press for the Oxford University Press.

They stayed on when the Second World War broke out. Next summer the blitz fell heavily on the City; after a particularly bad raid one night Ridler decided to go and see how the Press was. On the way, he saw a pile of paper in the gutter, stooped to pick it up and found it was a batch of the jackets for Anne's book that they had just finished printing. Fearing the worst he hurried on, to find that the press had been blown to pieces.

On the way home, they were stopped by a warden, who said itwas dangerous to go on. He expostulated, "But we live here", and they went on, passing already damaged houses. Going upstairs, there was another whoosh and bang and the whole house seemed to rise and settle. They reached the top floor where they lived, and opened the door to find everything in place, but dark. They looked up and could see the stars; all the slates from the roof were spread over bed and floor.

After that they moved to the country, and a fortnight later Ridlerwas called up and went into the RAF. He became an intelligence officer, first in Orkney and then in Nigeria, at Lagos and (more happily) at Kano. When the war ended, he was posted to Germany to supervise de-militarisation in the Ruhr; he found the devastation painful and orders not to "fraternise" absurd – how could you talk to Germans all day and not get to like at least some of them?

Demobilised, he returned to London, becoming lecturer on typography at the Royal College of Art and earning a living as a freelance designer for Lund Humphries and others. He became art editor of Contact, the magazine founded by George Weidenfeld before he set up his own firm. He and Anne were not rich, but happy, with visits to plays and concerts in a London still shabby after the war.

This came to an end in 1948 when Charles Batey, who had succeeded John Johnson at Oxford, invited Ridler to return as Works Manager. He was at first reluctant, with unhappy memories of earlier days there, but Batey was insistent and he eventually agreed; only later did he reflect that the post carried a pension and he would have been mad to turn it down. Later he became Assistant Printer, succeeding Batey as Printer in 1958.

By now he had some substantial achievements to show, notably the Bible he designed, on which the Queen swore the Coronation oath in 1953, the New English Bible in 1961 and a facsimile of The Waste Land that needed two-colour printing to elucidate.

The cares of office were not all so agreeable. I had asked if there were an opening for a beginner at the Press: "How do you think I spend my time?" he asked; dealing with the day's business and then designing books, I suggested. "No, I'll tell you. Half my time is spent arguing with unions and the other half negotiating the purchase of machinery with banks. If you want to design books, go to London and work for a publisher". This was not wholly true: he still found time to design books and jackets, to look for and introduce new machines and working methods and demand and get the highest standards of quality.

In 1968-9 he became President of the British Federation of MasterPrinters, and was appointed CBE in 1971. He retired in 1978, the year in which the Press celebrated thequincentenary of printing in Oxford. There was an exhibition of his work in the Divinity School at the Bodleian, and St Edmund Hall – which had made him a professorial fellow in 1966 – elected him to an emeritus fellowship. But his professional life was far from over. The Perpetua Press was revived in the comfortable stone house in Stanley Road where he and Anne continued to live. Over the next 20 years, some 30 books, many if not all set by hand and printed by Ridler, were printed and published

He began with three books of Anne Ridler's poems. Her edition of The Poems of William Austin (1983) drew praise in the TLS for both editor and printer. In 1984 he was joined by Hugo Brunner, then at the Hogarth Press, who brought the first of several books by George Mackay Brown, reviving memories of Orkney. Poetry ancient and modern, tributes to Isaiah Berlin and Aung San Suu Kyi, Anne Ridler's opera libretti, made up a diverse list. The longest book, too long for Ridler to print himself, was A Victorian Family Postbag, the Bradbys' letters, published to celebrate the golden wedding of Anne and Vivian in 1988.

Early bald, Ridler had, like James Spedding, a noble dome. There was always a glint of humour behind his spectacles, and he had a vivid turnof speech. Active and precise, his movements at work were a joy to watch. He set others the same high standards as himself, but was gentle with failure. He made the University Press a happy place to work in, even in difficult times. Stoical when the university printing house closed in 1989 after three hundred years, he found his stoicism tried to the utmost when Anne died in 2001, ending over 60 years of happy work, by which he as well as she will be remembered.

Christmas and Vivian Ridler were inseparable. A great Father Christmas at countless Ridler family Christmases, he was a notable printerof Christmas cards, with texts by, or chosen by, his wife. Last month, incelebration of his 95th birthday, the Bodleian Library held an exhibition of some of the many cards from fellow artists and printers that the Ridlers had received in return. Vivian Ridler was there at the opening, surrounded by old friends – and in fine form and voice, even if limited finally to wheelchair travel.

Vivian Hughes Ridler, printer: born Cardiff 2 October 1913; Works Manager, University Press, Oxford 1948-49, Assistant Printer 1949-58, Printer to Oxford University 1958-78; Professorial Fellow, St Edmund Hall 1966-78 (Emeritus); President, British Federation of Master Printers 1968-69; CBE 1971; married 1938 Anne Bradby (died 2001; two sons, two daughters); died Oxford 11 January 2009.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments