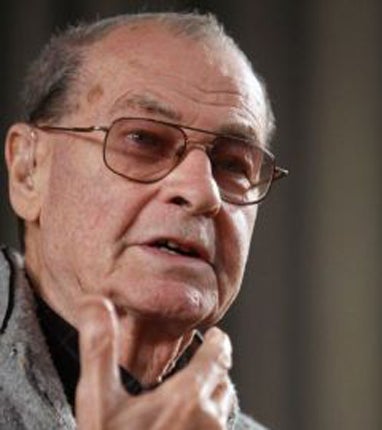

Vladimir Motyl: Film director who battled for all his career against the Soviet authorities

Like many Soviet artists, Vladimir Motyl's star waxed and waned, but with White Sun of the Desert the film director created a bullet-proof hit, popular and, ultimately, politically acceptable.

In the 1960s "Red Westerns" or "Easterns" – films based on Hollywood westerns but set in the Eastern bloc – became very popular. Motyl's contribution was 1969's White Sun of the Desert [Beloe solntse pustyni]. It was a troubled shoot. Even before Motyl signed up, it had been rejected by a series of increasingly unlikely directors, culminating in Tarkovsky. Motyl considered turning it down himself, hoping to make a film about the 1825 Decembrist uprising, but director and studio head Grigori Chukhrai warned him that it could be his last chance.

On-set, Motyl's improvisations and departures from the script led to accusations of incompetence and at least once production was closed down. At times it was so under-funded that actors playing soldiers donned niqabs to become members of the harem. When equipment was stolen, a local crime boss offered to recover it in return for a role.

The misadventures of a demobbed soldier who is persuaded to look after the harem of an escaped Basmachi guerrilla proved wildly popular. It even became traditional for cosmonauts to watch it before blast-off. It supplied wry observations and aphorisms that still pepper Russian conversation: "The east is a delicate matter" covers anything that might be best left alone. However, it was not officially recognised at the time and was only awarded a state prize in 1997.

When Motyl was three, his father, a Jewish-Polish engineer, was arrested and sent to the notorious Solovki camp where the following year he died. Several other relatives suffered similarly; Vladimir and his mother were exiled to the northern Urals, where she taught at a school for juvenile delinquents.

Motyl determined to be a director early: at school he subscribed to Soviet Film and mounted plays. But he failed to get into film school (he claimed he was distracted by his first love affair) and went to the Sverdlovsk Theatrical Institute instead. After graduating in 1948, he worked in theatres across the Urals and Siberia. In 1955 he became head of the Sverdlovsk Young Spectators' Theatre and two years later was heading the Sverdlovsk Film Studio.

In 1963 he directed his first film, the Tadjik-based Children of the Pamirs [Deti Pamira]. He was not first choice, and it glorified the regime that had killed his father. But it was a way into the industry. He salved his conscience by making the "rebel" child who is condemned in the script a more sympathetic and heroic figure, and in the process created a prize-winning popular success.

In 1967 he made the wartime comedy-romance Zhenya, Zhenechka and "Katyusha", which punningly referenced the popular song and Soviet rocket-launchers. Even 22 years after the Great Patriotic War, the Army Political Department condemned its light tone as "disrespectful". Nevertheless it was accepted for distribution, though Goskino's chairman vowed that it would be Motyl's last film. But he made a triumphant return with White Sun.

Despite that film's success , Motyl's career stalled for several years. Unenthused by an "irrelevant" Decembrist story, the studio offered a minimal budget in the hope he would reject it. But, convinced of its importance, he accepted, taking such care over historical accuracy that he gave cast members banned books for reference. The Captivating Star of Happiness (1975) [Zvezda plentilnogo Schastya] takes its title from Pushkin, and follows the story through the to Decembrists' exile, voluntarily accompanied by their wives. It is dedicated to "the women of Russia".

Though it could hardly rival its predecessor it was still popular. But from then on, his success would diminish. He had a reputation for being difficult: he was uncompromising in his work and, having stood aloof from state organisations, he was banned from foreign delegations. The 1980 Ostrovsky adaptation The Forest marked a low-point, and was banned until 1988. But Motyl had fought back to make The Incredible Bet (1984), a concatenation of Chekhov stories for TV.

After perestroika, Motyl repaired enough bridges to join the board of the Cinematographers' Union and become Secretary of the Moscow union, continuing to pick up state prizes. Aside from a couple of features, he wrote scripts and produced. In 2004 he started Crimson Snow, a romance set in the run-up to the Revolution. Though it was hardly autobiographical he described it as being about his father, as Captivating Star of Happiness had been about his mother. In a 40-year career it was his 10th feature. The production dragged on: completed last year, it has yet to be released.

John Riley

Vladimir Yakovlevich Motyl, film director: born Lepel, Belarussia 26 June 1927; married Ludmilla Podarueva (died 2008; one daughter); died 21 February 2010.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks