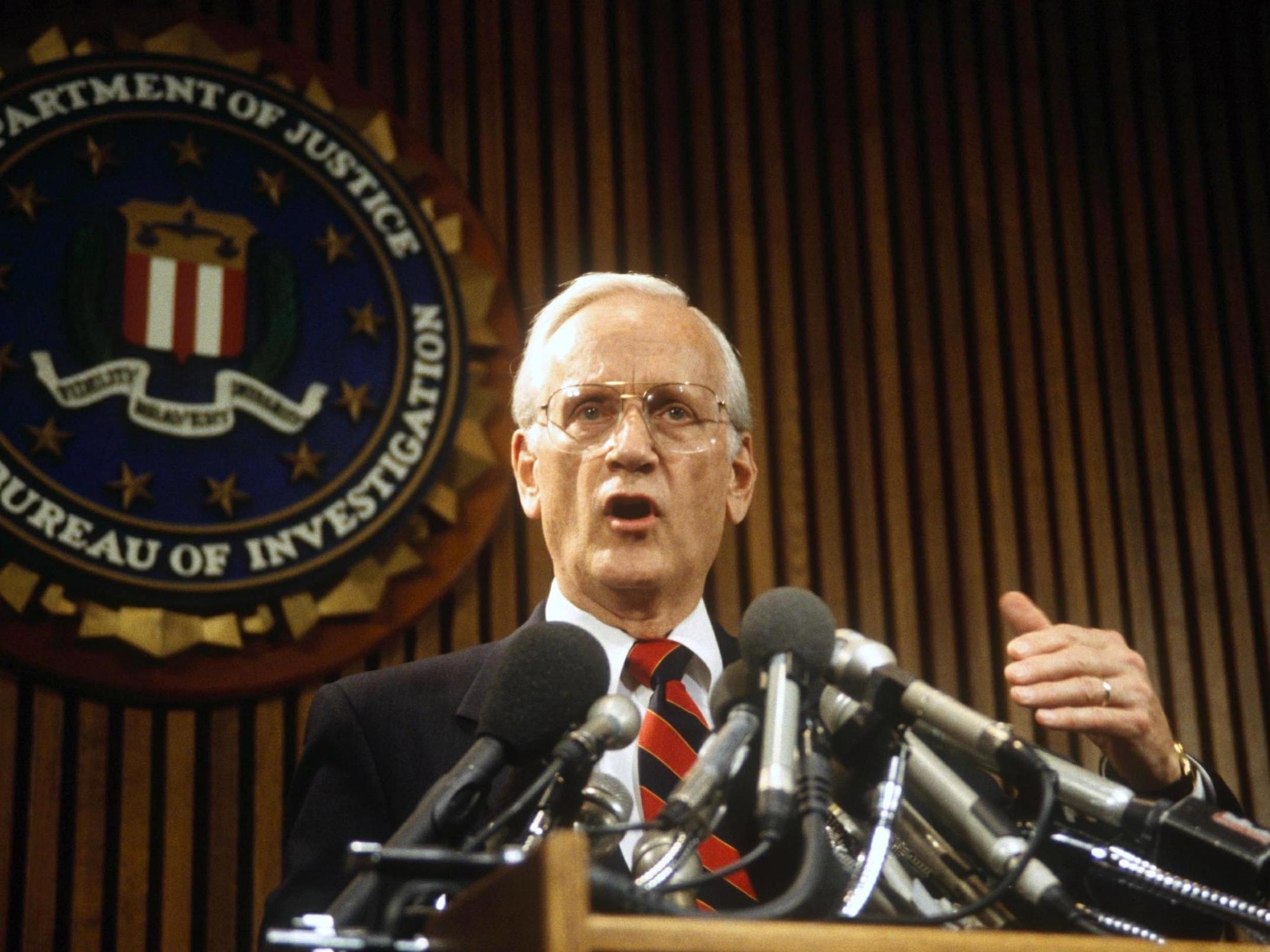

William Sessions: FBI director who battled agency’s old guard

He made his mark as a strict but principled federal prosecutor and judge before Ronald Reagan appointed him as bureau chief

William Sessions was a straight-arrow director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation from 1987 to 1993 who faced down the agency’s old-boy network to start bringing in more black, Hispanic and female agents, only to be fired for petty financial misconduct.

He died on 12 June at his son’s home in San Antonio. He was 90. The cause was complications of congestive heart ailment, said his daughter, Sara Sessions Naughton.

Sessions bitterly fought a Justice Department report that accused him of abusing the perks of his job – avoiding taxes on his use of an FBI limousine and contriving work-related trips to meet relatives, among alleged violations. He refused to resign and ultimately was dismissed by president Bill Clinton in July 1993.

Proclaiming his innocence, he and his fiercely protective wife, Alice, blamed the report on disgruntled agents, saying they were unhappy with Sessions’s independence and his shake-up of the FBI’s traditional order created under J Edgar Hoover, who had ruled the agency from 1924 until his death in 1972.

In addition to his own internal struggles with the agency, Sessions weathered sharp public criticism during his tenure for his handling of the fatal Ruby Ridge shootout in Idaho in 1992 and the fiery siege of the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, in 1993.

Only the third Senate-approved director since Hoover – there were several acting directors as well – the austere, teetotaling Sessions made his mark as a strict but principled federal prosecutor and then judge in west Texas before president Ronald Reagan tapped him for the FBI post in November 1987 to succeed William Webster, another federal judge.

In a typically self-effacing quip about his tough-lawman image, Sessions said at the time: “I don’t wear a gun belt. I don’t have any cowboy boots to my name. If I’m a west Texas tough guy, it’s only because we have dealt with difficult problems out here.”

In retirement, even though a supporter of capital punishment, he joined other former judges, as well as civil liberties lawyers and several members of Congress in calling for clemency for two high-profile death row inmates in Texas and Georgia.

In letters and briefs to the US Supreme Court, he argued that the murder trials of the two had been so fundamentally botched, including by the use of questionable police line-up tactics and the participation of unprepared defence lawyers, that the pair should be spared the death penalty.

“When a criminal defendant is forced to pay with his life for his lawyer’s errors, the effectiveness of the criminal justice system as a whole is undermined,” Sessions and others wrote to the high court. One inmate’s sentence was ultimately commuted to life. The other inmate was executed.

Sessions also won lasting public support from Coretta Scott King, the widow of the slain civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr, for his efforts in recruiting and promoting minority agents within the FBI – an agency that had conducted controversial surveillance of King and his organisation under Hoover in the 1960s.

Sessions’s recruitment endeavours were a reaction largely to discrimination lawsuits by black and Hispanic agents and resulted in modest gains during his tenure – the black proportion of agents grew from 4.2 per cent to 5 per cent, for example – a pace he blamed in part on interference by FBI insiders.

William Steele Sessions was born on 27 May 1930, in Fort Smith, Arkansas, the son of a prominent Disciples of Christ minister.

The family, including a daughter, Toveylou, moved about the midwest in the 1930s as the father changed pulpits and achieved notice for writing the God and Country”handbook for the Boy Scouts of America. The future FBI director remained an avid canoeist and mountain climber, and scouting became a tradition across generations in the Sessions family.

At the end of the Second World War, the family moved to Kansas City, Missouri, where Sessions finished high school in 1948. With the outbreak of the Korean War, he enlisted in the air force and became an airborne radar intercept instructor, mustering out as a captain in 1955.

While in the service, he married Alice Lewis, daughter of an offshoot Mormon minister. She died in December 2019. In addition to his daughter, of Weston, Connecticut, survivors include three brothers, Louis Sessions of Dallas, former representative Pete Sessions, R-Texas, of Waco and Mark Sessions of San Antonio; nine grandchildren; and five great-grandchildren. A son, Jonathan, died in infancy.

Sessions and his wife first lived in Waco, Texas, where he studied at Baylor University on the GI Bill and finished an undergraduate degree in 1956 and a law degree in 1958. He entered 10 years of private practice in Waco, then took a job with the Justice Department’s criminal division in Washington in 1969, prosecuting obscenity, voter fraud and draft-evasion cases.

A moderate Republican, he was named US attorney for the Western District of Texas by president Richard Nixon in 1971. Three years later, president Gerald Ford elevated him to judge in the district. He became chief judge in 1980 and held that position until Reagan brought him back to Washington in 1987 to run the FBI.

In the still-insular world of the FBI, Sessions was an outsider, resisted by many in the agency hierarchy. He initiated changes that upset some but encouraged others in and out of the FBI, including his patrons in Congress.

He started an affirmative action program for hiring and promoting more minorities and pushed for higher pay and modernised data-processing equipment.

He defended the FBI’s controversial Library Awareness Program in the late 1980s that encouraged public libraries to report “suspicious” individuals who might be Soviet operatives. But he disciplined six bureau employees who had been involved earlier in extensive surveillance of the Committee in Solidarity With the People of El Salvador and other left-leaning groups opposed to US policy in Latin America.

In the 1992 Ruby Ridge incident, the bureau was criticised in an internal probe for overreacting when an FBI sniper killed unarmed Vicki Weaver and her son in a shootout with an anti-government survivalist group in the northern Idaho wilderness.

Similarly, just before Sessions’s dismissal in 1993, the FBI, along with other federal agencies, was blasted for its handling of the 51-day siege of the Branch Davidian sect’s compound in Waco that ended in an assault and spectacular fire. At the end of the confrontation, 76 people were dead.

The breach between Sessions and the bureau became public earlier, in 1989, when he ordered agents to investigate the Republican-controlled Justice Department’s role in US-backed agricultural loans to Iraq that were diverted to arms purchases, a scandal dubbed Iraqgate by the media.

Shortly after that, the Justice Department started an ethics probe into Sessions’s conduct as director, a tangled process climaxing in January 1993 with a scorching 161-page report issued by attorney general William Barr (who is now in the same role under president Donald Trump), accusing Sessions of gouging the government, frequently for petty gain, and questioning his fitness to serve.

According to the report, he artfully arranged business-related flights on FBI aircraft to visit his daughter and other relatives and dodged tax liability on the use of his official limousine to and from home by keeping an unloaded gun in the trunk to establish an on-duty status – what Barr called “a sham arrangement”.

Most notable was that Barr ordered Sessions to reimburse the government $9,890 for the cost of a decorative wooden fence installed around the director’s Washington home that did not meet the metal security standards that Barr said were required.

Sessions disputed the report’s findings point by point, saying he had cleared many of his actions with FBI lawyers and found the report riddled with errors and false conclusions. He did agree, however, to make partial repayment for the fence.

“This process has been conducted without the barest element of fairness, marked by press leaks calculated to defame me,” he said in a statement. More important, he added, the report accepted accusations, largely without question, by an agent he had fired from his personal security detail.

Alice Sessions took a broader view. In May 1993, she told Texas Monthly magazine that she sensed long before her husband that the old-guard hierarchy of the FBI wanted to isolate and ultimately dump him, and that the Barr report was the vehicle for it.

She was joined in this suspicion by Curt Gentry, a historian and critically acclaimed Hoover biographer who, according to Texas Monthly, sent her a lengthy memo outlining his findings about FBI resistance not only to Sessions, but also to other post-Hoover directors appointed from outside the agency.

Sessions’s mistake, Gentry said, was failing to recognise that he was dealing with a “palace revolt, the attempt of a small cabal, numbering probably no more than a half dozen senior officials, to recapture control of the bureau”.

Except among the Hoover loyalists, Sessions enjoyed a reputation for fairness, political independence and exacting standards, especially from the bench.

“His style is not to bully,” said civil liberties lawyer Maury Maverick Jr, who battled Sessions in draft-resistance cases in the 1970s, “but if you are a crook and stick your neck in a noose, he will hang you and smile like Jesus while he’s doing it.”

William Steele Sessions, FBI director, born 27 May 1930, died 12 June 2020

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks