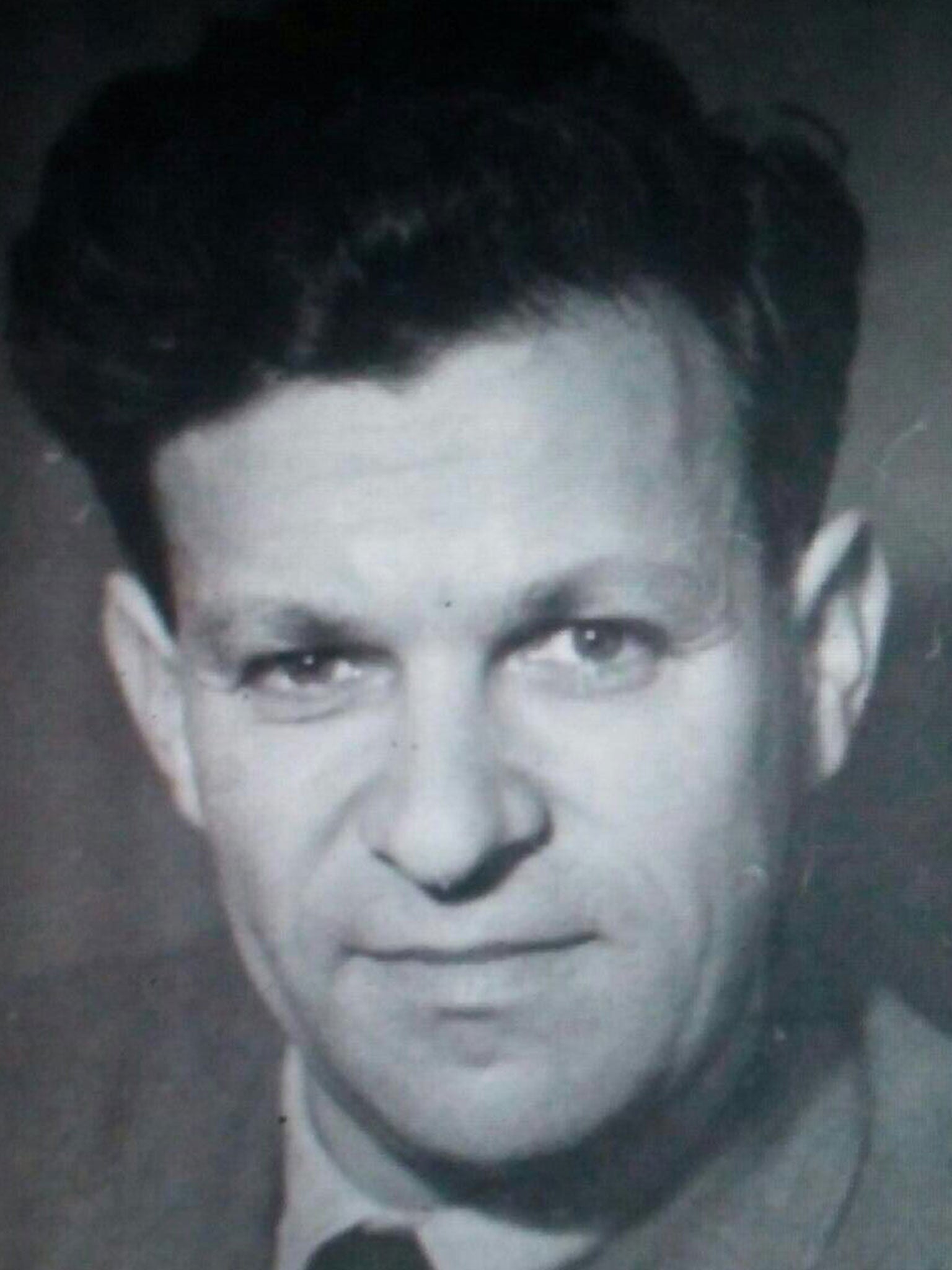

Ezra Levin: Architect who designed the 'Silver Hut' made famous by Sir Edmund Hillary and championed wood as a modern material

The pair used the Hut both as sleeping quarters and as a laboratory for testing the effects of altitude on the human body

The architect Ezra Levin designed the shelter that gave Sir Edmund Hillary's 1961 Himalayan "Silver Hut" expedition its name; he was also a distinguished international authority who advanced the use of wood as a modern engineering material. To this day Levin's distinctive cylindrical, foam-insulated marine plywood Hut is a familiar sight to trekkers who use the base camp, at 14,600ft, of the Indian-run Himalayan Mountaineering Institute at Darjeeling, where the 22ft by 10ft box-sectioned structure was later re-erected.

Hillary originally perched the silver-painted Hut at 19,000ft on the Mingbo Glacier below the summit of the mountain he and his team hoped to climb, Makulu, at 27,790ft the fifth highest in the world. They used the Hut both as sleeping quarters and as a laboratory for testing the effects of altitude on the human body.

Levin, who was introduced to Hillary by a fellow architect and mutual friend, developed the design over six months in consultation with Hillary's scientific officer, Dr Griffith Pugh (obituary, Independent, 27 January 1995). He and Pugh consulted the designer Donald Gomme, originator of the celebrated 1950s G-Plan furniture and of the remarkable wooden frame of the De Havilland Mosquito combat aircraft. They rejected Hillary's initial idea that the hut should be made from wire netting and canvas, though Hillary later claimed that Levin's design had emerged from a sketch he, Hillary, had drawn.

The Hut turned out to be "a wonderful home and workplace," as one expedition member declared. Held by wires from flying away, it proved itself a success that stood out from the expedition's many misfortunes. The climbers, who attempted to climb without extra oxygen, neither found the Yeti, as they had hoped to do, nor conquered Makulu. Hillary had a mild stroke, and others were taken ill with breathing problems. Even when they reached the neighbouring peak of Ama Dablam, at 22,300ft, the Nepalese government objected that they had not obtained permission, and Hillary had to go to Kathmandu to apologise.

With the help of the Hut, however, much data was accumulated, and was hailed in reports as helping space research. Levin was introduced to the Queen in 1963 when she met the expedition members.

Yet while this last quasi-imperial adventure was making headlines, the modest but cosmopolitan Levin, a talented painter and draughtsman who had qualified in the 1930s at the Sorbonne and the Ecole Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, was exploring elements of European architectural progress that would stand Britain in better stead. His chosen medium was wood, his speciality architectural theory. For his own pleasure he had learned from Hungarian tutors in Paris how to make furniture.

He now had the job he wanted, as Chief Architect of a small but influential research body, the Timber Development Association, based in High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, and in the 1950s and '60s travelled widely to seek out the best new techniques. One in which he took a particular interest was the use of "glulam" – glued laminated wood, patented by Otto Hetzer in Weimar in 1905 – to produce elements such as beams and trusses for roofs and other large structures. These skills, he found, were now flourishing in the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland and Scandinavia after being lost to Germany when the slump of the 1920s had forced Hetzer's factory to close.

Back in Britain Levin recommended that "attention should be given to some of the practices successfully employed on the Continent," and appeared in a television discussion programme, Wood: the First Plastic, in February 1970 on BBC2, describing ideas for multi-storey buildings and shell roofs.

His own fascination with using wood on a grand scale had begun in the mid-1950s with a commission to design an examination hall for the University of Khartoum in Sudan, for which he chose to use the plentiful hardwoods of the surrounding region. Levin, who was born in Haifa, then in Palestine, had come to London in the late 1930s straight after qualifying to work as an architect's assistant, and was employed in a succession of firms through the war, when he also helped with fire rescue services and, whenever he could, drew pictures of bombed buildings. He was soon promoted and after running various offices was invited to Haifa, in Palestine (now Israel), to be City Architect and Town Engineer.

His association with Britain, however was strong. He had spent a few years of his childhood in Liverpool, after his father Moshe, a British citizen, was threatened with arrest by the Turks at the outbreak of the First World War, and had fled Haifa with his wife and seven children, going first to Alexandria, then Port Said, then Britain. Eventually the family returned to Haifa, where Levin had his secondary education at the Re'ali School. He married a childhood friend, Raya, whom he had met again while studying in Paris.

The couple had two sons, Daniel and Theodore, and, apart from the spell in Haifa, were to live for 40 years in St John's Wood in London until Raya's death in 1993. Levin then moved to Willesden, and is survived by his sons and by his younger sister Malka.

For Levin, a quite different landmark building from the little Silver Hut was to be a quiet source of pride. In one of the London architects' offices in which he had been a young assistant, he had once, before moving to new employment, drawn a rough plan for a cinema. That drawing became, he was always convinced, the celebrated black Art Deco Odeon Leicester Square. "I designed a cinema and later I was amazed to see it built, in Leicester Square," he said. "I did not prepare any working drawings, but I saw that they built it."

Ezra Levin, architect: born, Haifa, Palestine 26 November 1910; married 1932 Raya (died 1993; two sons); died London 4 June 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies