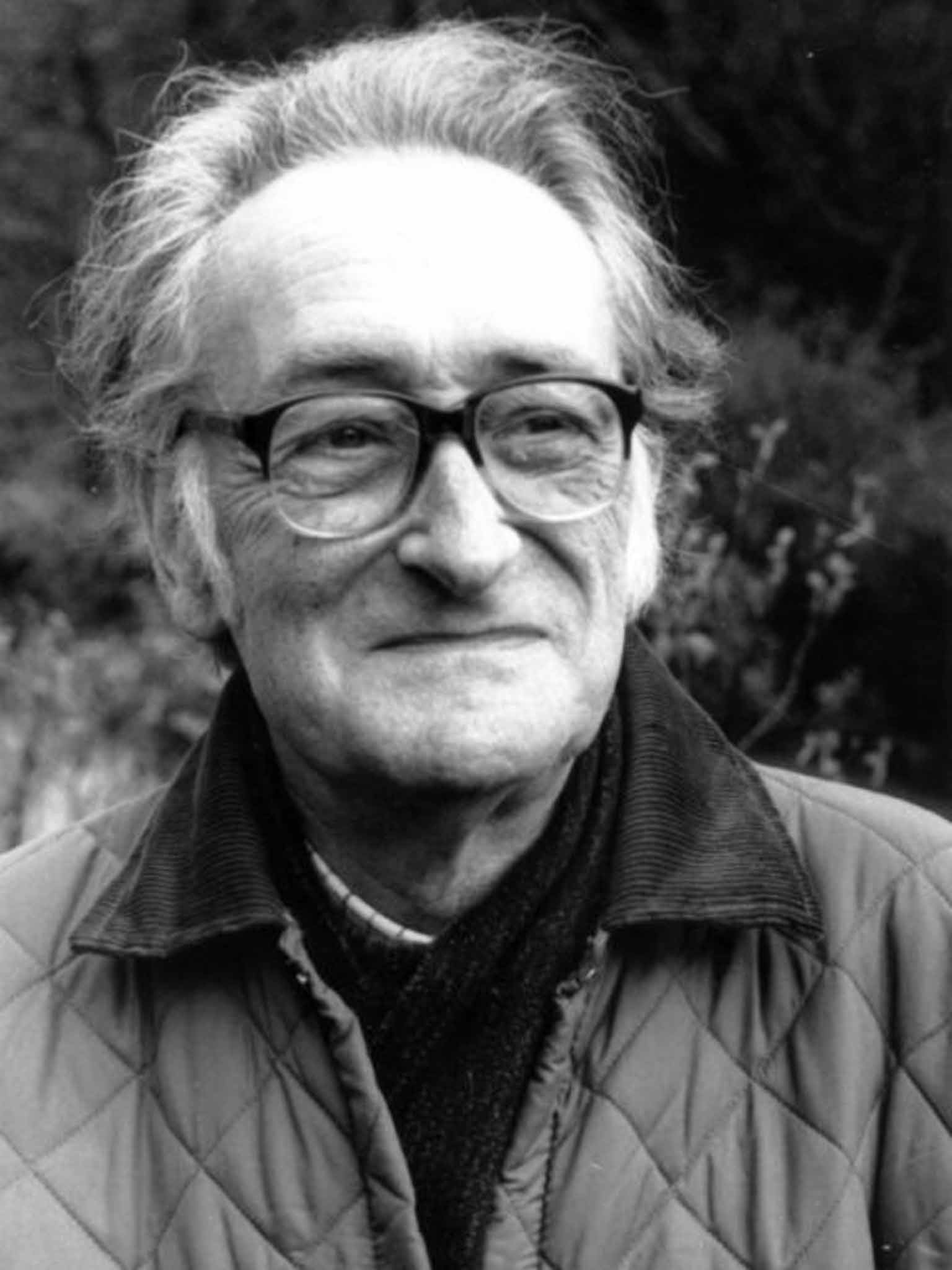

Charles Tomlinson: Poet and translator whose writing was influenced and nurtured by work from the US and around the world

At its best, Tomlinson's is a meditative kind of verse which keeps a close eye on particulars, whether man-made or natural

As well as his many collections of poems, Charles Tomlinson, that most internationally inclined of English versifiers, published literary criticism and translations from the works of other poets and edited the Oxford Book of Verse in English Translation (1980). His own poetry, from first to last, was influenced and nurtured by poetry from other languages, and especially by poetry from Italy.

Born in Stoke-on-Trent in 1927, he studied at Queens' College, Cambridge (the poet and critic Donald Davie, up from Barnsley, was his exact contemporary) and then went on to teach at Bristol University until his retirement.

His schooling in the 1940s had thrown him into the company of various German refugees, teachers at his local high school, who introduced him to Buchner, Rilke, Nietzsche and others. He even read the plays of Maeterlink. Who would have guessed that such enlightened internationalism would be thriving amid the smoke stacks of Stoke in those days?

At 15, he bought an edition of The Selected Poems of Ezra Pound in a favourite local bookshop. This encounter with the most controversial American poet of the 20th century helped to shape his life and his work as a poet; Tomlinson marvelled at how Pound could make verse sing with such casually demotic rhythms. For many years Tomlinson was generally regarded as the man who helped to familiarise English readers with the work of various leading poets from that country, all hitherto neglected – William Carlos Williams, Louis Zukofsky, Marianne Moore, George Oppen and others – all of whom became friends or close acquaintances.

Tomlinson found in these poets a clarity of address – he remarked that Oppen's work reminded him of good, honest carpentry – that seemed to be absent from so much of the poetry in 1940s England, with its overblown rhetoric and shrill metaphysical vagaries. He was in flight from the influence of Dylan Thomas and others of that bibulous, religiose ilk. He was looking for honest, plainsman's work, a species of writing which might after all be able to claim some kinship with good prose. And these Americans seemed to offer him exactly that.

His first book of poetry from a major press, Seeing is Believing (1963), was so shaped by those influences that it was accepted for publication in the US two years before it appeared in England under the imprint of Oxford University Press, his publisher until the closure of its poetry list in 1999. (Carcanet Press published the books of his last decade and a half, including a New Collected Poems in 2006.)

Tomlinson has been called a Modernist, but his poetry more truly belonged to traditions more native to England, even if his first published work seems to resist such a judgement. These early poems can be found in The Necklace (Fantasy Press, 1955, a publisher which also did a hot line in eroticism). These first attempts, much too dry and serious and old before their time, often read like carefully re-written versions of poems by Wallace Stevens.

Tomlinson's friend Donald Davie, as fellow poets are wont to do, praised the poems to the skies when the book was re-published by the OUP in 1966: "Once we have read them,' he wrote in an expansive introduction five pages in length (the text itself was 16 pages long), '[the world] appears to us renovated and refreshed, its colours more delicate and clear, its masses more momentous, its sounds and odours sharper, more distinct." As sincere whole-hearted and well-meaning a gobbet of back-scratching as could ever be wished for.

At its best, Tomlinson's is a meditative kind of verse, even Wordsworthian at times, which keeps a close eye on particulars, whether man-made or natural, and which often builds through long and intricately modulated sentences. He wrote, often, descriptive verse about his travels, but, from first to last he would also intermittently return in his mind to his native Midlands and offer autobiographical glimpses of his early life in industrialised Stoke, with its terraced streets and looming pottery kilns.

He did so most extensively in a 1974 collection , The Way In, which includes a poem called "At Stoke", his most bald statement of feeling about the place of his birth. It was a place of ash tips and "sullen in-betweens", desolate and diminished, full of "discouraged greennesses". The photograph by Ken Lambert on the cover of its first edition tells us almost as much as we need to know about the context from which this fine scholar/poet had emerged: a child scrapes snow off a wet pavement in front of a characteristically bleak row of terraced housing built for the Victorian working man.

Yet Tomlinson would never tolerate his upbringing being described as working-class. He thought that too pigeon-holing, too tainted by ideology. The phrase "working people" pleased him well enough, though. His childhood appears again, with great vividness, in Cracks in the Universe (2006), his last full collection. In a cycle of six poems entitled "Lessons", we glimpse intimate moments from his schooldays – of the morning when he played the part of Tasmania in the Empire Day Pageant. He climbed up on to the stage robed and shoeless: "a splinter from the floor/penetrated my naked foot as keen/as a Tasmanian arrow."

Tomlinson was from first to last a serious- minded poet, and it is not often that you find him relaxing into humour in verse. The task in hand is altogether too serious a matter to countenance irony or levity of any kind. There is, however, a great deal of not-so-sly humorous observation in a 2001 book of prose, American Essays: Making it New. Here he anatomises individual poems, and writes of the personal quirks of some of those great American poets he had come to know and learn from. Here is an observation of Ezra Pound in old age in Siena. Pound was celebrated for his taciturnity in his final decade, and had many bad decisions worth brooding over. "He sat, concentratedly engaged in removing every particle of ice cream from the bottom of his dish with a plastic spoon."

He received many awards, including the 1993 Bennett Award and, in 2004, the Premio Internazionale di Poesia Attilio Bertolucci. He deserved that nod of thanks from the Italian prize committee; a bilingual edition of Tomlinson's translations from the work of Bertolucci was published in 1993.

Alfred Charles Tomlinson, poet and translator: born Stoke-on-Trent 8 January 1927; CBE 2001; married 1948 Brenda Raybould (two daughters); died 22 August 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies