Dorothy Tyler: High jumper who met Hitler then became the first British woman to win an individual Olympic medal in athletics

"They're all cheats!" The little white-haired woman seemed almost angry as she made this announcement to a 500-strong audience that included a couple of peers of the realm and the Princess Royal. Dorothy Tyler certainly got people's attention. It was a 60th anniversary event of the second London Olympics, where in 1948 Tyler won her second Olympic silver medal. She was the first British woman athlete to win an individual Olympic medal, and she twice might have been the first to win gold.

It was in 2008 that Tyler was a guest of honour at an awards lunch, with John Inverdale taking his microphone around the tables. Dick Fosbury, the man who in 1968 had re-invented modern high jumping, was over from America and provided a typically gracious anecdote.

But when Inverdale turned to Tyler, the audience sat up from their digestifs and coffee. Tyler wrote off 40 years of sporting history, declaring that the Fosbury Flop should never have been allowed. "You can't go over the bar head first," said Tyler. "It's cheating." Back in the spotlight for the first time in decades, Tyler, a pioneer of women's sport, stole the show in a typically combative style which left her uncowed by Adolf Hitler when she met him as a teenager.

She was born in Stockwell, south London, in 1920. When she won a schools sports day, her prize was membership of the local athletics club. At that time, sporting participation by women and girls was frowned upon. "They didn't like us to do the long jump back then," she said, "because they thought it would damage our abdominal muscles." Odam said she used her sport "as means of escape from home".

In 1935, Odam finished second in the high jump at the national indoor championships at Wembley, and a year later the teenager was one of 12 women in the British athletics team for the Olympic Games in Berlin. "When we got there, there were 40-foot Nazi flags everywhere, everyone seemed to be in uniform," she recalled. "It was all very militaristic. We were staying in a large dormitory. The first morning, I was woken up by the sound of marching, and outside there were hundreds of Hitler Youth parading."

In Berlin for a fortnight before her event, "the only time the chaperones allowed us out, they took us shopping. When the shop assistant said 'Heil Hitler!', we just said back: 'Hail King George'." Invited to a reception organised for the women competitors by Joszef Goebbels before the Games, it was there the London schoolgirl met Hitler. Asked what she made of the Führer, Tyler said, "He was just a little man in a big uniform." She said "someone suggested I should have given him a slap. But I think that would have just got me into trouble".

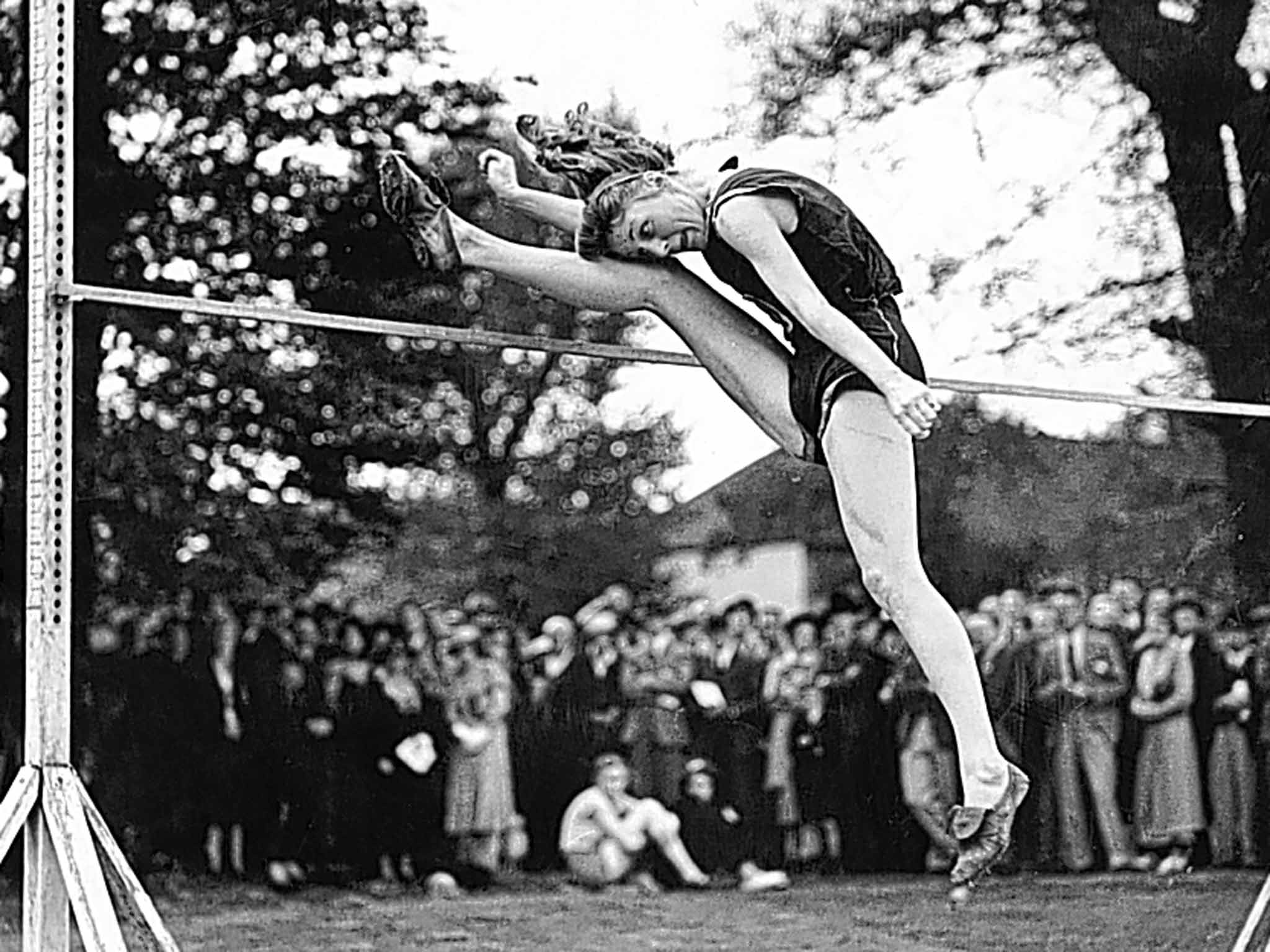

Women had first competed at the Olympics eight years earlier, and in 1936 were allowed to compete in only five events. Odam wore home-made vest and shorts. "I didn't even measure my run-up. I just picked a spot, ran and jumped over the bar. It was just something I did."

In only her second international competition, abroad for the first time, in front of 80,000 people in the Olympic Stadium, Odam – using the scissors technique which allowed jumpers to land on their feet in the shallow sand pits of the era – she was the first to clear 1.60 metres. No one would jump higher in the three-hour competition staged on a fiercely hot day.

Under modern countback rules Odam would have won. But under the 1936 rulebook a jump-off was called for, and as the young Briton wilted in the heat Ibolya Csak of Hungary took the gold. Odam, according to the official British Olympic Association report, "certainly excelled herself and with a little luck might have been our first woman champion".

Two years later Odam had to give up her office job to take four months out to travel to Sydney for the third Empire Games, where she was the only Englishwoman to win athletics gold, setting a Games-record 5ft 3in – the same 1.60m height she had managed in Berlin.

In 1939 she broke the world record with 1.66m, only to have it snatched away from her soon after by a jump by Germany's Dora Ratjen. Tyler had been suspicious of Ratjen since they'd met in Berlin. Tyler recalled, "They wrote to me telling me I didn't hold the record, so I wrote to them saying, 'She's not a woman, she's a man'. They did some research and found 'her' serving as a waiter called Hermann Ratjen. So I got my world record back." Tyler's world record was formally recognised by the sport's world governing body, the IAAF, in 1957.

During the Second World War Tyler's home was bombed and she joined up as an RAF auxiliary lorry driver, also working as a PE instructor at 617 Squadron – the Dambusters. Afterwards she took a secretarial course, "because secretaries don't work on Saturdays", enabling her to prolong her track career. She competed in four Olympic Games and won two Empire Games gold medals before her retirement in 1957.

In 1940, Odam married Dick Tyler, though she would barely see him for five years while he was on active service. After the war, they had two sons, with Barry, the younger, born nine months before the 1948 London Games. His mother had barely got back into competition in time to gain selection.

In the Olympic final, again on the last day of the Games, Tyler and Alice Coachman both cleared the Olympic record-height 1.68m, but the American did it on her first attempt. Now the countback rule worked against Tyler. Still, her second Olympic silver made her the only woman to win medals either side of the Second World War. She would also establish a record of competing for Britain at four Olympics.

After retiring, Tyler taught PE and was an innovative coach, calling on Margot Fonteyn to work with some of the country's leading athletes. She took up golf at 47, becoming an 11-handicapper, and was three times national over-80s champion; a stroke in 2006 curtailed her playing to three times a week. Increasingly frail, she made her last public appearance as official starter for the 2012 London Marathon.

She died at a nursing home in Suffolk following a short illness. She is survived by Dick, 97, her husband of 74 years, their sons and four grandchildren.

Dorothy Jennifer Beatrice Odam, athlete and coach: born London 14 March 1920; MBE; married Dick Tyler (two sons); died Suffolk 25 September 2014.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies