Mysterious to the end, JG Ballard's daughters reveal his secret archive

Author had always denied keeping notes and manuscripts

Support truly

independent journalism

Our mission is to deliver unbiased, fact-based reporting that holds power to account and exposes the truth.

Whether $5 or $50, every contribution counts.

Support us to deliver journalism without an agenda.

Louise Thomas

Editor

When JG Ballard was pressed in 1982 on whether he would donate his manuscripts, letters and notebooks to a national collection for posterity his answer was clear. "There are no Ballard archives," he said.

Yesterday, a little over a year after the author's death from prostate cancer, the British Library revealed a treasure-trove of an archive that had been carefully – and secretly – preserved by Ballard.

The collection of manuscripts, notes, rough drafts – often repeatedly amended – as well as school reports, and material from the Shanghai camp in which he was interned by the Japanese with his parents during the Second World War – may come as as shock to scholars who had taken him at his word, and will doubtless shed new light on one of the most visionary British writers of the 20th century.

In its present state – as it sits uncatalogued in 15 bulky boxes of manuscripts, notebooks filled with hastily jotted ideas for future novels, science fiction magazines in which his first short stories were printed, including one in which the germ of the idea for his novel, Empire of the Sun, appeared – its secrets have yet to be revealed.

The archive, given as a gift by Ballard's daughters, Fay and Bea, in lieu of £350,000 inheritance tax, has already provided a glimpse into the creative processes of the author, whose manuscripts show how fervently he re-drafted, time and time again, until he was happy with the final outcome.

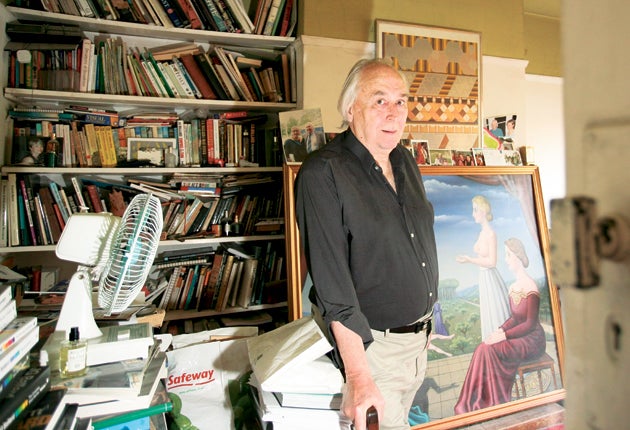

Ballard told his daughters where they could find his manuscripts at his home in Shepperton, Middlesex, before he died last April. Intensely modest by nature, Fay recalled that he was surprised by the idea that the British Library may want his archive. "He was very modest. We had several conversations about the material and he said, 'do you think they would be interested, darling?'" she said.

Jamie Andrews, head of modern literary manuscripts at the British Library, said there was an extraordinary wealth of material in Ballard's collection including, most amusingly, a school report from when he was a 16-year-old student which noted the usual complaint that "he could do better" but also acknowledged his rich imagination and the fact that he was at the top of the class in English. There were also notebooks in which he jotted down thoughts and ideas.

One of the most remarkable things about the manuscripts for his novels, added Mr Andrews, was the level of revision to his writing.

"There was very full evidence that he did a lot of reworking and Tippexing. The first draft was predominantly handwritten and then he would type up these pages, which have been thoroughly revised. Some of these individual pages are works of art in themselves; you see a determination and a violence in the way things have been accrued.... The cutting down and corrections, it was furious. Everything had to be hacked off, everything had to be worked out," he said.

Ballard lost his wife in 1964 after she caught pneumonia on a family holiday in Spain and died within a few days. At the time, he was a writer in his 30s, alone with three small children – Jim, nine, Fay, seven, and Bea, five. But he took single parenthood in his stride while continuing with his writing, and his children remember him as a kind and dedicated father.

His children played in the nursery while he wrote in his study, but he still found time to iron their school uniforms and cook meals.

"We had a pact and would leave him alone for a few hours, but we could not resist slipping through his door to ask questions. He would be in the middle of composing a sentence, mouthing out the words as he wrote," said Bea Ballard.

Ballard had lived through a great deal in his life; he had been interned by the Japanese in a prisoner-of-war camp between the ages of 12 and 14, an experience that inspired Empire of the Sun, decades later. For two decades after his internment, he sought to forget the traumatic experience but then found himself drawn back. He began writing to others connected to the camp, asking for items that could help with background research for Empire of the Sun.

He had kept some material from his boyhood, including a detailed map of the camp, and as an adult, he amassed minutes from the meetings that took place there, a register of those who had been interned there, which included the names of his parents, and a graph which illustrated the paltry intake of calories that prisoners were given each day.

An extraordinary life

Ballard's 1947 spring term school report

After the turmoil and danger of wartime in Shanghai, Ballard returned to England to complete his education at The Leys School in Cambridge. The 16-year-old Ballard's prowess in English was spotted by his fifth-form teacher who wrote: "He has remarkable ability and general knowledge." However, the teacher added: "With greater concentration, his work could be even better."

Lunghua internment camp blueprint, September 1943

From 1943, Ballard and his family were interned in Lunghua camp, outside Shanghai. Later in his life, he was sent original documentation relating to life in the camp that had been collected and saved by the wife of the English chairman of the internees' committee. This plan of the camp shows Block G where the Ballard family were allocated one small room.

Heavily revised typescript of 'Crash'

The dark tone of the 1973 novel appears to be matched by the heavy, almost violent layers of corrections and revisions evident in this draft of the controversial novel, writes Jamie Andrews, from The British Library. Ballard would habitually begin a complete draft by hand, before moving to a second, typewritten version which would be further revised by hand.

Handwritten manuscript of 'Empire of the Sun'

Published in 1984, the novel, while fiction, contains clear autobiographical allusions to Ballard's experiences and reflections in the internment camp during the Japanese occupation. The work was taken to a new audience when Steven Spielberg adapted the novel for film three years later. This first draft runs to over 800 handwritten pages, and contains numerous revisions.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments