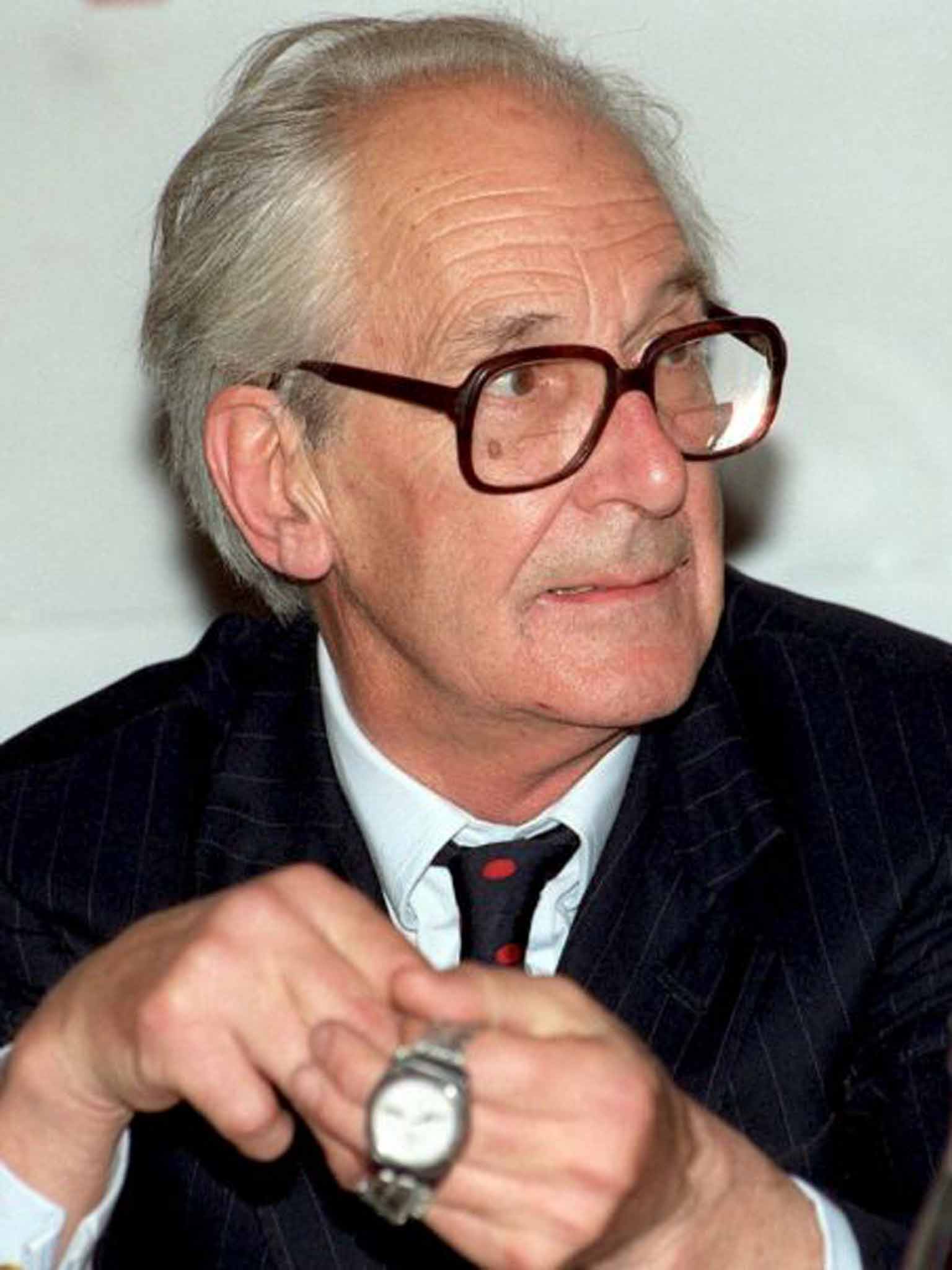

Professor Sir Raymond Carr: Celebrated scholar whose work explained and illuminated Spanish society before, during and after the Franco regime

In British academic circles he was known as an amiable, self-deprecating, brilliant professor, shrouded in cigarette smoke, a keen musician with a spectacular social life - in Spain he had almost the status of a national hero

Thirty years ago, working on an "O" level history project on 20th century Spain, I borrowed (and to my shame, never returned) several books from a library. One of them – on its cover a famous pro-Republican poster depicting a priest, two soldiers and an industrialist, complete with Nazi Party badge, key elements of Spain's reactionary forces in its Civil War – turned out to be Modern Spain, 1875-1980, by Sir Raymond Carr.

As I have increasingly appreciated ever since, it would be hard for historical investigations into Spain's recent past, even the flimsiest of teenage efforts like mine, not to have Carr's work as some kind of point of reference. That was – and to some extent still is – also true inside Spain, where, at the height of Franco's dictatorship, Carr, based in Oxford, laid down some crucial foundations for the country's own academic understanding of its 19th and 20th century history.

Carr's work from the 1960s onwards filled a significant, ground-breaking gap in Spanish historiography. Franco's censorship system rendered a politically sensitive subject like modern history (almost inevitably including analysis of the Franco regime itself) a minefield for Spanish academics, particularly if they were rash enough to write for audiences other than a handful of their colleagues. Carr was hampered by no such restrictions when it came to writing about Spain's tumultuous recent past. His writing was different to work by earlier great British Hispanists like Gerald Brenan. Brenan's books like South from Granada provided unforgettable, but somewhat romanticised, insights into 20th century Spain.

But whereas Brenan cheerfully admitted that he had made up one of his footnotes in one of his historical works, Carr stuck to explaining and analysing tangible and reliable political and sociological data in a hugely readable fashion. For example, discussing comparative levels of wealth in Madrid and poverty-stricken Cuenca, Carr compared percentages of television ownership. Such examples helped portray Spain as a "normal" European nation, as Carr strongly believed it was, rather than resort to the clichéd imagery abroad of Spain as a land overrun with bullfighters and flamenco dancers.

He was born in Bath in 1919 into a religious working class family – he was, he wrote, "the son of a primitive Methodist mother and a puritanical father"; a series of scholarships culminated in a First in History from Oxford in 1941. He switched from studying Swedish history to Spain partly because he was struck by what he saw of the country on his honeymoon in Torremolinos. (It was also partly because, as he once put it, "studying the price of copper in 16th century Sweden was rather tedious.")

Scandinavia's loss was Iberia's gain, as his first book on the subject, Spain 1808-1939, immediately proved. Published in 1966, the book melded extensive archival research and, indirectly, Carr's increasingly direct knowledge of an ample cross-sector of Spanish society, including leading military figures from both sides of the 1936-1939 Civil War.

Notably objective about such conflicts, he outlined in a thorough, clear fashion the origins and changes in the fault lines of the country's tragically self-destructive internal political and social divisions. As a result Spain 1808-1939 stands out, then as now, as a key text in the modern historical study of Spain. It also saw Carr unintentionally acquire the mantle of father figure to British and American Hispanists (a term, he disliked) for decades to come.

Other outstanding works were to follow, among them The Spanish Tragedy: The Civil War in Perspective (1977); Spain: From Dictatorship to Democracy (1981) co-written with Juan Pablo Fusi; and Modern Spain (1981). One appealing aspect they shared was Carr's use of sharply amusing anecdotes to illustrate his points. Describing an occasion on which the early 20th century populist demagogue Alejandro Lerroux was caught drinking champagne, Carr relayed his apparent boast that he was only drinking today what the workers would drink tomorrow. Carr's deep knowledge of and enthusiasm for Spanish literature – such as one of the best novelists of the Franco era, Miguel Delibes – was also an indelible influence.

Although he kept his distance from Franco's regime, Carr was subsequently on good terms with King Juan Carlos as well as numerous politicians in Spain's fledgling democracy. His work gained much recognition at state level; in 1999 he received the Prince of Asturias prize, the country's most prestigious public award, for Social Sciences "for bringing a global vision to contemporary history, which… has contributed to a better understanding of the Civil War and the transition to democracy. [His work] has become a role model for other research."

Carr was eclectic: he wrote two works on foxhunting, of which he was an enthusiast, in 1976 and 1982, as well as books on Sweden and Puerto Rico. His lifelong academic attachment to Oxford, first as a Christ Church student, then with a fellowship at All Souls and New College, allowed him to pursue his own research into Spain and oversee, and inspire, that of countless British and Spanish students.

For nearly 20 years he was Warden of St Antony's College, Oxford, which specialises in modern international studies. A Fellow of the British Academy since 1978, he was knighted on retiring in 1987, when his colleagues gave him a horse as a farewell present. He continued producing pithy book reviews until his early 90s for such publications as The Spectator.

In British academic circles he was known as an amiable, self-deprecating, brilliant professor, shrouded in cigarette smoke, a keen musician, with a relentlessly spectacular social life. But in Spain he had almost the status of a national hero. As the conservative daily ABC said in its obituary, "He is a basic reference point for the knowledge of our own history… the incarnation of a synthesis of a passionately held relationship between a Briton and Spain, both on a scientific level and an emotional one."

Albert Raymond Maillard Carr, historian: born Bath 11 April 1919; Kt 1987; married 1950 Sara Ann Strickland (died 2004; one daughter, two sons, and one son deceased); died 19 April 2015.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies