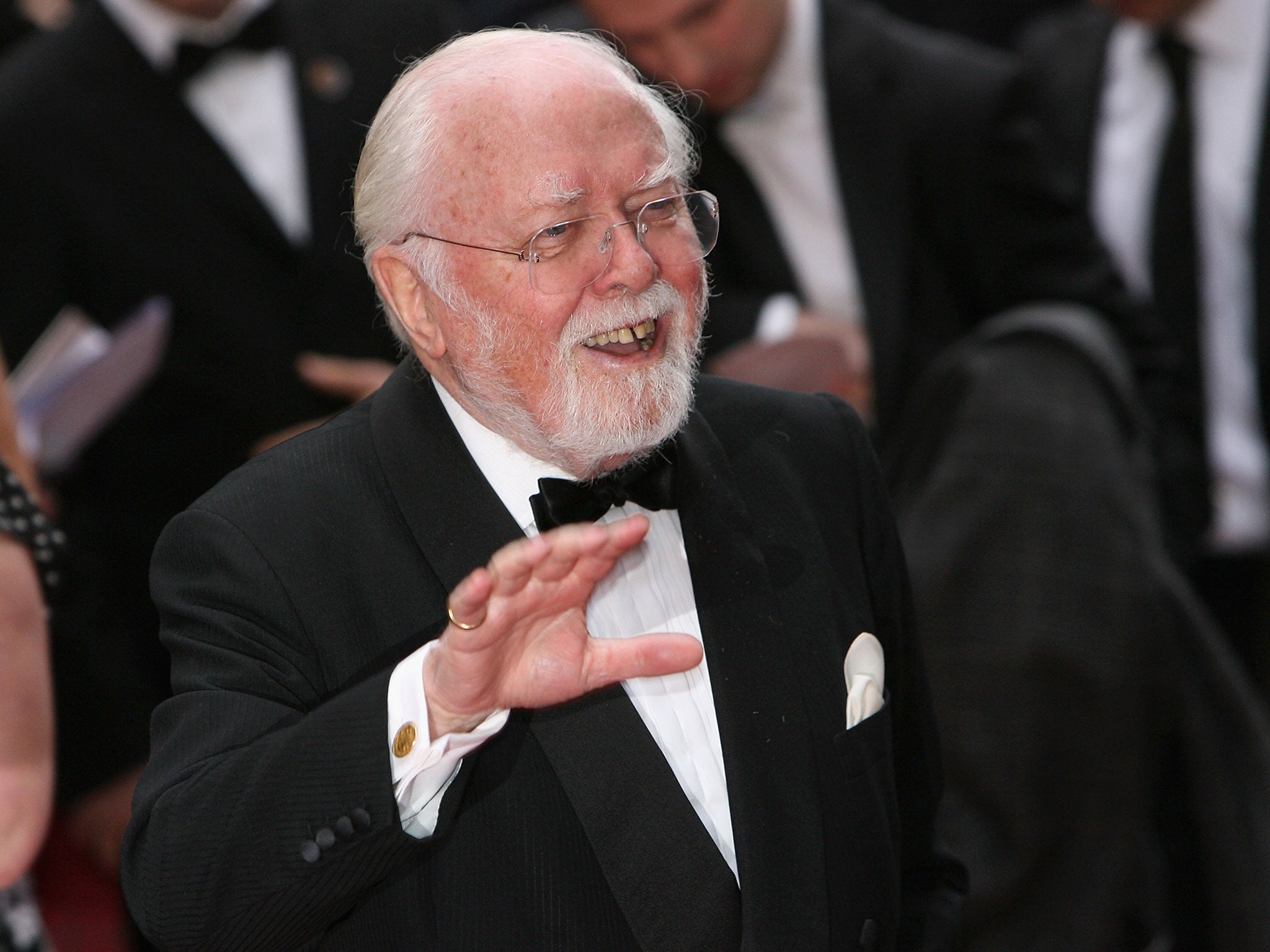

Richard Attenborough appreciation: A figurehead for the British film industry and its de facto leader

His work always boasted extraordinary craftsmanship and attention to performance, writes The Independent's lead film critic Geoffrey Macnab

Richard Attenborough’s status as one of the most influential and inspirational figures in late 20th Century British film history can’t be questioned.

Attenborough, who has died aged 90, was a relentless lobbyist on behalf of British cinema. Alongside his own, often epic films (Gandhi, A Bridge Too Far etc) and his prodigious work for charity, he emerged in the latter part of his career as the British film industry’s greatest and most effective cheerleader.

We have Attenborough to thank for persuading the then Prime Minister John Major in the early 1990s to allow National Lottery funds to be used to back British film production. Just as the Lotto cash did so much to help British athletes win Olympic medals, it thoroughly invigorated British filmmaking.

Oscar winners like The King’s Speech, Palme D’Or winners like Ken Loach’s The Wind That Shakes The Barley and Venice Golden Lion winners like Peter Mullan’s The Magdalena Sisters were all Lottery backed. In a distant way, Attenborough made them possible. He was a figurehead for the British film industry and its de facto leader; a life-long Labour supporter ready to lobby even a political opponent like Margaret Thatcher if that was what it took. He was one of the galvanizing figures behind British Film Year in 1985, a PR exercise that gave British cinema a much needed boost when it was at its absolute nadir.

In Pictures: Richard Attenborough 1923 - 2014

Show all 24Critical opinion is split on Attenborough’s work as a director. He won Oscars for Gandhi and had an obvious flair for mounting huge widescreen epics, full of crowd scenes and spectacular set pieces, and yet his finest film was arguably one of his smallest and most intimate. Shadowlands (1993), based on the love affair between C.S.Lewis and American writer Joy Davidman, was a sensitively helmed tearjerker quite beautifully played by Anthony Hopkins and Debra Winger. He felt that his own greatest skill was directing actors.

“You have one operation, which is commanding a regiment, commanding an army. You either enjoy it or you don’t. I do. I love organising and making all the logistics work,” he reflected on the funeral scene in Gandhi which he shot with 19 cameras. At the same time, he also acknowledged that “the scenes played by one or two people who have lines are just as important, even set against that huge panorama.”

Attenborough accepted that his films, ranging from biopics of his beloved Chaplin and the young Winston Churchill to musicals (A Chorus Line) and political dramas (Cry Freedom) “aren’t the work of one artist whose work is there on screen for everyone to see.” If he wasn’t an “auteur,” his work always boasted extraordinary craftsmanship and attention to performance.

When I interviewed Attenborough for Sight and Sound magazine on his 80th birthday in 2003, I remember being surprised by the gleaming Rolls Royce parked in the garage of his Richmond home. Back then, Attenborough had such a sainted reputation you half expected him to turn up at his front door dressed in robes like Gandhi. You didn’t imagine he would be interested in such trappings as luxury cars. If he was more worldly than his public image sometimes suggested, and also far more outspoken, the British director, actor and producer was also kindly and wildly enthusiastic, “an idiotic optimist” as he called himself.

The effusive, patrician figure of the 1980s and 1990s, who called everybody “darling,” patted you on the knee and made phenomenal amounts of money for charity, presents a very stark contrast to the Attenborough we first saw on screen in the early 1940s. As a young actor, Attenborough excelled at playing neurotics and delinquents. He was very striking in a small role as the terrified young sailor in In Which We Serve (1942). While Noel Coward was a model of British pluck and phlegm commanding the ship above deck, Attenborough was in a nervous frenzy below. He is so young and forlorn-looking that he has a Bambi-like quality as he is dressed down by his captain.

In the Boulting brothers’ Graham Greene adaptation Brighton Rock (1947), Attenborough was the razor wielding juvenile spiv, Pinkie. Again, it is his boyish quality that registers. Even as Attenborough’s commits sadistic acts of savagery, he seems strangely vulnerable himself: an adolescent trying to prove his machismo in an adult world. His cruelty to Rose (Carol Marsh), the waitress who falls in love with him, is motivated by self-recognition. He can’t bring himself to accept that he is young and innocent too.

Attenborough’s parents were politically and socially active. Frederick, a Cambridge don who became principal of Leicester University, and Mary, a founder of The Marriage Guidance Council, were supporters of the Republican cause during the Spanish Civil War. They adopted two refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany on the Kindertransport.

“It was an extraordinary background my brother Dave and I had,” Attenborough later recalled. “My parents believed in the responsibility of one human being for another and in the idea that you had little right to experience the phenomenal joys of life unless you were aware of others who could be three feet or 3,000 miles away, facing difficulties you had no understanding of. They believed in the principle of putting something back. That, for them, was what life was about. And boy, they lived their life to the full.”

His parents frowned initially on his choice of acting as a career but became more supportive once he won a scholarship to RADA.

As an actor, Attenborough had been heavily influenced by Edward G. Robinson, whom he met during the Second World War. They both appeared in the Boulting brothers’ wartime Air Force propaganda film, Journey Together (1945.) Robinson taught him that “you have to sort out the character long before you come on set.” Attenborough (also an admirer of Steve McQueen, with whom he worked on The Sand Pebbles) therefore took something akin to a Method approach to his roles. When he played serial killer John Christie (a role he took partly because of his opposition to capital punishment) in 10 Rillington Place (1971), he did a huge amount of research, meeting police officers who had worked on the case and interviewing acquaintances of the killer. His performance as the balding, bespectacled killer was chilling precisely because he tried so hard to “find the nuances in the character” rather than portray him simply as a monster.

As a director, Attenborough invariably tackled themes that reflected his parents’ preoccupations. “I want cinema to contribute something to argument, to thought, to antagonism, to anger, whatever, but always related to human affairs and human decency... I would be very sad if cinema were to deteriorate to such an extent that such films were not viable,” he stated.

In his acting career, Attenborough was sometimes less discriminating. He seemed very natural casting as Santa Claus in Miracle On 34th Street and was in feisty but avuncular form as the creator of Jurassic Park.

It was his misfortune to be a screen actor in the 1950s, when British films were in a rut. “I was bored stiff with much of the acting I was doing. I made some dreadful films. Most of the films were to pay the gas bill,” he said of the roles he took in this period.

“I think you’ll have quite a nice little run,” Agatha Christie told him when he and wife Sheila Sim began their two year stint on the original production of The Mouse Trap. It was success of a kind but not what Attenborough wanted.

In the late 1950s, Attenborough and his close friend Bryan Forbes reacted to their frustratioins by setting up their own production company Beaver Films, which made such stirring work as The Angry Silence,Whistle Down The Wind and Seance On A Wet Afternoon. Attenborough was the producer, sometimes the actor, but said he had no great desire to direct - until, in the early 60s, he was approached by Mothilal Kothari, a civil servant working with the Indian high commission, who suggested a film about Gandhi. After a 20 year battle, he finally made it.

One of Attenborough’s final dream projects was to direct a biopic about the English Eighteenth revolutionary and author of The Rights Of Man, Tom Paine. As the choice of subject matter suggested, he still regarded himself as a radical. To the British public, he may have appeared an establishment figure but that was not at all how he saw it. In his films as in his public life, he was a relentless campaigner with an old fashioned belief that cinema could inspire and enlighten audiences as well as entertain them.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies