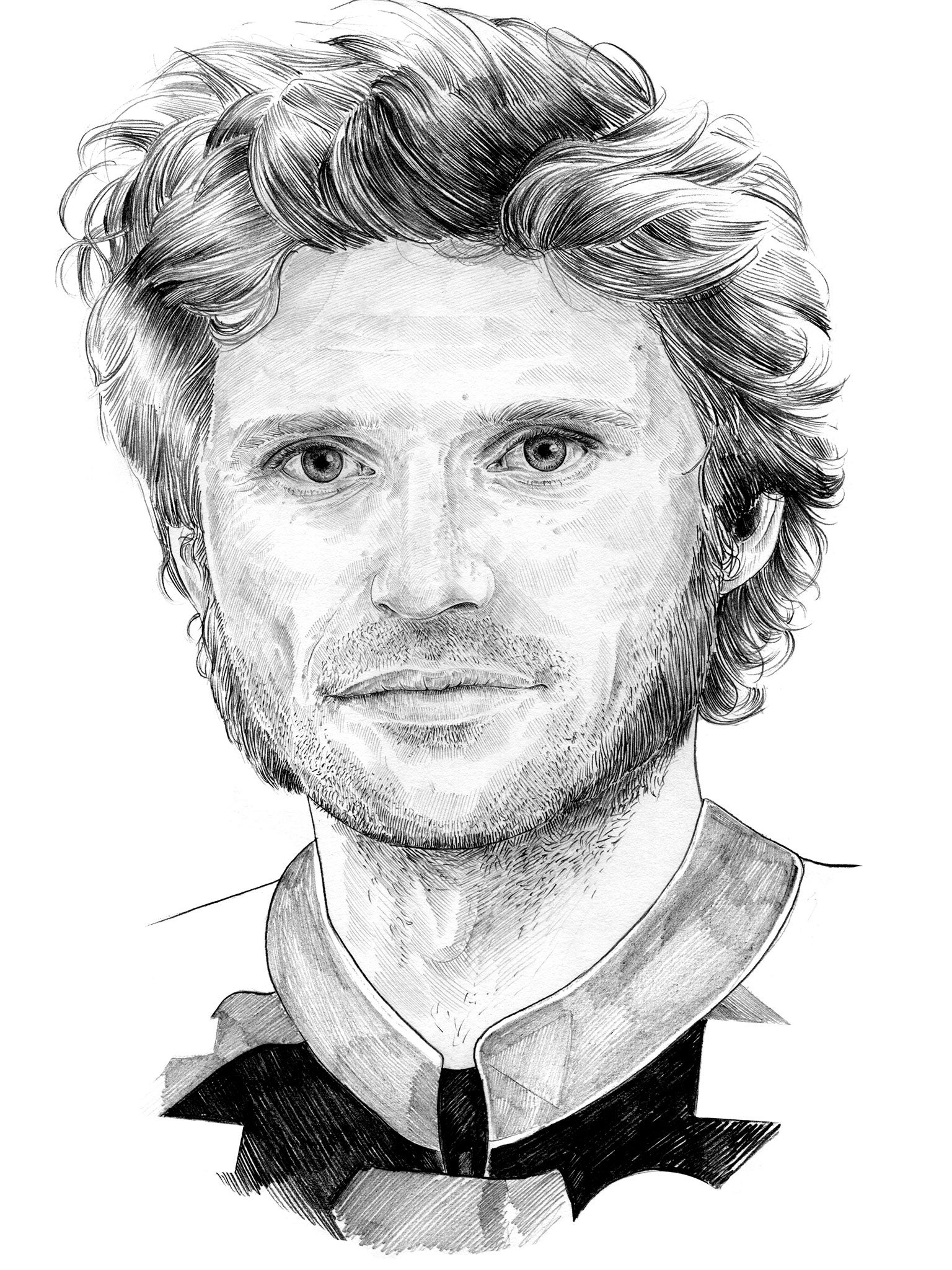

Guy Martin profile: Jeremy Clarkson’s perfect replacement on Top Gear

The motorbike racer mooted as Top Gear’s next host combines a dislike for celebrity with gentle blokiness

Before he and his sideburns were famous – before all the primetime TV series and the best-selling autobiography – Guy Martin popped up in a short film about the 2009 Isle of Man TT race.

“It was just one of the standard features you do about the runners and riders,” says James Woodroffe, whose film for ITV4 was intended for fans of the race. “But rather than talk about machines and what he liked about the course, like most of them, Guy started talking about the molecular structure of tea.”

The clip survives on YouTube. After a tour of his shed near Grimsby, Martin contemplates a mug, one of the 15 or more he empties each day. “Nine times out of 10, people put the milk in last,” he says in his now familiar, scattergun speech. “But if you put the milk in first, the overall result is an emulsion, which is a far better result than a mixture... it’s all about the molecular reaction between the hot water and the milk.” He adds: “I’m a bit sad, I take things like that into account.”

Dual addictions – to death-defying speed and tea – mixed, in the right way, with an infectious curiosity about how stuff works have since turned a lorry mechanic and bike racer with Asperger’s syndrome into one of Britain’s unlikeliest, and most reluctant, celebrities. Now, six years after Woodroffe’s boss at North One Television showed that clip to a suit at the BBC (“he said, ‘brilliant, now what does this man like?’,” Woodroffe remembers) Martin is being tipped for one of the biggest jobs on the box.

According to unverified reports, the 33-year-old has been in talks about presenting Top Gear, alongside the former model Jodie Kidd and the actor Philip Glenister, both of whom have dabbled in motoring TV. The trio has been billed as a “dream team” to rebuild the global brand that crashed and burned after Jeremy Clarkson’s steak-inspired fracas. It is hard to imagine Martin’s catering demands extending far beyond cups of builders. Yet while the rumours are testament to his natural talent, leading-man jawline and thoughtful, gentle blokiness, nothing about Martin suggests he would go anywhere near Top Gear. Asked in an interview earlier this year whether he wou ld consider racing the show’s “reasonably-priced car”, he screwed up his face. “It’s not really my thing,” he said. “It’s seen as the typical celebrity thing to do and I’m not a celebrity in any way.”

Martin’s break-neck journey towards this intriguing, anti-celebrity celebrity began in a poor suburb of Grimsby. He arrived too quickly for his father, who had popped out to pick up some lorry parts and missed the birth. Ian Martin was a mechanic, too, and would have four children with Rita Kidals, the daughter of a Latvian Nazi conscript who had escaped to England. Soon after Guy’s birth in 1981, the family settled in a small house outside Grimsby, where his parents still live.

Ian was a successful privateer and an Isle of Man TT veteran, but would sometimes have to sell prized bikes so that he could fix the windows. He worked all hours, and passed that ethic to his son, who started tinkering with trucks aged just 12. At the same time, Guy’s “quirky” local school, with its hands-on approach to learning, gave flight to a natural curiosity. But he was no academic, and soon trained formally as a lorry mechanic while bike racing in his spare time.

He now works full-time for Moody International, a Scania centre in Grimsby. “What am I good at? I’m good at MOTs,” he said in Guy Martin’s Passion for Life, a TV series Woodroffe made for Channel 4 last year (the pair have worked together on all Martin’s shows). “I think I’ve had more satisfaction from having a 100 per cent pass rate than I’ve had from any motorbike race.” Andy Spellman, Guy’s agent since 2009, says Martin never takes more than a week or two off work at a time. “Then he’ll come back and go into work at 5am to make up for it.”

Later this month, Martin will down tools to go to the Isle of Man, where he inherited his father’s love of the terrifying road race. He came second last year, four years after a crash at 170mph left him with broken vertebrae and his bike in flames. He has the second fastest lap time, but has a reputation as an outsider in the paddock. He likes it that way. Last year, he stayed with a friend on the island, painting his house in lieu of rent by day, and doing solo practise laps at night.

When he’s not watching his Rolls-Royce Merlin engine run, mug in hand, or standing up to his elbows in a lorry, Martin satisfies a need to push himself to the limits of risk and endurance (he once collected 21 penalty points on his licence, and is now a keen mountain bike racer). But he started in TV going slowly. In the 2011 BBC series The Boat that Guy Built, he and an old friend restored a narrowboat and navigated England’s canals to learn about the industrial revolution. How Britain Worked followed that theme before Speed with Guy Martin brought back the adrenaline. In two series, he attempted to set records on, variously, a bicycle (he hit 112mph in the slipstream of a truck), a toboggan and a hovercraft.

“Once you’ve had a near-death experience and get flooded with dopamine and adrenaline, nothing comes close to that high, and he tries to seek it again,” Woodroffe says. “But he’s not stubborn, or reckless, he’s calculating.” He is also reportedly very smart, with a wit as fast as his TT bike. While he was trying to break a motorbike hill-climbing record in America for the Speed series, he stuffed a copy of Animal Farm down his leathers in case he got lost and had time to kill. He listens to Radio 4 while fixing trucks, and is a fan of Woman’s Hour and The Afternoon Play. He drives a Transit van, and lives with his Labrador, while staying in touch with his girlfriend, who works for a publisher in Dublin. Martin’s ease on camera should not be mistaken for enjoyment of TV. “He wouldn’t give two hoots if it went away tomorrow,” Woodroffe says. “It’s just a channel for his enthusiasm. Being able to help restore a Spitfire is only going to happen in the world of telly.” Spellman says he and Martin turn down ideas almost weekly, but wouldn’t comment on the Top Gear rumour.

Martin would bring the broken show a personality that the BBC should be crying out for – an antidote to Clarkson, Hammond and May’s pally Chipping Nortonism. He has a ready-made fanbase (his autobiography was the second biggest-selling memoir last year, despite barely any reviews) but he remains an enthusiast rather than a presenter. Fame does not suit him well, and when he struggled with it at first, doctors diagnosed Asperger’s syndrome, a form of autism that can make social interaction difficult.

He may yet find a way to the Top Gear track – and has not ruled it out in ambiguous Facebook posts – but for now it is hard to imagine him in a crowded studio, reading from an autocue. “I’ve had my eyes opened to so many things,” he said last year. “But still all I really want to do is my truck job. It’s like an ingrained, default setting.”

A Life in Brief

Born: 4 November 1981, Grimsby

Family: Father Ian was a TT motorbike racer; mother, Rita Kidals, the daughter of a Latvian Nazi conscript

Education: Attended Vale of Anholme school, before training as a lorry mechanic

Career: Secured 18 TT podiums in a stellar career lasting more than a decade. Still works as a truck mechanic, despite a spate of successful TV work

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks