The Big Question: Why is Braille under threat, and would it really matter if it died out?

Why are we asking this now?

This week marks the 200th anniversary of Louis Braille's birth on 4 January 1809. He was the inventor of the embossed system of type that is now used for reading and writing by blind and partially sighted people all over the world. Texts from almost every known language have been translated into Braille from Albanian to Zulu.

So what is the problem?

Braille is under threat from new technologies such as voice recognition and talking computers that can "read" text. It is not being taught widely in schools, is not popular with parents of blind children, and social services departments often do not have the budget to help adults learn. It is feared that, without a campaign to save it, Braille could become redundant.

Why does this matter?

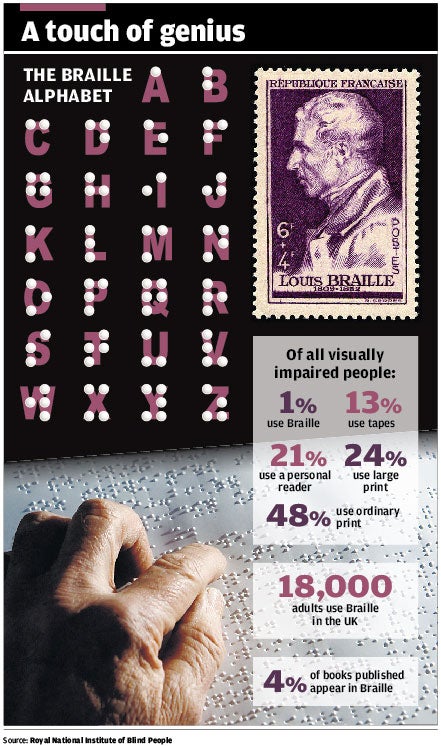

The more blind you are, and the longer you have been blind, the more essential it is. Experts liken the invention of Braille for the blind to the invention of the printing press for the sighted. Although computers and the internet are now the tools of choice for millions of sighted readers, none has yet dispensed with pen and paper. Of 500,000 people in the UK who are registered (or registrable) as blind, around 50,000 have no alternative to Braille, ie their sight is so bad that they cannot manage with large-print books. Of these an estimated 18,000 are current users of Braille

When did Louis Braille invent it?

In the 1820s, when he was just 15. The young Louis went partially blind after injuring an eye while playing with tools in his father's workshop. Later the second eye became infected from the first and he suffered total loss of sight. His father worked as the village saddler and the family lived in the small town of Coupvray, near Paris. They were not well off but a local landowner recognised that Louis was intelligent and arranged a scholarship for him to attend one of the first schools for the blind in the world, The National Institute for the Blind in Paris.

Where did Braille get the idea from?

In 1821, while he was a pupil at the school, he attended a lecture by Charles Barbier, a captain in Napoleon's army, who demonstrated his system of "night-writing". Relying on touch, it used a coded system of raised dots to send and receive messages at night without speaking or using light. It was developed at Napoleon's behest. He wanted a way for his soldiers to communicate without alerting the enemy.

What was wrong with 'night-writing'?

It was too complicated for soldiers to learn and was rejected by the military. But Louis quickly realised its potential for the blind. The major failing was that it was not possible to encompass the whole symbol without moving the finger, so it was impossible to move rapidly from one symbol to the next. Louis set about refining it into the now familiar system of pinpricks, using six dots to represent the alphabet.

How does it work?

The six dots are arranged in two columns of three each, which may be raised or flat, giving 63 combinations, which are used to represent the letters of the alphabet and punctuation. Braille is read by passing the fingers over each character – a key benefit being that each character can be read using a single finger tip without re-positioning.

More advanced Braille, employed by experienced users, is a form of shorthand where groups of letters are combined into a single symbol. With both hands a Braille reader can read 115 words a minute compared with an average 250 words a minute for a sighted reader.

What is its main drawback?

That it is difficult for the sighted to use it. This is why, for almost its entire history, it has been under threat. There has always been a technological development just around the corner that would make it redundant. When Louis Braille died in 1852, aged 43, his invention would have been lost but for the determination of a British doctor, Thomas Armitage, who with a group of four blind men founded the British and Foreign Society for Improving Embossed Literature for the Blind. The organisation later became the Royal National Institute for the Blind.

Is Braille becoming more widespread?

Yes. Although books are available in audio form, there is no alternative to Braille for the blind who want to read a menu, sing a carol, write a phone number down or make a speech. Driven by anti-discrimination legislation, large organisations are increasingly recognising the need to provide Braille translations in lifts, on menus, in hotel rooms and for bank statements.

What about in schools?

Blind children are increasingly integrated into mainstream schools which is better for their development than to be isolated in schools for the blind. But the expertise present in schools for the blind has not always been transferred with them. In addition, some parents oppose the teaching of Braille to their children because reading with the hands looks strange and they fear their children will be stigmatised. Many prefer them to use large-print books because even though they may struggle they will at least look "normal".

Who is the most famous user of Braille?

The best known is probably former Labour Home Secretary David Blunkett. He described to the BBC yesterday the difficulty of learning Braille as a child in the 1950s – which in those days had to be written from right to left so that when the paper through which the holes were punched was turned over it read conventionally from left to right. Despite the difficulties he said it was a "liberator" which ultimately led him to one of the highest offices in the land. Today he faces a new challenge – finger ends burnt by cooking and damaged by rough use in the garden have lost their sensitivity. "But I still plough on," he said,

Did it help his speeches?

He believes it did – by forcing him to extemporise from notes rather than reading a written version. He admits that he found reading statements from the Despatch box a trial because they had to be delivered verbatim – but making a speech was a different matter. Braille helped him master the art of oratory.

Was Louis Braille honoured for his invention?

Not until 100 years after his death. He spent his life in the Institute, teaching Braille to students and translating books. But when he died – of tuberculosis contracted in his twenties, probably aggravated by poor and damp living conditions – he had no idea it would one day be used worldwide. In 1952, his achievement was finally recognised, his body was exhumed by the French government and re-buried in the Pantheon in Paris, and he has since been celebrated as a hero for all blind people.

Is it vital that Braille be kept alive?

Yes

* It is an irreplaceable means of communication for people who are totally blind

* There are almost 50,000 people in Britain who have no alternative to Braille, and many more worldwide

* For reading a menu, operating a lift, finding where things are in a hotel room, there is no alternative

No

* It cannot be used to communicate with, and is not understood by, most sighted people

* Computers are getting better at translating the spoken word into text and vice versa

* Parents are worried that children who read with their fingers may be stigmatised

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks