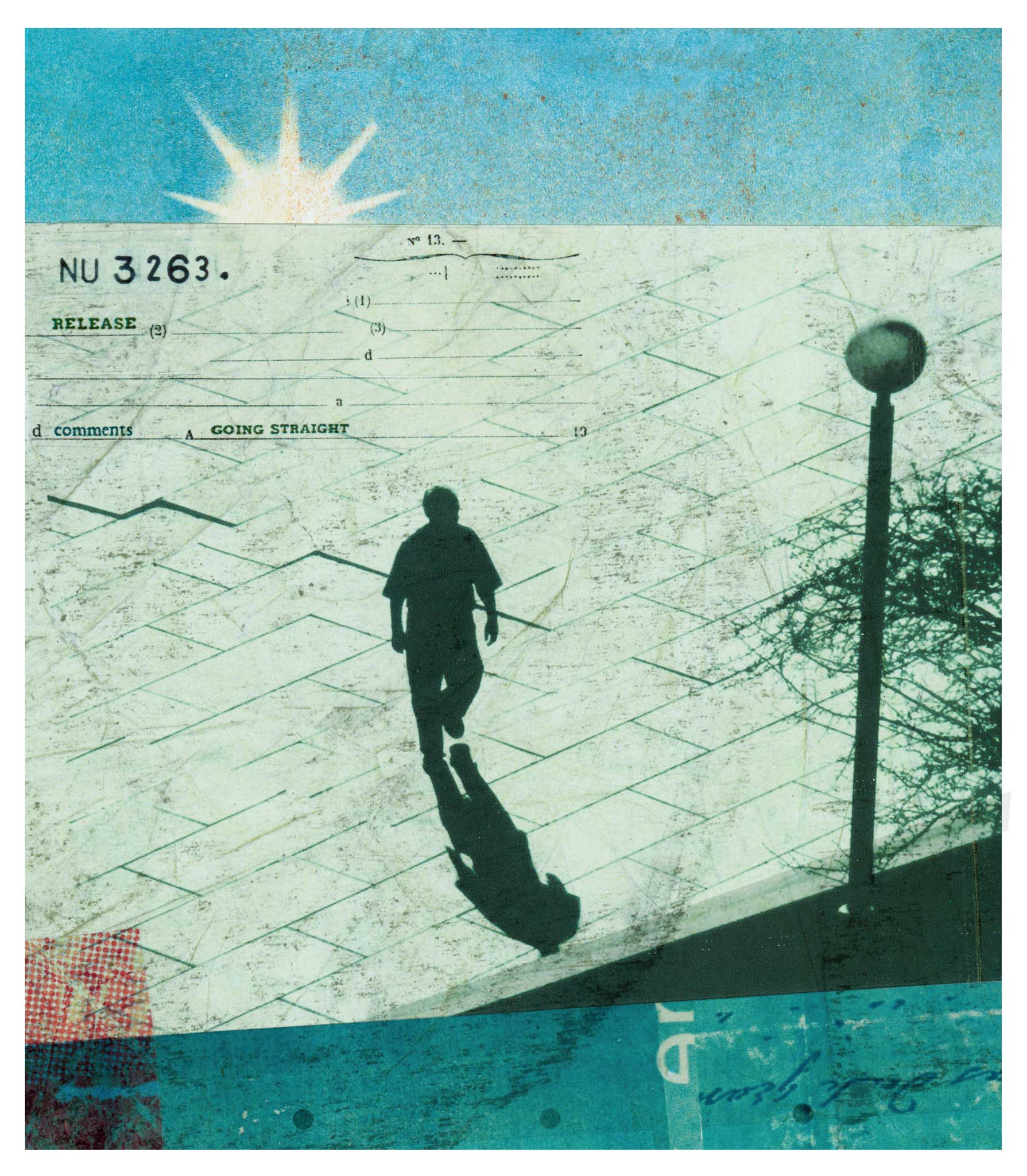

Breaking the cycle: A young offender describes his attempts to go straight after leaving prison

Half of those leaving British prisons find themselves back inside within a year. Here, an anonymous young offender from London describes the high hopes he had on his release – and what happened next.

I was carrying most of my worldly possessions in two black holdalls. A prison officer was escorting me to the gates, and to freedom. I could feel the strain of the holdall straps pulling down on my shoulders. Just like my anxiety. After 18 months behind the door, I was tantalisingly close to that optimistic vision I had been nurturing of my future – gaining a degree and pursuing a career.

Most of my family have been in custody at some point in their lives. My brother has been inside. My uncle and cousin were once on the same prison landing as me. My father turned his back on crime 20 years ago, but he left footprints that did not wash away with the tide. He couldn't stop me from making the same mistakes.

Full of youthful bravado and defiance, I was attracted by the allure of a fast life fuelled by 'easy' money. My dreams lay on the same street corners in east London where my dad had once sold drugs. Children from middle-class homes progress on to university, but crime is the rite of passage where I come from.

Now, though, at the prison gates, my plans were taking me into unknown territory. No one in my family had been to university, but I had been bold enough to think that if I could succeed, I might just be a trailblazer for the next generation and redirect them into higher education.

I was confident that I could do well. I had an unconditional place to read for a degree in journalism, a scholarship from the Longford Trust to help me pay my way, and accommodation sorted out. So why was I anxious?

Despite the volatile nature of life in prison – the drugs, the violence, the unpredictability of others – my life inside had been certain. Unlike my experience of what lay beyond the gate. Having spent a considerable amount of my youth in custody, I had grown accustomed to the prison regime, and had made the most of it. Jail had never been my problem. In some ways, it afforded me a security and a sanctuary away from the chaos I had grown up in outside. So as I stepped out of the gate, on to the tarmac, on the right side of freedom, I found myself beset with fear. And I felt very alone.

But there was my sister and her two boys waiting for me, with broad smiles. My younger nephew was 17 months old. It was the first time I had set eyes on him. He looked up at me and something shifted inside me. I recognised something in his gaze that I had not seen during my time in custody: love. In that moment the loneliness lifted.

As part of the conditions of my release, I had to be supervised by probation for the remainder of my sentence. As we drove through the dense traffic to my first probation appointment, I looked out of the car window at how nothing had changed.

At my old stomping ground, time had stood still. A coke-head was trying to look inconspicuous as he scored from a pubescent dealer. "I'm never going back," I thought to myself – back to the drugs that soothed my torment and shame, back to the guilt that had always been with me.

In prison, I had struggled to come to terms with my offending and with my identity. Who was I? Was I essentially a bad person? Or were my actions those of someone who had played the cards that life had dealt him badly?

There have been times in my life when If have shown a glimmer of the man I can be – thoughtful, loving and intelligent – but too often that has been lost because of the self- destructive choices I have made.

My sister was insisting that I forget about the supported accommodation I had lined up, geared towards helping ex-prisoners readjust to being back in the community. She wanted to support me and suggested I stay with her instead until I found my feet. Confounded by my need to please, and by short-sighted justifications about being close to my family, I disregarded my doubts and agreed.

Although I am close to my sister, I have in the past tested her love to the limit. She had suffered the intrusion of police raids of her home, the indignity of being strip-searched, and of being treated with contemptible suspicion by prison staff when she came to visit me inside. More than anyone, she had shown an unfaltering faith in me. But now I felt she was using my guilt to manipulate me so as to maintain the balance of power in our relationship in her favour. I could never say no to her. Rightly or wrongly, I felt I owed it to her to say yes to coming home with her because of all the hurt I had caused her in the past.

The first few days were great. I spent time with my nephews and I ate well. However, this family home was claustrophobic. The people I love the most, the family I had yearned to be with every day when I was inside, were also the most difficult people to communicate with. I had so much I wanted to share with them about what I was feeling, yet I was emotionally constipated. At times it seemed as if DNA was all we shared. Being part of a family was overwhelming.

Then, what I had thought would be a simple call to confirm my place at university led to all my plans starting to unravel. The admissions department informed me that they had reservations about admitting me because of my convictions, despite the fact that, when I applied while still in prison, I had been completely honest and open with them about my past.

I was distraught and angry that all my hard work suddenly seemed to be in jeopardy. I hold dear to my heart the premise that education is the leveller of all men, that it has a redemptive power which acts as a springboard to overcome social exclusion. Yet here I was thinking I had fallen at the last hurdle. Perhaps I was being oversensitive, but that, combined with my low self-esteem, conspired to break my spirit. I convinced myself that I was not worthy of the new life I aspired to live and headed off down a dead-end highway.

Rather than reach out for help from my family, friends or the trust supporting me, I became insular and dejected. In prison, I had felt like somebody. I was appreciated and regarded in a positive light. Here, in the community, I was inconsequential. As an ex-offender, it was as if I had a social form of leprosy.

Even my family appeared to have reservations about my commitment to change. They had, after all, seen me self-destruct countless times before. They tried to intervene, but their encouraging words were drowned out by my own pessimism. Within a week of being released I had regressed to where I had been, emotionally and mentally, before I went to prison. Everything seemed futile.

Eleven days after leaving prison, I paid the obligatory visit to probation. I sat in the foyer waiting for my appointment, watching the receptionist handle the irate queries from addicts wanting their methadone prescription: all the dregs and strays under one roof, I told myself. It was a demoralising measurement of where I now stood.

During my appointment I was told that my probation officer had a professional duty to inform Social Services that I was staying at my sister's house, because she had children. I took this as an insinuation that I posed a risk to my nephews and became very defensive. This was my family. I recoiled from the idea of Social Services getting involved because of me. I couldn't allow that, so I said I would leave her address, but to go where?

Filled with anger, I went out and bought a bottle of brandy in an attempt to anaesthetise my depressive state. The heat of the liquor evaporated my inhibitions. My thoughts turned to an old debt. It was something I had decided not to pursue once out. I had wanted to move on from that chapter in my past.

A tense telephone conversation with my former acquaintance ended with me demanding repayment. As the mist descended and clouded my judgement, I rang him again. With each unanswered chime, I grew more enraged. Anger, frustration and rejection compounded in an explosive act of irrationality. I went to his flat and kicked his front door off the hinges.

Then I had a sobering thought. "What the hell am I doing?" I walked away briskly, pearls of sweat and shame and remorse forming on my brow. But a neighbour had reported the disturbance.

I was aware of first a police car, and then a police van. My criminal instincts should have produced a sharp urgency to get away, but my wits were blunted. The car drew close and resignation swept away any idea of flight. As the officer stepped out, I swallowed hard. I knew my fate.

Being back in custody has been tough. I entered a tunnel of self-loathing and it took all my resolve to make it out of the other end. I hesitated to make that first phone call to my sister. I had her hurt all over again. She can't understand what went wrong and why.

Back inside I was news – for a minute. Staff and inmates had had high hopes for me, but here I was back again. The spotlight, though, quickly moves on as the revolving door at the prison gate brings back the next person.

I am not even sure how newsworthy someone coming back into custody is. Two-thirds of all those released go on to reoffend within two years. It happens so routinely that lifelong prison numbers, akin to national insurance numbers, are given to offenders.

Some inmates have no desire or intention of changing. Prison is their equivalent of trying to dodge the Inland Revenue. But the Revenue catches up with you sooner or later, and so does prison. There are men who, not for the want of trying, just keep coming back. Men like me.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to this. I know I need to be held accountable for my actions. I expect no less. Ultimately, responsibility for their own rehabilitation lies with the individual, but no man is an island and we cannot do it alone. Change, I have learnt, is the easiest thing to desire, but the hardest to achieve.

The writer wishes to remain anonymous

One individual's story, or part of a broader pattern?

Those released on parole and then recalled to custody to complete their sentence make up 6 per cent of the prison population, which stands at 85,000 in England and Wales, and 8,000 in Scotland. The numbers of those recalled to custody rose by 5 per cent in the year to June 2012, and by 422 per cent between 2001 and 2012.

The percentage of adults who are reconvicted within a year of being released is 47.5. For those serving sentences of less than 12 months, this figure increases to 57.6 per cent. And with 18- to 20-year-olds, it is 58 per cent.

In the case of 37 per cent of prisoners, another family member has been found guilty of a non-motoring criminal offence. They are more likely (59 per cent) to reoffend within a year than the average (47.5 per cent).

14 per cent of men and 16 per cent of women in prison are serving sentences for drug offences; 55 per cent of all prisoners report committing offences connected to drug-taking.

In 2007-2008, reoffending by all released ex-prisoners cost the economy between £9.5bn and £13bn.

All figures from the Prison Reform Trust's Bromley Briefing (November 2012), prisonreformtrust.org.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.