Even in the dock, Constance Marten and Mark Gordon were caught up in their own toxic world of delusion

While sentencing the couple to 14 years imprisonment for killing their daughter, Judge Mark Lucraft KC said neither Marten nor Gordon gave much or any thought to their baby, adding that their focus was entirely on themselves. David James Smith explains how their strange bond didn’t falter as the darkest chapter of their long and complex history was laid bare

The outsiders, the outlaws, the seemingly unlikely subjects of a nationwide manhunt, do not yet know it, but they have already spent their last night together for a long time to come. It is 27 February 2023 and, driven by desperation, the couple have come down from their hideout in the hills near Brighton and back to civilisation, in search of food. She goes into the convenience store, picks up a tin and puts it in her pocket to steal it.

She changes her mind, takes it out and puts it back. She goes out to the cashpoint, makes a withdrawal from the account containing her trust funds and goes back in to buy some provisions. He is outside waiting, hood up. He is limping badly, using a stick, his shoeless foot is wrapped in plastic after sustaining an injury back up in the woods.

The couple have been on the run for the best part of two months, trying to stay one step ahead of social services, her family and the police. But now the game is up. Someone has seen them and called 999. The police arrive. She claims her name is Arabella. But they already know that’s a lie.

Later, while being questioned, he will tell the police, “My wife is a beautiful, intelligent woman”, but for now, all the officers care about is, “Where is the baby?” He asks for food. The police want to know, “Where’s the baby?” The couple aren’t saying.

All he cares about is food. They tear open a packet of crisps from the shopping and lay it out on the ground. Handcuffed, he kneels down and snatches at them with his mouth and teeth, grunting at the ground like a feral creature.

An officer notes the unwashed, stale odour around them both. They smell like homeless people, he thinks. But that’s hardly surprising – they are homeless people. Stressed, paranoid and dishevelled, they are bound tight, even as they know the time has come to part.

“Daddy bear!” Constance Marten calls to Mark Gordon. “Daddy bear.” Not once, not twice, but three times. “Daddy bear.” She appears to be trying to reassure him.

He calls back, “Love you, babe.”

She says, “I love you.”

“Be good,” he says, “I love you forever – forever and ever more.”

She replies, “You too. I love you, baby.”

They seem like deranged lovers; a sort of Folie a Deux caught up in their own world of delusion. Crazed by deprivation and hunger, demented by recent and past events, and by the certain knowledge that the world has been looking for them.

Where’s the baby? The baby, their fifth child, Victoria, lies in a polypropylene bag, in an allotment shed with broken windows up the hill, where the police will come across her four days later. The couple do not disclose where the baby is, but the police find her dead, decomposing. Her tiny body is hidden beneath soil, as if it had been a portable grave, a mobile interment, not just soil, but assorted detritus; a few pages from The Sun, a rolled-up jacket, some empty sandwich wrappers and a bottle of petrol.

They were out of their minds, Marten told the jury at her first Old Bailey trial. “We were in a state of indecision, of fear and panic.” They thought of burying Victoria; they bought petrol and thought of cremating Victoria, like the burning ghats that Marten had seen in India.

They thought of jumping into the fire and ending their lives with her. They didn’t know what to do, so they carried their daughter around in the bag until she became too heavy, and then they began leaving the bag in the allotment shed. Victoria was still wearing a soiled nappy when she was found. Marten couldn’t bear to change her dead baby’s nappy, she said. The prosecution accused her of denying dignity to baby Victoria, even in death.

“You left her in a plastic bag, sitting in her own faeces?”

“Please, don’t put it like that.”

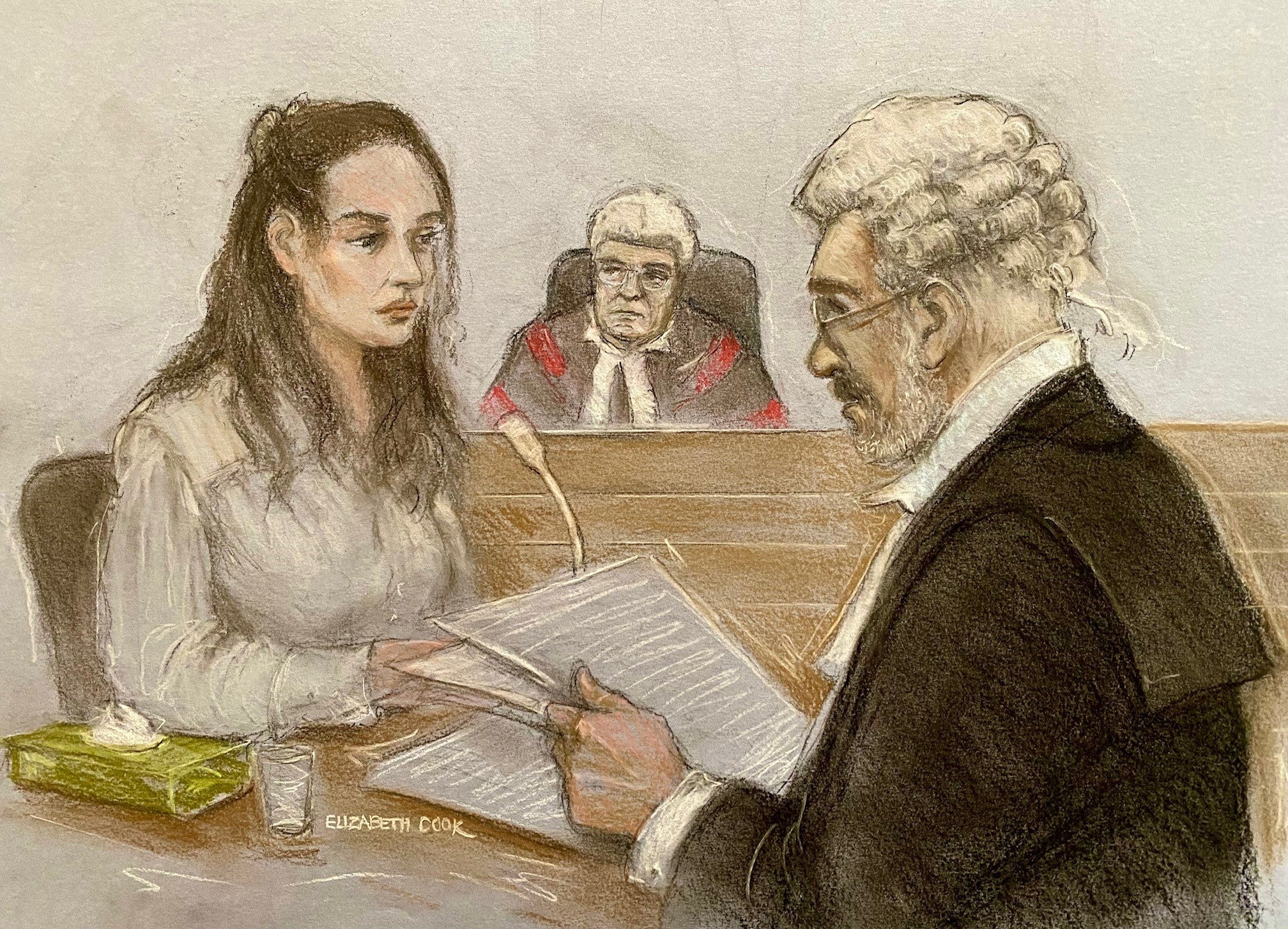

Baby Victoria’s body was so decomposed that neither the cause of death nor the date of death could ever be scientifically known. Onto that blank page, a dark story could be written; a long and complex history, bound up in the lives of this seemingly ill-matched couple, who after their long parting on arrest and charge, were reunited for the first trial in the dock of Court 5 at The Old Bailey in January 2024, at the beginning of what would prove to be a long and painful legal odyssey, over 19 months and two trials, fraught with tension, disputes and delay.

Transported back and forth each day from their respective prisons, Marten and Gordon often appeared hungry for each other’s company. A dock officer was always between them, but they regularly talked across them as if they weren’t there.

Despite facing long prison terms after a sensational public trial, they still presented like new lovers, smiling at each other, eyes shining, chatting, whispering, passing notes, much to the mounting irritation of the judge.

When Marten refused to see the Crown psychiatrist, the presiding judge, Mark Lucraft KC, said: “My patience with her has been tried many, many times.” As the legal odyssey deepened, Gordon’s behaviour became ever more disruptive and challenging, the judge claiming that between them they were trying to “sabotage” or “derail” the proceedings.

Gordon wore tight-fitting clothes to court, often a pale blue shirt and tie, sometimes over a T-shirt, which on one occasion he pulled up over his face like a mask, apparently in protest because he had been unable to shave. Marten wore white and cream blouses and dark trousers with a scarf or wrap, her long dark hair often tucked behind one ear, her head inclined slightly, paying close attention.

Gordon never gave evidence at the first trial. He had agreed to go into the box one Friday afternoon, but it was decided to delay the start of his evidence until the Monday. By then, he had changed his mind – no explanation was ever given. So the jury never heard from him.

When Marten was called and left the briefly unlocked dock to walk across the court to the witness box, the atmosphere tightened. She had not even completed the oath when she asked for a toilet break and was led back through the dock to the cell area of the Old Bailey.

We sat waiting, the whole court, including, I am certain, the judge, wondering if she would ever return, but she did. She looked ashen. A few minutes into her evidence: “I am so sorry, I get very nervous public speaking. Could I get five minutes?”. The judge gently refused.

She was in the box over many days, her evidence the centrepiece of the trial, her account at times both plausible and heart-rending, on the one hand, and quite fantastic and delusional on the other.

Sitting a few yards from her was her mother, Virginie de Selliers, now in her sixties and a psychotherapist, who had been estranged from her daughter some years ago and made no detectable eye contact.

In one outburst, Marten, the eldest of three siblings, proclaimed, “I had to escape my family, because my family are extremely oppressive and bigoted and they wouldn’t allow me to have children with my husband and will do anything to erase that child from the family line, which is what they did do.”

Later, she spoke of being pursued through the courts by someone in her family, after “I had spoken out about serious abuse by that family member.” The accusation hung there, unexplained.

When the first trial ended without a verdict on the most serious charges, the Crown pressed for a retrial. This year, the couple faced a new jury accused, either of manslaughter by gross negligence or of causing or allowing the death of baby Victoria. This time, there was even greater chaos and delay. Both Marten and Gordon parted ways with their leading counsel.

Gordon began representing himself, questioning his co-accused from the dock, with the aid of a microphone. He complained loudly and often of unfairness in the proceedings. This time, he started giving evidence but then refused to be cross-examined. Marten continued with junior counsel. She gave evidence but terminated her own cross-examination after the first few hostile questions.

Until the moment of their meeting, in around 2015, the contrast between the lives of Marten and Gordon could hardly have been greater. She had grown up in ostensibly idyllic circumstances on a Dorset estate, her grandmother linked to the late Queen Mother, her father, Napier, a page to the late Queen Elizabeth.

As she acknowledged in court, she had come from “a very privileged background”. She was the beneficiary of a trust fund, and although that was subject to limitations, she still had nearly £20,000 in her account at arrest.

The jury at the first trial must have wondered about Gordon’s background and noted that he did not get a “good character” direction from the judge, as Marten did. They were deliberately not told, as it would have been prejudicial to his position at trial.

That changed in the second trial, after Marten made reference to Gordon’s past, and he put his own history in play by alluding to his good upbringing.

He was born in Birmingham of Jamaican heritage. He never knew his father. As a child, he moved with his mother to the United States, first to New York and then to Hollywood and Florida. More than 35 years ago, on 29 April 1989, when he was a boy of 14, he had burgled the home of his next-door neighbour and, with her children asleep nearby, subjected her to a prolonged and violent rape, armed with a knife and wearing a mask.

A few days later, and shortly before being arrested, he had tried to repeat the crime at the home of a different neighbour, hitting the man of the house with a shovel when he was confronted before he could complete the assault.

Gordon was initially sentenced to life imprisonment with no minimum term, but was freed after 20 years and deported back to the UK, where he was registered as a sex offender and obliged to report his whereabouts regularly to the police, which he later failed to do.

As Marten told the Old Bailey, she had met Gordon in an incense shop in east London in 2015. He had not long since returned to the UK and she had trained as a journalist and was considering starting a course at East 15 Acting School.

Marten knew the shop owner who asked her to keep an eye on the only other customer as they briefly left. The customer was Gordon. They laughed about it, got talking, went for coffee and became, Marten said, “good friends”, the relationship only developing after they travelled together in South America, getting married in Peru.

Although this was not in evidence, she apparently came back pregnant, knowing only that Gordon had been in prison in the US but not the nature of the crimes. She learned that from the police in 2017, I have been told.

They seem like deranged lovers; a sort of Folie a Deux caught up in their own world of delusion. Crazed by deprivation and hunger, demented by recent and past events

The Florida records reveal a further terrible incident, disclosed by his mother in testimony at a sentencing hearing. When he was aged four and still in Birmingham, his mother Sylvia Satchell worked as a nurse for Chrysler and left Gordon in a daycare facility where a number of other children at the nursery were targeted.

Gordon’s mother told the court in Florida that the abuser went to prison “for a little while,” but it isn’t hard to see that behind the tragic death of Victoria lay a story of a cycle of physical and psychological harm that will sadly stretch further into the future.

Gordon and Marten had five children together. The first and second children were taken into care in 2019 and the third and fourth children were subject to Emergency Protection Orders after their births in 2020 and 2021.

The couple turned up in Wales in 2017, living in a tent as she went to hospital to have her first baby. She gave a false name and pretended to be an Irish traveller – maintaining the accent even as she gave birth. Gordon turned up and when challenged on his false name he became aggressive. Police were called and he was charged with assaulting multiple officers and went briefly to prison.

It was never suggested by their evidence or from their behaviour in court that Marten was in any way under Gordon’s influence or control. In fact, for much of her testimony, it seemed that she was fully invested and often driving their haphazard plans.

There was, however, a jarring episode that emerged in the potted history of their interactions with social services and the family courts that was summarised for the criminal trial. A family court judge had ordered their oldest two children to be taken into care in 2019 after finding that there had been a single but dramatic episode of domestic violence.

According to Marten, she had accidentally fallen out of the window of their apartment. She ended up in hospital for eight days with a ruptured spleen. She vehemently denied that Gordon had pushed her out, but that was what the family judge found.

There was no evidence of coercive controlling behaviour by Gordon at the trial and it was certainly not reflected in Marten’s account or her demeanour.

Instead, she said she had “slept with the devil” when she engaged with social services. She loved her children – the couple had four children, before Victoria, and all are now in care – she had been an excellent mother to them, she said, and she would do anything to get them back.

In court, she blurted out that her two youngest children had recently been removed from foster care after allegations of physical abuse by the male carer. It turned out to be true – confirmed by police inquiries. There was apparently no end to the tragic cycle of events.

Marten claimed: “The problem I had was I was not just up against social services but family members who were very influential with huge connections in high places, including parliament, if they said to social services jump, they’d say how high.”

It was against this backdrop, she suggested, that the couple had gone on the run in December 2022, giving birth to baby Victoria at a cottage in Northumberland, by her account, on Christmas Eve, going on the run, hiding the baby to prevent her being taken into care.

Perhaps too, Gordon’s juvenile convictions played a part in their outlaw way of life and in the attitude of the authorities towards them.

Marten and Gordon’s paranoia was high. Marten told the court that family members had hired private detectives to pursue them. There had been private investigators – two teams apparently - but that was sometime earlier.

She alluded to the belief that the detectives might have tampered with their cars, after one broke down and the replacement caught fire on the M61 near Manchester. That was on 5 January 2023, when the police found baby Victoria’s placenta and the high-profile nationwide search for the couple began.

Marten and Gordon kept to taxis after that, spending £100s on fares as they zigzagged across the country, trying to stay ahead of the police and the publicity.

It drove them further and deeper from the world. With the tragic end on the South Downs on January 9th, 2023, when Victoria was just 16 days old.

Despite the seriousness of the charges, in court it felt, at times, like the case had become a trial of Marten’s mothering – “aggressive, bullish”, as Marten’s KC, Francis Fitzgibbon, put it in his description of the way the case had been pursued in the first trial. Questions were often repeated over and over in their cross-examination of Marten; she didn’t carry her baby properly or support its neck. She didn’t dress the baby properly, she didn’t feed the baby properly, she let the baby get too cold. What was the baby doing in a tent? Why wasn’t she at home in the warm?

On Marten’s account – her consistent version of events – she had breastfed the baby, while sitting cross-legged on the floor of the small tent in which they were living, Victoria resting and finally sleeping on her lap. Marten would say she fell asleep too, exhausted, and slumped forward over her baby.

“She wasn’t moving when I woke up. I don’t know how long I’d been asleep. I saw she wasn’t moving and her lips had gone blue... I tried to resuscitate her for like, well I tried to breathe in her mouth and pump her chest. There was no response. I cradled her... I didn’t know what to do.”

She told police she held her like that for hours. “I think Mark was telling me that I had to let go because it’s not good to hold her like that, because it probably wouldn’t be good for my state of mind, so I wrapped her up in a scarf and then I think we put her in a bag. I didn’t know what to do after that.”

They could have dialled 999, of course. But they were outlaws together, alone again, just the two of them, unable to rise above their fate.

They are now facing further years of separation, in prison, after both were convicted of the gross negligence manslaughter of baby Victoria by the second trial jury. The first trial had convicted them of concealing the birth of a child, child cruelty and perverting the course of justice.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks