How could three tourists have been battered within an inch of their lives by a burglar in the plush London Cumberland hotel?

Mary Dejevsky listens in court as a dark, disquieting side of the capital is revealed

Fatima al-Najjar arrived at Heathrow from her home in the United Arab Emirates in the middle of a Saturday evening and reached her hotel at around 11pm. Barely two hours later, she was lying on the floor of her seventh-storey room, her eye sockets shattered, the side of her head smashed open, her life ebbing away. She was one of three sisters from the UAE who were critically injured by a hammer-wielding burglar almost before their family tourist and shopping trip to London had begun.

I have been appalled, but also fascinated, by this horrific case ever since the news broke on the Sunday morning, 6 April, when I started to follow it. But it is hard to explain why. There are plenty of dreadful crimes around; why this case and not others?

There was, of course, the sheer viciousness of the attack on three women in their beds, and the fact that three sisters who had come with their children and other members of their family to enjoy London, like so many do, had their holiday cut short so precipitately and so brutally. And there was the contrast between a crime of such violence and the location: The Cumberland hotel, a well-established four-star hotel just off Oxford Street in the very centre of London. Such things just don't happen here, certainly not in those sorts of surroundings… do they?

There was also some rather awkward diplomatic fallout, which flickered briefly into the news, and out again. The fate of the Najjar sisters prompted an outcry in the UAE – as it was bound to do. However rare, unique even, such an attack on foreign visitors to London might be, a crime of such magnitude cannot be hushed up – although it seems to me that the case has not always received the headline treatment it deserved and that fears for London's multibillion-pound tourist industry might offer part of the reason.

That, though, is by the by. Soon after the attack, the UAE's foreign ministry issued a warning about the incidence of violent crime in the UK capital. It was the sort of travel advisory that the Foreign Office here issues to discourage people from venturing into war zones and other risky places. Needless to say, the warning did not go down well in Whitehall and – it is said – representations were made to the UAE about the desirability of avoiding negativity among friends.

Not that you can really blame the Gulf state. If three British tourists, all women, had had their skulls shattered in the supposed safety of a luxury hotel somewhere in the Gulf – and in front of their children – then a similar warning might well have appeared on the website of the UK's Foreign Office, too.

My main reason for following this case, though, was because the crime seemed so senseless and the violence so gratuitous. Why were three Arab women bludgeoned to near-death in a London hotel room in the early hours of a Sunday morning? Who could have committed such a crime, and why? In the first few days afterwards, all manner of theories were hazarded. There were those who suggested, on the basis of no evidence at all, that the women had played some part in a drugs deal that went wrong. Others speculated that they were attacked because of a vendetta imported from their home country. Still others thought that the two sisters who had arrived earlier may have been identified by (foreign) criminal scouts as high spenders and followed to their room. Any theory, it seemed, was preferred to the possibility that this was a crime born and bred in London and that the Najjar sisters were the most blameless of victims.

Yet at the preliminary hearing in July, this is exactly how it appeared: a banal crime committed by one drug-dependent loser, abetted by another, with half a dozen petty criminals playing bit parts on the side. Remaining to be convinced, I spent much of the past two and a bit weeks at Southwark Crown Court as the evidence was heard in the case of the Crown vs Philip Spence and Thomas Efremi.

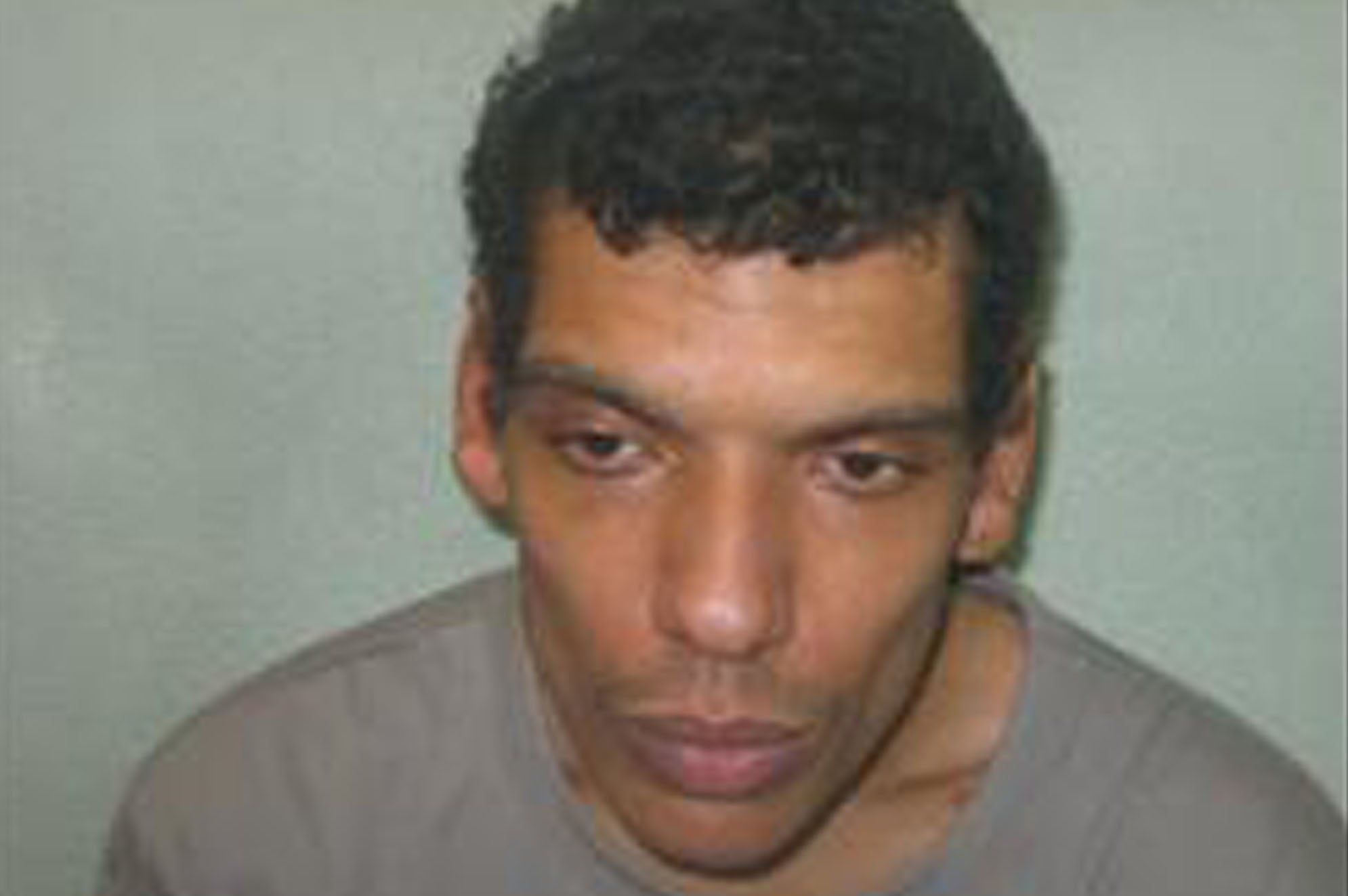

They made an odd couple in the glassed-in dock, very odd. Spence, tall and rangy, but most of the time hunched over, came across disconcertingly as a modern-day changeling. In profile, he looked white; face-on, he looked brown. If you had shut your eyes as he mumbled his evidence, you would have assumed that he was black. On the stand, he was asked about his background. It turned out that he had an Italian mother and a Jamaican father. He had also, he said, been excluded from school at the age of six and muttered something about sexual abuse.

Efremi, much shorter and squarer, hobbled in on a single crutch, but was by far the more dynamic, periodically shaking his head or laughing scornfully as he listened to some of the evidence. Not a well man, he was rushed off to hospital one morning, suffering from high blood pressure, but had recovered enough to return the next day.

By the time of the trial, both had already pleaded guilty to lesser charges. Spence had admitted three counts of grievous bodily harm and aggravated burglary just before the trial. Efremi had admitted one count of fraud – which entailed cruising cash machines in the hours after the attack, using one of the women's cards to steal a total of £5,000. He had got this plea in early, in the hope of a lesser sentence.

Given the gravity of the case, however – and perhaps its sensitivity for UK-Gulf relations (while recognising, of course, that politics never, ever intrudes into justice in the UK) – the prosecution wanted to nail the two on more serious charges. Thus, Spence was up on three counts of attempted murder and both of them for conspiracy to commit aggravated burglary. And securing these convictions is what the barrister for the Crown, Simon Mayo, QC, set out to do.

When Fatima al-Najjar appeared in the witness box, the second sister to testify, her resilience seemed remarkable. She spoke good English and came across as a self-possessed young woman, as had her elder sister Khulood, who appeared before her. It was hard to reconcile her demeanour with what she had been through. Yet, after she left the courtroom, loud sobs could be heard.

Khulood remembered waking up to see someone in the room she was sharing with her sister, rifling through some of their belongings. He approached her, she says, and asked, "Where's the fucking money?" But before she could reply, he had started hitting her. She did not know what with, only that the blows were heavy and to her head, before she lost consciousness.

Fatima recalled waking up in the dark to the screams of her sister, and trying to get in the way of the attacker to defend her. But the blows now rained down on her, too, and she fell to the floor, unconscious, in a pool of blood.

The most savagely attacked was the middle sister, Ohoud, who was asleep in the adjoining room with one of Khulood's children. She remains in hospital and could be bedridden for life. The surgeon who oversaw her treatment testified that, at best, she would one day be able to operate an electric wheelchair with the small part of her brain that remains intact, but he was not hopeful.

A paramedic who was among the first on the scene described Ohoud's skull as having been shattered "like an egg", with a golf-ball-sized section of the brain protruding. The surgeon said that her jaw had been cracked in two and the damage to her mouth could be explained only by a blow from the claw end of the hammer. All the emergency staff who testified, many of whom had extensive experience, were adamant that they had never seen such injuries before, and would never forget them.

Testifying over a video link from the UAE, Sheika al-Mheiri, a half-sister of the three, who had been staying in another room, could not hold back tears as she described coming across the scene, just minutes after the attack, and concluding that Ohoud was dead. She could not believe that the young woman could survive with the injuries she had sustained. There was blood everywhere, on the beds, on the floor, on the walls. One of the children was standing, traumatised, with blood on her nightdress.

The evidence given by the sisters, and their witness statements, like the medical and police evidence from those who were called to The Cumberland hotel at around 1.30 that Sunday morning, was harrowing to hear. The jury also had photographs and X-ray evidence – one of the prosecution's prime purposes being to demonstrate that the attacker must have known that he could kill them and was therefore guilty not just of GBH, but of attempted murder; intent being crucial to conviction.

Philip Spence insisted, on the contrary, that he had wanted only to stop them screaming, to "make them lose consciousness", he said time and again, so that he could make his getaway with his loot, which was considerable. Quantities of cash and gold jewellery (not all of which has been recovered), plus iPads, phones and bank cards to an estimated value of more than £50,000. Calm as you please, he was shown leaving the hotel by the main entrance, taking the bus to Victoria, and the night bus from there back to Islington, where he handed the bank cards over to Thomas Efremi, who hired a minicab to do the rounds of cash machines before dawn.

Aside from the devastating injuries of the Najjar sisters and the way their lives were shattered in the space of just a few minutes in the early hours of one morning, what else stands out from this case? One is the sheer honesty, professionalism and humanity of those from the emergency services who testified. It was hard to fault any of them. Confronted with true horrors in the night of 5-6 April, they all did their duty in exemplary fashion.

A second is the contribution that technology now makes to policing. Once Spence and Efremi had been identified and arrested – each snitching in the most ignoble fashion on the other – their respective paths over that night and the next morning were traced in minute detail from CCTV and mobile-phone records. Efremi admitted giving Spence the hammer (though not, he claimed, for any nefarious purpose). But he had little choice but to admit this, because his DNA was found on it, when it was recovered from an outside ledge at the hotel.

A third – for anyone unfamiliar with the criminal milieu – is how deeply entrenched the drug culture in parts of London is, and the apparent impunity it enjoys. Spence and Efremi were essentially drug buddies. They regularly used crack cocaine and heroin together (and with others). Efremi said he knew "all the dealers" on his north London estate. He and Spence went shoplifting for meat and sold it on to help to fund their drug purchases. So long as they had cash, they could call in new supplies in minutes. Both had extensive criminal records, but Efremi had been adept at escaping prison, graduating from suspended sentence to suspended sentence. Even when he was hauled up for flouting the conditions, the only punishment seemed to be another suspended sentence. With his conviction for "conspiracy" this week, his charmed life is probably coming to an end. He is now in Wandsworth prison, awaiting sentencing.

A fourth observation relates to security at London's hotels. The Cumberland – a huge hotel, which accommodates 600,000 guests a year – says that there have been no violent incidents nor any thefts reported to police in the 10 years that it has been in its current ownership. In a statement after the verdicts this week, the hotel management – which, perhaps not surprisingly, faces a lawsuit from the Najjar family – expressed its relief and described Spence's evidence as "self-serving and untruthful".

This was a response to his claims that he had visited The Cumberland repeatedly – from his teens, when he had played on the roof with his mates, to now, when he would forage food from trays left by guests outside their rooms and doss down in laundry rooms that had been left open. The hotel categorically rejects this and says that it is "unaware" of anyone using the hotel to doss down in. But it is hard to believe that Spence did not, at the very least, know his way around the hotel. He was also described by Efremi and others as a "hotel creeper" – someone who prowls around hotels looking for things to steal.

It is true that with the Najjar sisters, he struck lucky. All involved admit that they had left the door to their main room ajar, so that the half-sister, Sheika, could come and go. The Cumberland, like most international hotels around the world, advises its guests to lock their rooms. But if Spence was not fantasising when he said that he went to The Cumberland quite often, whether to doss down (as he said) or to thieve (as others said), and if, as he said, he would arrive by the main entrance and take the lift, and had never been challenged, then there might be a problem. You don't want London hotels to have airport-style security, as some do elsewhere, but the occasional request by security to show a valid hotel card might not come amiss.

In the end, though, the chief observation is the most dispiriting. It is that there really was no more sophisticated explanation for this terrible crime than the fury and desperation of a completely inadequate young man, who was addicted to drugs and – as he himself put it – had "a temper". Philip Spence, the judge said after the jury had returned unanimous guilty verdicts on all counts, could now be looking at a "full-life" – ie, life means life – sentence when the decision is announced next month. As he was led out of the dock, his accomplice shook his fist and vowed, "I'll kill him, I'll kill him, if I find him in prison." None of that will be much consolation to a family from another land whose lives have been changed for ever.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.