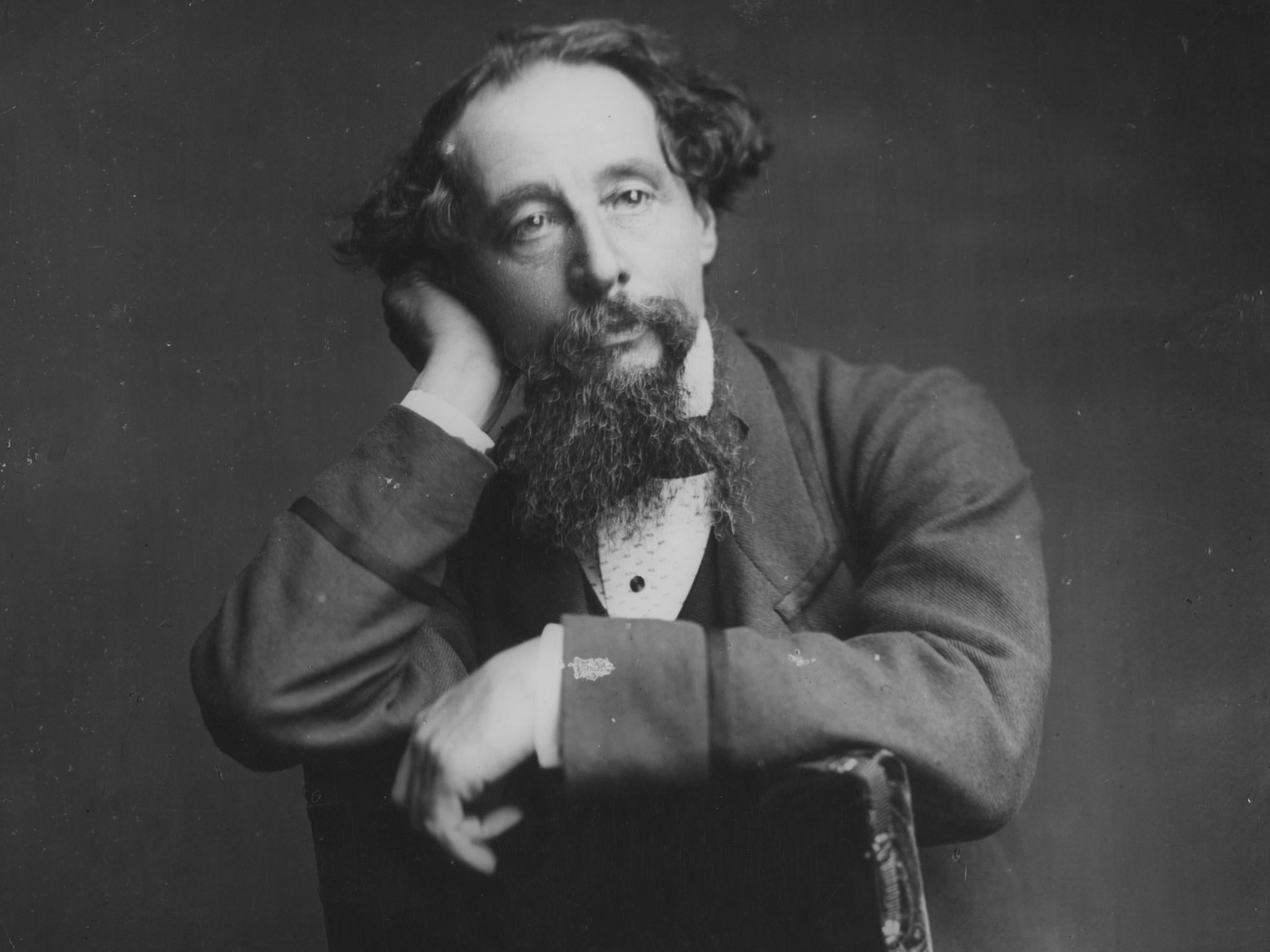

Charles Dickens' All the Year Round: Discovering the fascinating insight into the world of Victorian letters

The identity of the supporting cast of correspondents who sustained ‘All the Year Round’ can now be revealed

After the story of my discovery was broken in The Independent in July 2015, I started to receive a steady stream of diffident inquiries from researchers around the world, anxious to discover the authorship of pieces in All the Year Round about Switzerland, stage magic, dog shows, and Darwin’s theory of evolution.

There was even one from a professional yo-yo artist seeking to learn the identity of the genial writer who introduced a yo-yo into one of his stories (in all but name) some 60 years before the spinning toy was officially invented. (The story is entitled Quite a Lost Art, the proto yo-yo is referred to as “the ivory bandelore”, and it turns out the author was the playwright and translator John Oxenford).

I have patiently answered all these queries, providing the requested names. One elderly male scholar responded with a protestation of undying love, as with three little words – David Thomas Ansted – I was able to fill a lacuna which had for years past hindered him from publishing an otherwise completed research project.

Having set myself the goal of producing a reader’s guide to All the Year Round within two years, my first step was to note down every annotation as it appears in the margins of the journal. Although this is largely mechanical work, it is also very intensive and time-consuming as there are something like 2,500 marginal notes in pencil, accompanying 3,000 articles, stories, poems and serialised novels, spread across 12,000 pages of double-columned fine print.

The notes are often just bare surnames, preceded by “Mr”, “Miss”, “Rev”, or “Dr”, giving us a clue – but sometimes little more than that – as to the identity of the writer. There is no problem, of course, with a name like “Mrs Gaskell”, but who might be the individuals concealed behind such name tokens as “Miss Robertson”, “Dr Brown” or “Mr Jones”?

I started to notice inconsistencies in the way that some contributors were designated. Fair enough that Henry Morley is sometimes referred to by his full name but also appears as “H Morley” and “Mr Morley”. However, do “Rev Dixon” and “Mr Dixon” designate the same person, and what about Messrs (or Mr?) “Harwood” and “Harewood”? In order to make a judgment in these matters it is necessary to look at the content of the pieces and to see if they are stylistically or thematically similar, as well as trying to ascertain from external sources who the person or persons might be.

In the last-mentioned example, I am pretty confident that only one Harwood is intended – the minor novelist John Berwick Harwood – but the inconsistency was a reminder that the inscriptions cannot always be relied upon. Once my basic checklist of roughly 300 named contributors was complete, I started on the far more interesting job of trying to identify the less eminent Victorians whose writing was nonetheless deemed worthy of publication in the bestselling weekly of the 1860s.

One of the first names that caught my eye was “CPA Orman”, with the initials and unusual surname both offering clues. Basic online searches threw up nothing and I began to doubt if the name was accurately recorded. Instead of “Orman” I looked for “Oman” – and found my man. The author of A fair on the Ganges, an atmospheric eye-witness account of the huge annual Hindu gathering on the banks of the great river, was Charles Philip Austin Oman, born in Calcutta in 1825. He spent most of his adult life in the foothills of the Himalayas as manager of an indigo plantation and died in Winchester in 1876. He published one novel – Eastwards, or realities of Indian life (1864) – and was the father of historian Charles Oman and grandfather of the biographer Carola Oman. My online research led me to the Bodleian Library, where I found the Oman family archive, the manuscript of the Ganges article and a note confirming that it was published in All the Year Round in 1861.

This neat circularity inspired me to proceed with my detective work, and what started out as something of a chore soon turned into what is now an all-absorbing pursuit – unearthing the lost lives of Dickens’s previously unknown contributors.

As well as staff writers for the magazine, Dickens had a small group of regulars including the nigh-indefatigable Walter Thornbury, who wrote close to 200 pieces for All the Year Round and Household Words (another Dickens magazine) before dying of exhaustion in a mental asylum at the age of 48. Outside of this inner circle of professional journalists were around 250 occasional contributors, some personally known to Dickens, others drawn to make submissions to the journal for anonymous publication by the name and fame of its conductor, and representing between them the broadest possible cross-section of literate mid-Victorians. While 80 or so remain to be positively identified, I have at least skeleton biographies for all the others – clergymen, teachers, doctors, lawyers, landed gentry, colonial administrators, soldiers and sailors, merchants, naturalists, diplomats, gentlemen and ladies of letters. Even though women would have been deemed ineligible at the time for any of the formal professions, contributions by female writers still comprise about 25 per cent of the magazine’s contents.

One particular contributor stood out – an epitome of British eccentricity. He is designated in the marginal notes to two articles (about snakes and fish) as “Mr Buckland”. I was able to identify this writer as Francis Trevelyan Buckland, born in 1826 as the son of William Buckland, a celebrated clergyman-scholar, who gave the first description of a dinosaur (Megalosaurus) based on the examination of bones and coined the term “coprolite” for fossilised faeces.

He insisted on wearing his academic gown to conduct geological research and, reputedly, ate the preserved heart of Louis XIV after opening up a silver casket during a tour of inspection of precious relics in a stately home.

The house in which Frank Buckland grew up was notable for the miscellany of live and dead animals scattered around the rooms, as well as the surprisingly varied menu, which featured panther and crocodile as well as blue-bottle and mole. Frank received a medical training and was for some years a surgeon with the Life Guards. Alongside his medical duties he pursued a lifelong interest in the study of animals, and like his father was inordinately fond of dissecting and eating them. A vivid pen portrait was given by his medical colleague Charles Lloyd: “Four-and-a-half-feet in height and rather more in breadth – what he measured round the chest is not known to mortal man. His chief passion was surgery – elderly maidens called their cats indoors as he passed by and young mothers who lived in the neighbourhood gave their nurses more than ordinarily strict injunctions as to their babies. To a lover of natural history it was a pleasant sight to see him at dinner with a chicken before him and see how, undeterred by foolish prejudices, he devoured the brain.”

Buckland lamented the narrowness of the English diet and was the founder of the Acclimatisation Society, a body committed to the breeding of exotic species in Britain as food sources. In 1862 he hosted a dinner for 100 guests at which Japanese sea slug, curassow (a large Mexican bird) and kangaroo were served.

A sense of Buckland’s racy style, as well as his chaotic home life, can be gleaned from the following excerpt from an article (not published in All the Year Round) describing his struggle to manhandle a nine-foot sturgeon into his basement kitchen: “I was determined to get him into the kitchen somehow; so, tying a rope to his tail, I let him slide down the stone stairs by his own weight. He started all right, but ‘getting way’ on him, I could hold the rope no more, and away he went sliding headlong down the stairs, like an avalanche down Mont Blanc. He smashed the door open and slid right into the kitchen till at last he brought himself to an anchor under the kitchen table. The cook screamed, the housemaid fainted, the cat jumped on the dresser, the dog retreated behind the copper and barked, the monkeys went mad with fright, and the sedate parrot has never spoken a word since.”

But Buckland also had a more serious side. From 1867 until his death in 1880, he was national Inspector of Salmon Fisheries, charged with both managing a natural resource and overseeing the burgeoning fish-farming industry.

It appears from surviving correspondence and Buckland’s own diary that he and Dickens were personally acquainted, In many ways he was an ideal contributor to All the Year Round; he possessed specialist knowledge which he could communicate in a lively, amusing and even quirky manner, added to which he was a born storyteller.

As a devourer of rare species he epitomises the mid-Victorian rapacity towards the natural world, but he also left a more positive legacy in the form of a substantial endowment which still supports the Buckland Foundation, an organisation devoted to the study of marine ecology and the sustainable exploitation of fish stocks.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks