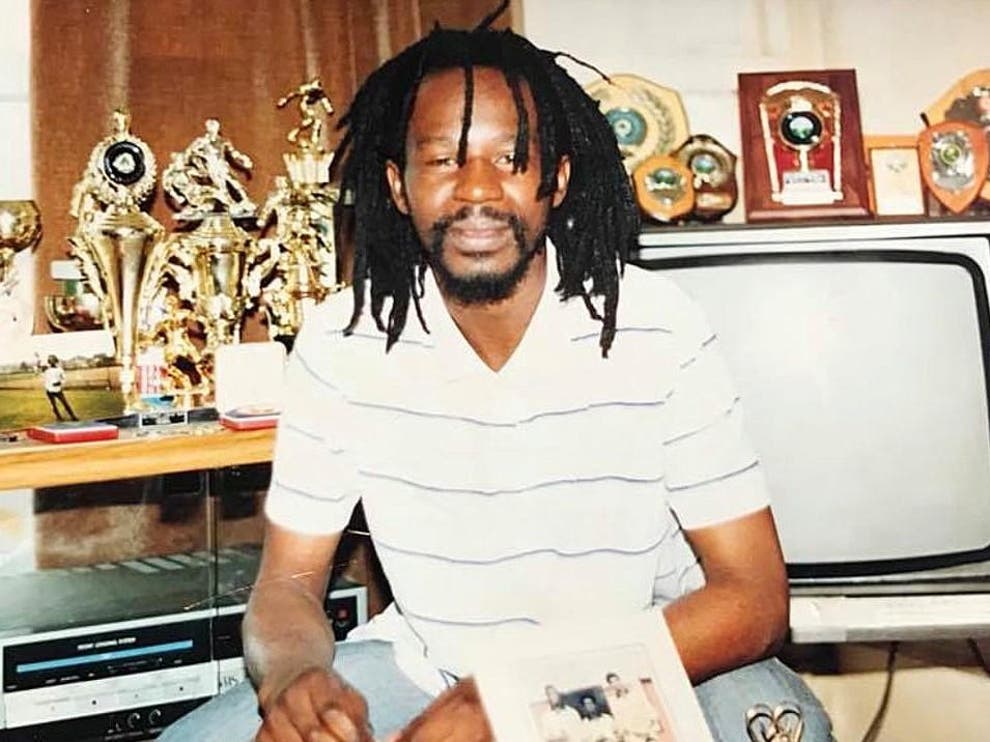

Errol Graham: Family of man who starved to death after benefits cut off lose High Court challenge against government

Relatives had accused Department for Work and Pensions of failing in ‘duty of care’ to grandfather of two

The family of Errol Graham, who starved to death in his flat in 2018 after his benefit payments were stopped, have lost their legal challenge against the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP).

A High Court judge ruled on Wednesday DWP officials did not break the law when they cut off Graham’s payments and also dismissed claims against the government’s safeguarding policy for ending benefits.

Graham weighed just four and a half stone (30kg) when bailiffs discovered his body after breaking into his Nottingham council flat to evict him.

The only food in the property at the time were two tins of fish, both of which were four years out of date.

His daughter-in-law Alison Turner said the 57-year-old had turned into “skin and bones” after his employment support allowance (ESA) benefits were stopped eight months earlier.

DWP officials terminated his payments after the grandfather of two did not show up for a meeting, despite knowing Graham had long struggled with mental health problems.

“He’d stopped going out or answering calls because he could no longer bring himself to deal with people – which is pretty much the number one classic sign of mental health deterioration,” the 31-year-old full-time mother-of-two told The Independent last year.

“Yet no one at the DWP bothered to red-flag that something serious may be wrong. There was no duty of care. He didn’t reply so he was crossed off their books.”

In a handwritten letter found in his flat after his death, Graham wrote of the devastating impact of his depression.

“I find it hard to leave the house on bad days. I don’t want to see anyone or talk to anyone. It’s not nice living this way,” he said in the letter, which was never sent.

“Being locked away in my flat I feel I don’t have to face anyone. At the same time, it drives me insane. I am a good person but overshadowed by depression.

“I dread any mail coming, frightened of what it might be because I don’t have the means to pay and this is very distressing. Most days I go to bed hungry and I feel I’m not even surviving how I should be.”

Ms Turner launched her High Court case against the DWP in January, arguing the benefits system was “not fit for purpose”.

During Graham’s inquest in 2019 it emerged standard government procedure was to stop benefits once a claimant had failed to respond to letters and calls or did not answer the door for two safeguarding visits.

Speaking at the time, assistant coroner Dr Elizabeth Didcock said that such a system meant that “the safety net that should surround vulnerable people like Errol in our society had holes within it”.

The DWP policy was updated after Mr Graham’s death to encourage officials to carry out a home visit before cutting off payments to anyone about whom there were “safeguarding concerns”.

But Ms Turner alleged in her legal claim both this policy and the specific decision to end her father-in-law’s benefits were unlawful.

Her lawyers argued the requirement for claimants to show “good cause” if they missed an appointment unfairly placed the onus of responsibility on beneficiaries, and that even the revised safeguarding policy did not compel officials to look into why claimants suffering from mental ill health might have ceased contact.

But Mr Justice Bourne ruled against both arguments, stating the “references in the policy to a burden of proof were lawful".

The judge said the need for benefits claimants to show "good cause" for missing an appointment was not "a materially misleading impression of the law” and he also ruled it was clear the DWP did have “due regard to the need to advance equality of opportunity between disabled and non-disabled people".

He also ruled Ms Turner had failed to show the government did not meet its own duty to inquire into Graham’s disappearance.

“The defendant’s officials were confronted with a complete cessation of contact by Mr Graham and an absence of any attempt by him to do anything to permit his ESA review to progress.

"Neither the legislation nor the defendant’s policy at the time mandated any further specific steps to be taken in that situation."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks