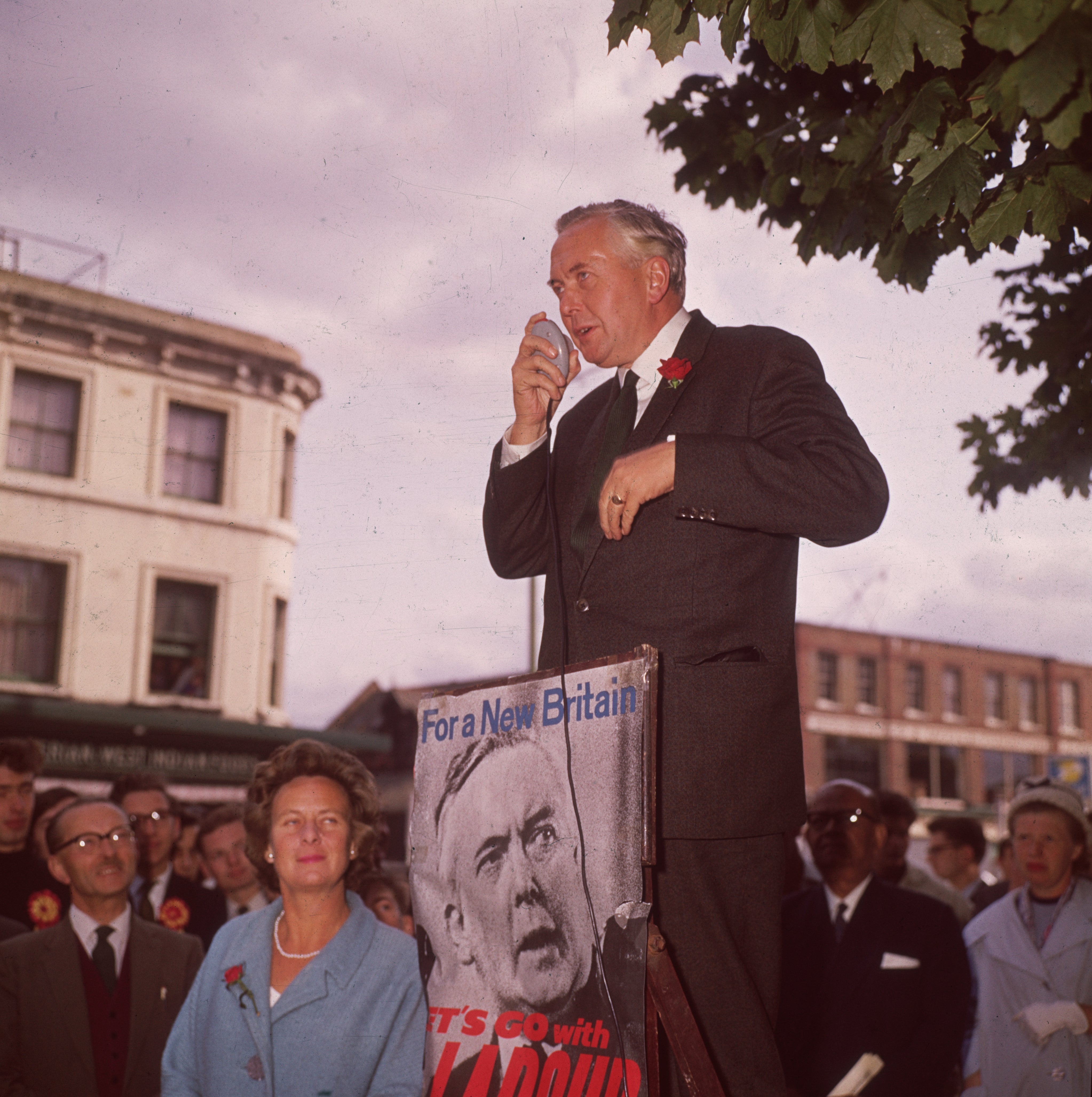

My uncle was Mary Wilson’s companion – Harold had affairs, yes, but she had her own secret life too…

When news broke this week that Harold Wilson’s closest aides had kept his affair with a colleague secret for 50 years, thoughts turned to his wife. But, says Rowan Pelling, those who knew her never found her long-suffering and she was quite different to the ‘mousy’ wife people thought her to be

There are many less glorious epitaphs than the simple yet sincere statement “she made him happier than he had ever been”. This is what the Labour peer Bernard Donoughue said this week of Janet Hewlett-Davies, who was Harold Wilson’s deputy press secretary during his second term as PM and, as we have all just learnt, his lover.

The affair was a closely guarded secret for half a decade until Hewlett-Davies’s boss at Downing Street, Joe Haines, revealed it this week.

Some may baulk at the idea of a woman in her thirties making an older man happy (Wilson was 22 years Hewlett-Davies’ senior), but I’m with Donoughue, who told me shortly after the story broke that he believed giving someone else happiness is “a human value and asset, not to be discounted as worthless”.

Of course, sympathy is often stretched when betrayal is involved. For all the fashionable talk of polyamory and hook-ups, we live at a time of heightened sensitivity around infidelity.

This is surely connected to soaring divorce rates and restless swiping for potential lovers on dating apps. But it’s important to remember the 1970s were a very different era: people married young and often stayed together for life.

In the context of that long commitment, couples were often more tolerant about marital wobbles – especially if great care was taken not to publicly humiliate their spouse.

When I talked to Donoughue, he was very much of that compassionate mindset, saying: “Nearly all my friends – male and female – have confessed that they’ve had this kind of aberration. If you’re married for a long time the path is very windy and rocky. There are good and bad moments. You may meet people who suit you for a time. Life is complex.”

His and Haines’ key concern was that the story of Wilson’s love affair should not be treated as wrong or scandalous, but as something that made sense within the context of the duo’s close working life and mutual obsession with politics.

Donoughue points out that Wilson was tired and dispirited at this point in time. This was partly a result of having become “entangled” with Marcia Williams, his political secretary (ennobled later to Baroness), who “behaved appallingly, hectoring and swearing at him”.

By contrast, he says Hewlett-Davies offered intelligence, warmth and comfort, as well as a close understanding of the PM’s political drivers. Wasn’t Wilson scared, I ask, that Williams would uncover his liaison? The peer says that that was another key reason for secrecy, as she would have “destroyed” her rival.

But what of Mary Wilson? This question particularly interests me because for many years (certainly throughout my teens and into my forties) my beloved uncle John – a lawyer who did a lot of work for the Church of England, as well as Peter Palumbo – was busy “walking” Mary to various social and cultural engagements.

I’m not beginning to suggest an affair: my uncle was in a same-sex relationship and 25 years younger than Mary. But they certainly found amusement in one another’s company and shared their Christian faith.

My uncle (still alive, but suffering from Alzheimer’s) was that wonderful kind of man who adored flirting and gossiping with everyone. He charmed straight women with his exuberant blend of wit, attention and intelligent conversation.

Mary and John’s friendship makes even greater sense in terms of Donoughue’s analysis of the Wilsons’ marriage. Mary, he points out, wasn’t interested in politics and absented herself from the daily churn of No 10.

She had been happiest when Harold was an Oxford don and her true passion was poetry, followed by the Scilly Isles. Poet John Betjeman was a huge influence and mentored her work, leading to several published volumes of verse.

Politician Roy Hattersley pointed out that Mary was a beady, engaged woman, nothing like the mousy wife of Private Eye’s lampoon, Mrs Wilson’s Diary, and my uncle said the same.

Once you understand this, it’s easy to comprehend that the astute, sympathique Hewlett-Davies was in many ways Wilson’s “political wife”, as Donoughue puts it. The duo had an intimacy born of shared convictions.

He also says he believes Harold wasn’t fulfilled at that period in “his personal life”, which suggests the Wilsons’ marriage had ceased to be physically intimate – but Donoughue is far too discreet to expand on the topic.

But many who are themselves in a long-lived relationship (yes, I’m sticking my hand up after 29 years of married life) will relate strongly to this interpretation of what happened.

Donoughue is clearly protective of what he views as a real love story for both parties – not wanting it tainted by tut-tutting moralisers

I freely admit I have felt so close to two colleagues over my time editing magazines (one in the 1990s and another more recently) that I openly referred to both men as my “work husband”.

While neither scenario developed into love affairs, I often reflect that’s partly because I was lucky to have an existing satisfactory love life. And, yes, my husband was aware of the closeness I felt to those workmates and unruffled by it, having enjoyed similar relationships in his own journalistic life.

Of course, more feathers are ruffled, as well as hearts broken and dignity dashed, when tendresses evolve into fully fledged love affairs. That’s why most sensible people who err within long relationships don’t broadcast the fact.

What some see as duplicitous and cowardly behaviour may in fact be more motivated by genuine horror of hurting those you love. I should make it crystal clear I’m not talking about that brand of perpetual deceiver who feels entitled to philander at will, no matter the consequences – in the vein of one more recent PM.

This is why Donoughue and Haines went to such great lengths to keep Wilson’s love affair a secret – until the deaths of all parties, lovers and their respective spouses (Hewlett-Davies was the last to die, in October last year) meant no one would be adversely affected by the tidings.

As I told Donoughue, I find it an incredibly touching story. The modern breed of special adviser, we both agree, would be running off to sell their carefully hoarded “confidences” to the highest bidder as soon as they were out of office.

And Donoughue is clearly protective of what he views as a real love story for both parties – not wanting it tainted by tut-tutting moralisers. We agree that the Great British vice is hypocrisy: do what I say, not what I do. Perhaps this is because of the rise of impossibly high relationship expectations.

I’ve long remembered that in the early Noughties, my publican mother showed me an entry from her Pears’ Cyclopaedia for 1971 that stated 70 per cent of the UK’s married couples did not believe adultery should axiomatically lead to divorce.

She mused that 30 years later it was likely the figures would be reversed, since the rise of romantic love as a creed had supplanted the notion of Christian forgiveness.

My mother was very loyal to my much-married father, yet took tender care of several middle-aged couples amongst her regular drinkers she intuited were lovers, rather than husband and wife.

She was particularly fond of one pair who came in on a weekly basis, known as “the Wednesday couple” for their preferred day of lunching. We knew this duo for almost 20 years and then they disappeared.

Later, mum received a beautiful letter from the man telling her of his love’s death, explaining the affair and the fact they had never wanted to end one another’s marriages. It was a very British, understated attachment with consideration for both families. The letter made my mother cry.

But then as Donoughue says, these things are complex. In Joe Haines’ memoir, he said that Marcia Williams once told Mary Wilson: “I slept with your husband six times and it wasn’t very satisfactory.”

Donoughue doesn’t dispute this account, but notes whatever happened was back in the 1950s and wasn’t a love affair so much as something that gave Williams her lifelong hold over Wilson.

What is certain is that Mary Wilson didn’t hold anything against Williams. The two women were often seen lunching either side of Harold in the House of Lords after his premiership.

After Wilson’s death in 1995, the pair carried on their habit of weekly lunching – also on Wednesdays, as it happens. Mary said of Marcia: “She was a real politician, I wasn’t. She knew all the ropes.”

We must also hope our confidantes are as loyal and kind as Donoughue, who deserves the last word on the matter: “I wanted [Wilson] to be treated humanely. This was a human being at the end of a long and battering career. Finally, he met Janet who he knew he could trust, treated him really well – and really loved him.” Amen to that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks