From Brexit to Trump and Covid, how The Independent has covered the biggest stories

In March 2016, The Independent went digital-only – and it has been a time filled with extraordinary and important events. Here’s how we’ve covered some of the biggest moments

Five years ago, when The Independent became digital-only, Britain was on the verge of a seismic political event. The country voted to leave the EU and followed included conflicts and clashes that have split the nation and torn political parties apart, huge marches for another vote, and more deadlines and crunch talks than any of us would care to remember. There remain consequences to be fully realised (though not yet the promised £350m a week for the NHS, some would point out).

Now, in 2021, we stand in the middle of a pandemic that has cost countless lives around the world and touched every one of us. Some aspects of life will never be the same, whether through grief and loss or ill health, or perhaps the economic turmoil that has ensued.

Events may seem to have greater importance the closer we are to them, but even so it doesn’t seem unfair to suggest that these last five years have been notable than most. On top of Brexit and the pandemic, we have seen three prime ministers, the rise and fall of Donald Trump, and the end of Isis in the Middle East. War has continued to rage in Syria and Yemen. And through it all, the urgency of the climate crisis has only grown.

And it is in the challenge of covering these five years that The Independent has been able to reach more readers than ever before. Since our final print edition left the presses in March 2016, our website has gone from strength to strength, with more and more people looking for a truly independent outlook to help them make sense of the world. We have seen global monthly readers top 100 million, while subscribers have turned to the Daily Edition and Independent Premium.

Here are some of our reports from those extraordinary moments, as they were filed by our team of correspondents and commentators in Britain, the US and around the world.

June 2016: The results came in and Britain had voted to Leave. So what went wrong for the Remainers?

If ever there was a cause that had heavyweight opinion behind it, it was the Remain campaign. Voices of authority from all over the world piled in to warn the British public against the perils of Brexit – though there was less said about the good that might come from staying in the EU.

It was Project Fear once again. That was the name given two years ago to the campaign to persuade Scotland not to leave the UK, which included a warning from George Osborne, reinforced by Ed Balls for Labour and Danny Alexander for the Lib Dems, that the Scots could not count on a deal on currency union if they opted for independence. That was mild compared with the weeping and gnashing of teeth that would be the consequences of Brexit, according to the warnings from a veritable galaxy of the great and the good.

July 2016: David Cameron had gone and fresh from their Vote Leave triumph, Boris Johnson and Michael Gove were set to run on a joint ticket – until Gove had other ideas, just before Johnson’s big announcement speech

Boris Johnson was still wearing his red tie when he bumbled up to the lectern. Vote Leave chose red to make people think of Labour. They were the votes they needed above all else. British Tommies wore it for morale. To hide the blood.

“This is a time not to fight against the tide of history but to take that tide at the flood and sail on to fortune,” he said. The first and the last drafts of history will all recall that it was through these words of Brutus, the uncrowned emperor of political assassins, that he revealed his mortal wound.

Equally, it served as a gentle reminder that Boris is working on a biography of Shakespeare with a £500,000 advance, and it was kind of him to reassure his shell shocked audience and the wider world: don’t cry for me, I’ll be all right.

Holly Baxter: When you cross-reference Theresa May's speech with her voting record, it's as if she didn't mean anything she said

July 2016: As she took office in No 10, Theresa May made her “burning injustices” speech about all the wrongs she was ready to right for Britain. But had she backed it up?

It’s great news that Theresa May is our new Prime Minister, isn’t it? I for one felt really warm and fuzzy inside when she made her speech all about being the servant of working people, the protector of struggling young people, the defender of the employee against asset-stripping companies and big business meanies, and the champion of social mobility.

When she said, “it is apparent to anybody who is in touch with the real world that people do not feel our economy works [for everyone]” because it was “ordinary members of the public” who “made real sacrifices after the financial crash in 2008”, I completely forgot that, on 4 September 2013, she voted against calling on the government to get more people into work, against introducing a compulsory jobs guarantee, against standing up for families in the private rental sector, against curbing payday lenders, and against banking reforms.

Rupert Cornwell: Donald Trump's inauguration was full of promises but no clear plan to heal America's wounds

January 2017: He’d seen off Hillary Clinton and pledged to drain the swamp. But what did America’s 45th president have in store for the next four years as he took office?

He fought the campaign as a populist – and today from the most solemn stage, in his first defining speech as President, Donald Trump delivered a populist manifesto to his country. He would make America great again, and nothing a self-serving national elite or an ungrateful world would do would stand in his way.

“I, Donald John Trump, do solemnly swear to faithfully execute...” At exactly noon on Friday, the words that were virtually unimaginable even four months ago, wafted out over a rainy Washington and the world. And with them his country entered a new and uncertain future.

In the setting where Abraham Lincoln, Franklin D Roosevelt and John F Kennedy had taken the oath of office, a property mogul and reality TV virtuoso became the 45th President of the United States, and one unlike any other: without the slightest experience of public office, richer than any of his predecessors, the most unpredictable and surely the most divisive.

And he delivered a speech unlike any other: terse and blunt, and shorn of the soaring and cheering rhetoric that have marked every other inaugural address. There was little overt emphasis of unity, no evocation of a shining city on a hill, as per Ronald Reagan, no talk of an America as noble example for the rest of the planet. Mr Trump instead vowed to remake a country he portrayed as battered and dispirited, riven by violence, and neglected by a pampered establishment.

Harriet Agerholm: ‘I don’t have a home, so I come here’ – The school providing sanctuary to Grenfell survivors

July 2018: The blaze at Grenfell Tower in West London in July 2017 killed 72, injured more than 70 and raised a litany of questions about the safety of high-rise blocks. The Independent followed the plight of those who escaped not just in the immediate aftermath but also one year on, as the youngest among them still struggled to comprehend the tragedy

A year after the blaze at Grenfell Tower, nine-year-old Safiya El-Hafedi keeps having dreams about fire. In one of her most recent, there were imaginary flames in her house. “Then my family all died and I was flying up to the sky,” she says. “And I saw my friend that died in Grenfell and my cousin Mehdi. Then it stopped, for some reason. That’s all I remember.”

Safiya is sitting in her deputy headteacher’s office at Thomas Jones Primary School, five minutes walk from the plastic-wrapped shell of the highrise. Five members of her family, the El-Wahabis, died in the early hours of 14 June 2017. Safiya’s cousins Mehdi, aged eight, Yasin, 20, and Nur Huda, 16, were killed in their 21st-floor flat along with their parents, Abdulaziz, 52, and Faouzia, 41.

Several children at the school have been directly affected by the inferno, which resulted in 72 deaths. Some had friends or relatives in the tower and watched the flames spread up the 24-storey building. Three children lived in the tower and were forced to flee.

Hafsa Khalloud, aged 11, describes how her mother received a phone call from a friend in a neighbouring building on the night of the blaze. “Get out,” she told her. The fire was two storeys below their flat. “My mum got my dad up, then my dad held my little sister and my brother woke up. I put on some slippers,” says Hafsa.

Jonathan Liew: In the end it didn’t matter that football didn’t come home, what mattered was the scintillating, month-long feeling that it might

July 2018: In the semi-final against Croatia, England’s dream of winning the World Cup in Russia was ended. But for a few fleeting seconds, or perhaps even days and weeks, it had felt like they really might have done it

And with a rumble and a roar and a laser-guided swing of Mario Mandzukic’s boot, it was all over. The World Cup that England had earmarked as football’s homecoming ended crouched on their haunches, their shapes denting the Luzhniki turf. Party over. Lights on. Everybody out. England are coming home, but football – alas – looks like it will be staying in the taxi and going on somewhere else.

England vs Croatia in the World Cup semi-final was a game that everyone will have watched, but no two people will have seen in the same way. The gazes are too numerous, the stakes too high, the emotions too deep. Every instant was splintered into a million different interpretations the moment it occurred, like light refracting or glass shattering. Perhaps when Ivan Perisic turned the ball in for Croatia’s equaliser you saw an astonishing feat of athleticism and agility. Or perhaps you saw a clear foul for a high foot.

Perhaps when Mandzukic turned in Croatia’s winning goal you saw a sumptuous flicked header, an outstanding finish under pressure. Or perhaps you simply saw the darkness stretching out in front of you, the loneliness, the desolation, the void. Four years, eight years, 52 years, who cares? In any case, it will be a long time until either England or the English are on the crest of a wave like this again, and in the meantime we’ve all got work in the morning on a raging hangover.

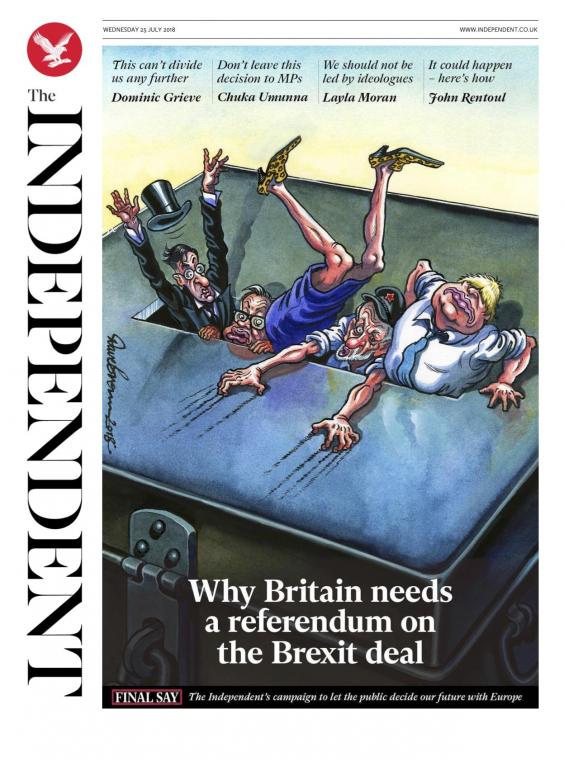

August 2018: More than two years after the referendum, it felt like the Brexit that Britain was facing was not the one that had been promised. This was the start of our campaign for a second referendum, which led to a petition signed by a million people, as well as marches on parliament demanding a Final Say

The Independent today launches a campaign to win for the British people the right to a final say on Brexit. Come what may in the months ahead, we maintain our commitment to our readers to retain balance and present many different points of view. But on this subject we believe a referendum on the final deal is right.

March 2019: The caliphate was declared defeated – no more territory belonged to Isis in Iraq and Syria. But Robert Fisk warned that was not the end of the group

After all the headlines about the supposed defeat of Isis, anyone who doesn’t believe a word of it may seem a bit of a spoilsport. But whenever I read that victory has been declared – whether it be of the Bush “mission accomplished” variety or the “last Isis stronghold about to fall” fantasy – I draw in my breath. Because you can make a safe bet that it’s not true.

Not just because the fighting around Baghouz is, in fact, still continuing outside the wrecked town. But because there are plenty of Isis fighters still under arms and ready to fight in the Syrian province of Idlib, along with their Hayat Tahrir al Sham, al-Nusra and al-Qaeda comrades – almost surrounded by Syrian government troops but with a narrow corridor in which they could escape to Turkey; always supposing that Sultan Erdogan will let them. There are Russian troop outposts inside these Islamist front lines, along with Turkish military forces but the tentative ceasefire which held for five months has become a lot more tenuous in the past few weeks.

Harriet Hall: When she allowed her emotion to show during her resignation speech, Theresa May finally did something good for women

May 2019: In the end, the fight for a Brexit deal ended Theresa May’s premiership. She signed off with a speech outside No 10 during which her voice cracked with emotion for “the country I love”

In the moment when Theresa May allowed her emotion to show while signing off her resignation announcement this morning, she did more for women than she has over her entire political career.

Hearing her voice crack when she said running the country she loves has been “the honour of my life”, it was difficult not to feel sad about the fact that another woman’s time at the helm of the country was over – not to mention the fact that her tumultuous time in office will inevitably be used against other women in politics in the future.

John Rentoul: How does Boris Johnson solve Brexit now?

July 2019: His moment was finally here – how would (or could) Boris Johnson tackle his Brexit conundrum as he took stepped into Downing Street?

Does Boris Johnson have a plan to get Britain out of the EU? If he does, it is likely to fail, which would mean that on 1 November we will still be in the EU and our new prime minister may well be announcing a general election – saying parliament has blocked him and he needs a new mandate to finish the job.

That seems the most likely outcome to me, but let us go through the Johnson government’s Brexit challenge step by step to test our assumptions and to see what other paths history might follow.

January 2020: As Britain finally took its leave of the European bloc, could there be hope of a re-entry?

British re-entry, which we might dub “Bre-entry”, will not replace Brexit as a national obsession for some time, if ever.

Still, the European issue is not going to go away, and the debate about Britain’s relationship with the rest of the continent is not going to suddenly disappear entirely. It has been around in its current form since the end of the Second World War, and in other iterations for many centuries before that, all the way past Hitler, the Kaiser, Napoleon, the Spanish Armada, Henry VIII’s break with Rome, the Norman Conquest, the Anglo Saxons, Viking incursions all the way back to the Romans. As Boris Johnson once said, Brexit does not mean Britain is about to be towed out into the Atlantic (much as some might like it).

In fact there are perfectly plausible cases to be made for Bre-entry being inevitable; and for it being inconceivable.

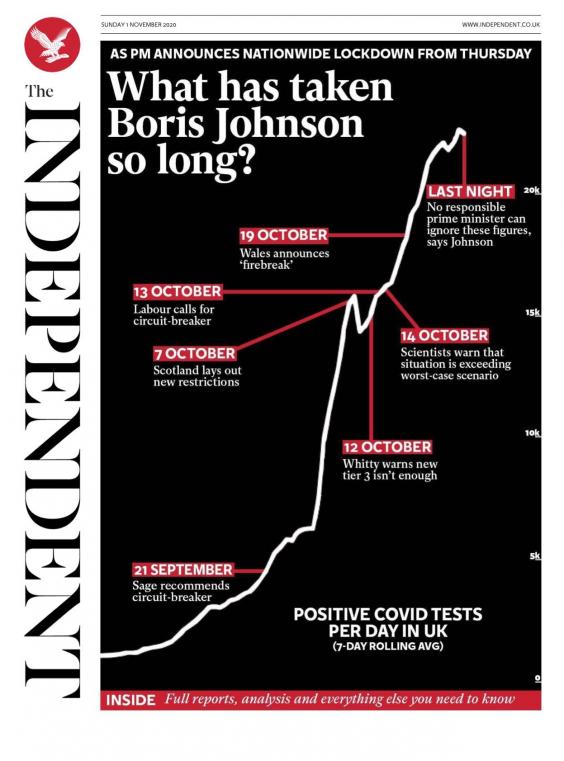

March 2020: We’ve now grown weary of the wooden panels of that Downing Street briefing room, the talk of lockdown, social distancing and protecting the NHS. But this time last year, as Britain contended with the impending emergency, Boris Johnson made his first seismic televised address

On Monday afternoon, at a press conference in Downing Street, prime minister Boris Johnson announced some of the most draconian measures in this country’s history. Well, apparently he did anyway, as that’s what everyone keeps saying, but I’ve watched it back twice now and I’m not sure I can actually find any.

Have restaurants, pubs, theatres and nightclubs been ordered to close, as in France, Spain, Belgium, Austria, New York, and almost everywhere else? No, they haven’t. Have people been asked not to go to them? Yes, they have, kind of. Not told, just asked.

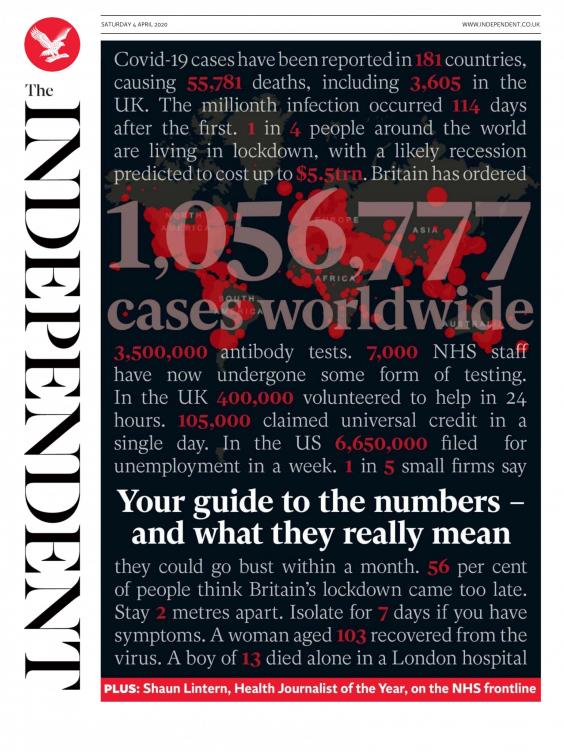

Andrew Buncombe: From Wuhan to the rest of the world

April 2020: It had started quietly, with reports of a new disease isolated to one Chinese city. Within four or five months Covid had crossed the globe, as we marked one million cases worldwide

How did it happen? And how did it happen at such speed? How could what appeared to be a few cases of a new strain of flu in China – and with even that news largely being lost amid religious festivities and new year celebrations – spread and snap the world shut?

While there are nations where its vice-like hold has been most life-transforming and deadly – China, Italy, Iran, Spain, and now the US – perhaps without exception, nowhere has escaped its impact.

For many of us, the first reported cases and deaths felt far away and literally foreign. Now, as the global number of confirmed infections (collated by Johns Hopkins University) passes one million, they are close to hand and among us. We know of people who have died, or else been taken sick. Lots of us have most likely already been infected, but without testing we cannot be certain.

Andrew Buncombe: I was arrested, jailed and assaulted by a guard. My ‘crime’? Being a journalist in Trump’s America

July 2020: Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis brought old questions about American policing to the fore again. This is our own Chief US Correspondent’s story

In the van, the woman insisted on lying lengthways in the compartment she was in. I was squeezed into a tiny, claustrophobic section, perched on a narrow bench, trying not to slip off as the van sped through the city’s boarded-up downtown, towards the jail. By this point, the so-called “belly chain” had become so tight I could not fully exhale. It felt obscene and preposterous to have to inform the officers I could not properly breathe, that phrase having become weighted with such power and resonance during the Black Lives Matter movement, echoing the gut-wrenching final words of George Floyd. But that was the situation. I could not properly breathe. One of the officers responded: “If you can speak, you can breathe.”

Bel Trew, Oliver Carroll, Samira el-Azar, Richard Hall: The seven years of neglect, and 13 minutes of chaos, that destroyed Beirut

August 2020: Without warning, a huge explosion ripped through Lebanon’s capital, killing hundreds. What had caused the blast? Years of mismanagement, neglect and corruption

Residents across central Beirut were peering quizzically at a mushroom cloud of grey above their heads when the sky cracked open and a tidal wave of pressure roared through.

It was like sound itself had imploded in everyone’s ears. The world simultaneously broke apart and snapped shut. Bodies were pulled into the air and thrown across rooms and streets. The facades of apartment blocks, offices and hospitals were peeled off and chewed into pieces.

The explosion unleashed warring tornadoes of pressure that wrestled everything off the walls and the floors, spitting shrapnel that cut through the air like bullets. The power of the blast instantly eviscerated windows, smacked down buildings, crumpled steel shutters and crushed cars like a giant’s fist.

“It was like an atomic bomb,” says Hala Okeili, 33, a yoga instructor who was less than a mile away from the port when disaster struck. “I thought they had started a war and someone was bombing us.”

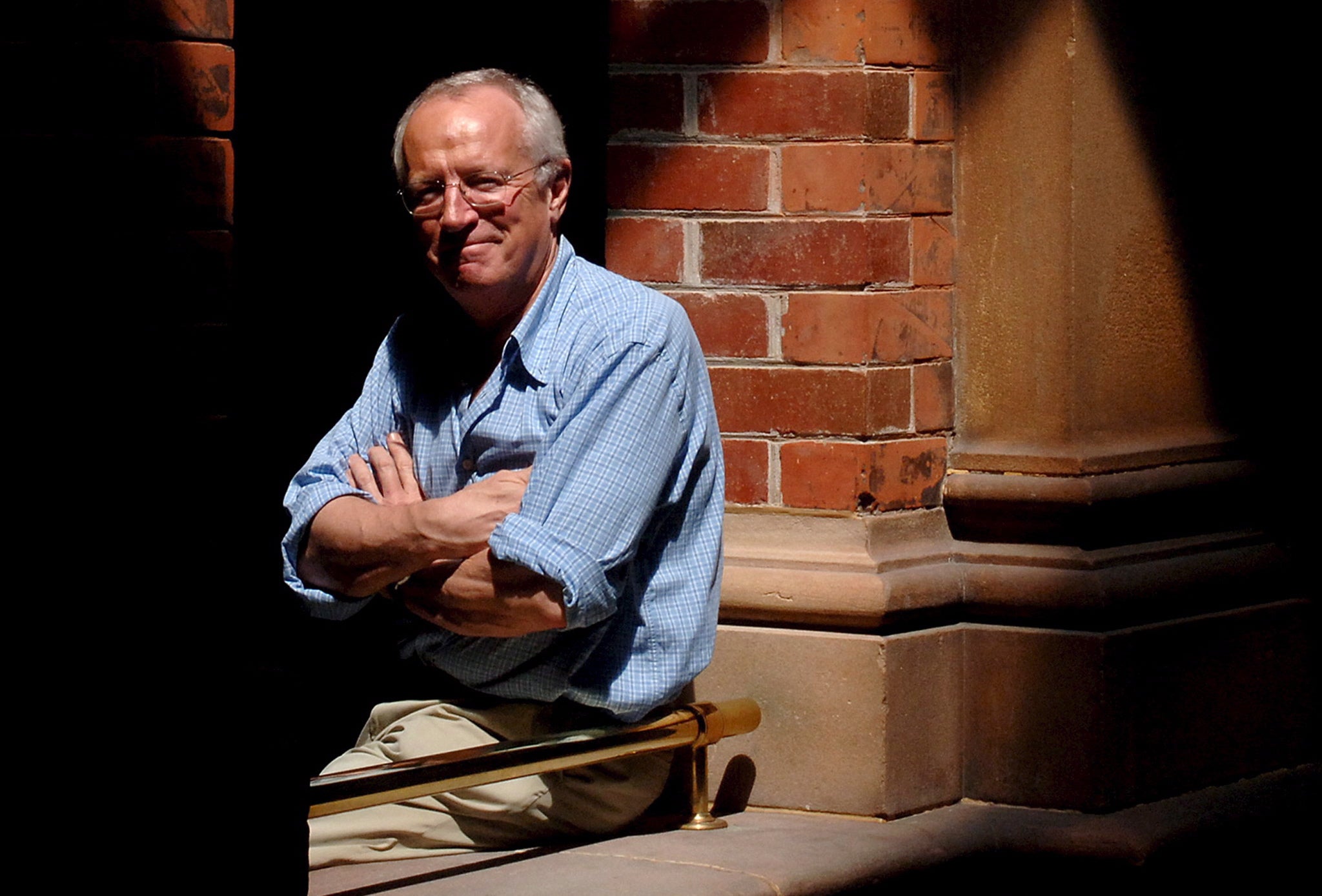

Patrick Cockburn: Robert Fisk wasn’t only a magnificent journalist, but a ‘historian of the present’ who illuminated the world

November 2020: After the passing of The Independent’s distinguished foreign correspondent, his friend and longtime colleague Patrick Cockburn wrote this tribute

I first met Robert in Belfast in 1972 at the height of the Troubles when he was the correspondent for The Times and I was writing a PhD on Irish history at Queen’s University.

I was also taking my first tentative steps as a journalist, while he was swiftly establishing a reputation as a meticulous and highly-informed reporter, one who responded sceptically – and rigorously investigated - the partisan claims of all parties, be they gunmen, army officers or government officials.

Our careers moved in parallel directions because we were interested in the same sort of stories. We both went to Beirut in the mid-1970s to write about the Lebanese Civil War and the Israeli invasions. We often reported the same grim events, such as the Sabra and Shatila massacre of Palestinians by Israeli-backed Christian militiamen in 1982, but we did not usually travel together because, aside from the fact that Robert usually liked to work alone, we wrote for competing newspapers.

When we did travel together during the wars, I was always impressed by Robert’s willingness to take risks, but to do so without bravado, making sure we had the right driver and the car had petrol that had not been watered down. One reason he had so many journalistic scoops - such as finding out about the massacre of 20,000 people in Hama by Hafez al-Assad in Syria in 1982 - was that he was an untiring traveller. One friend recalls that: “He was the only person I’ll ever know who could, almost effortlessly, make up limericks about the south Lebanese villages, while he was driving through them.”

November 2020: Three days after the polls closed, America was on the cusp of the announcement of Joe Biden as the president-elect. As the Trump campaign scrambled to contest the result, Rudy Giuliani called a bizarre press conference in a Philadelphia landscape firm’s car park

It began, as all good 2020 capers do, with a tweet from the president of the United States. It ended with his personal lawyer in the parking lot of a landscaping company, struggling to be heard over a man in his underpants shouting about George Soros.

They say a star burns brightest just before it dies, and this was the Trump presidency in all its flaming glory.

For five straight days, the world had waited for news, any news, from Pennsylvania, which for all of that time had been expected to imminently decide the winner of a bitter election. The president had spent much of the intervening period making grave and entirely unsubstantiated allegations of voter fraud, but even so he was unusually quiet.

Mary Dejevsky: The next generation won’t see leaving the EU as we do

January 2021: The transition was over, Britain was on its own. But what will those who didn’t have their say in 2016 make of it all?

As with Ursula von der Leyen quoting TS Eliot, so in the UK parliament. When Brexit was finally completed, with the signing of the Christmas Eve agreement between the UK and Brussels and then its passage into UK law via the EU (Future Relationship) Act, there was both an end and a beginning.

After almost half a century as a member of what was to become the European Union, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland enters 2021 as – in the words of Boris Johnson – “an independent coastal state”.

The final departure, it has to be said, was something of an anticlimax. For all the prime minister’s efforts to wrap his every appearance in many national flags, there was little sense of either the signing ceremony for the Trade and Cooperation Agreement or the 30 December parliamentary debates being great national moments.

Andrew Buncombe: Washington DC is a city of sounds as Joe Biden inaugurated and ‘democracy prevails’

January 2021: The reign of Donald Trump was over, and Joe Biden was set to take the oath and step into the Oval Office

On Inauguration Day, Washington DC was a city of sounds. There was the sound of Donald Trump leaving the White House for the final time, clattering over the city in Marine One, his helicopter taking a circuitous, look-at-the-sights-as-we-leave route. There was the sound of his final boasts, as he spoke at Joint Base Andrews about his administration’s purported accomplishments.

There was the richness of music and melody, of Lady Gaga and Jennifer Lopez performing on a day like no other. There were the notes of both optimism and clear-eyed reality in the poetry of Amanda Gorman, the 22-year-old strikingly honest about the nation’s inequality, yet suggesting “there is always light, only if we are brave enough to see it”.

Then there was the gruff familiarity of Joe Biden, solemn and serious, still taking in the occasion and everything that had carried him to this moment, as he was sworn in as the US’s 46th president by Chief Justice John Roberts, noting that to “secure the future, America requires so much more than words, it requires the most elusive all things in a democracy: unity”.

Yet, if there was one sound most frequently heard on Wednesday as Mr Biden took the oath of office at the age of 78, it was that of a sigh of relief.

February 2021: With Cop26 in Glasgow around the corner, we looked at where the world stood in its fight to limit global warning

The world entered 2021 faced with an alarming set of statistics. The six hottest years on record have all occurred since 2015, and 2021 is expected to continue the run. The last 14 years have seen the 14 lowest Arctic sea ice levels since satellite records began. CO2 levels in the atmosphere are currently around 415 parts per million (ppm), and are expected to breach a level that is 50 per cent higher than before the industrial era later this year.

“It’s iconic because it shows how much we have actually altered the composition of the atmosphere through human action,” Prof Richard Betts, who leads the Met Office’s annual CO2 forecast, told The Independent as the news broke.

Mean global temperatures are now around 1.2C above pre-industrial levels. The path to limiting global warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, the aspirational target set by countries under the historic Paris Agreement, grows steeper year by year. But there are glimmers of hope.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks