What the Philby files tell us about the establishment that protected the Cambridge spies

As new documents reveal fascinating new details about the infamous MI6 double agent Kim Philby and his betrayals, Mark Hollingsworth reflects on how, despite the evidence, Philby and fellow Soviet agent Anthony Blunt were never truly brought to justice

In 1962, a tip-off by a KGB defector resulted in MI5 bugging the flat of John Vassall, an admiralty clerk who had access to sensitive state secrets while based in the British embassy in Moscow. Vassall was placed under intense surveillance, and a search of his flat in Dolphin Square, near parliament, revealed two cameras and exposed film concealed in a hidden compartment.

Vassall was arrested the same day. Panting with fear, he confessed to leaking secrets to the KGB. An exuberant Sir Roger Hollis, then head of MI5, rushed over to No 10 and gleefully told Harold Macmillan, the prime minister at the time, that the spy had been captured. “I’ve got this fellow Vassall... I’ve got him!” he said, with rare excitement in his voice. But the prime minister was not happy.

“I am not at all pleased,” he replied in exasperation. “When my gamekeeper shoots a fox, he doesn’t go and hang it up outside the Master of Foxhounds’ drawing room. He buries it out of sight. You just can’t shoot a spy as you did during the war. Better to discover him, then control him, but never catch him ... There will be a terrible row in the press, a debate in the House of Commons and the government will probably fall. Why the devil did you catch him?”

But it was too late. Vassall had confessed his guilt; he was convicted under the Official Secrets Act and jailed for 18 years.

Macmillan’s patrician disdain and lofty complacency regarding the infiltration of the British state by Soviet intelligence agents is reflected in the 21 MI5 files that have just been declassified by the National Archives. The documents reveal fascinating new details about the infamous MI6 double agent Kim Philby and his betrayals.

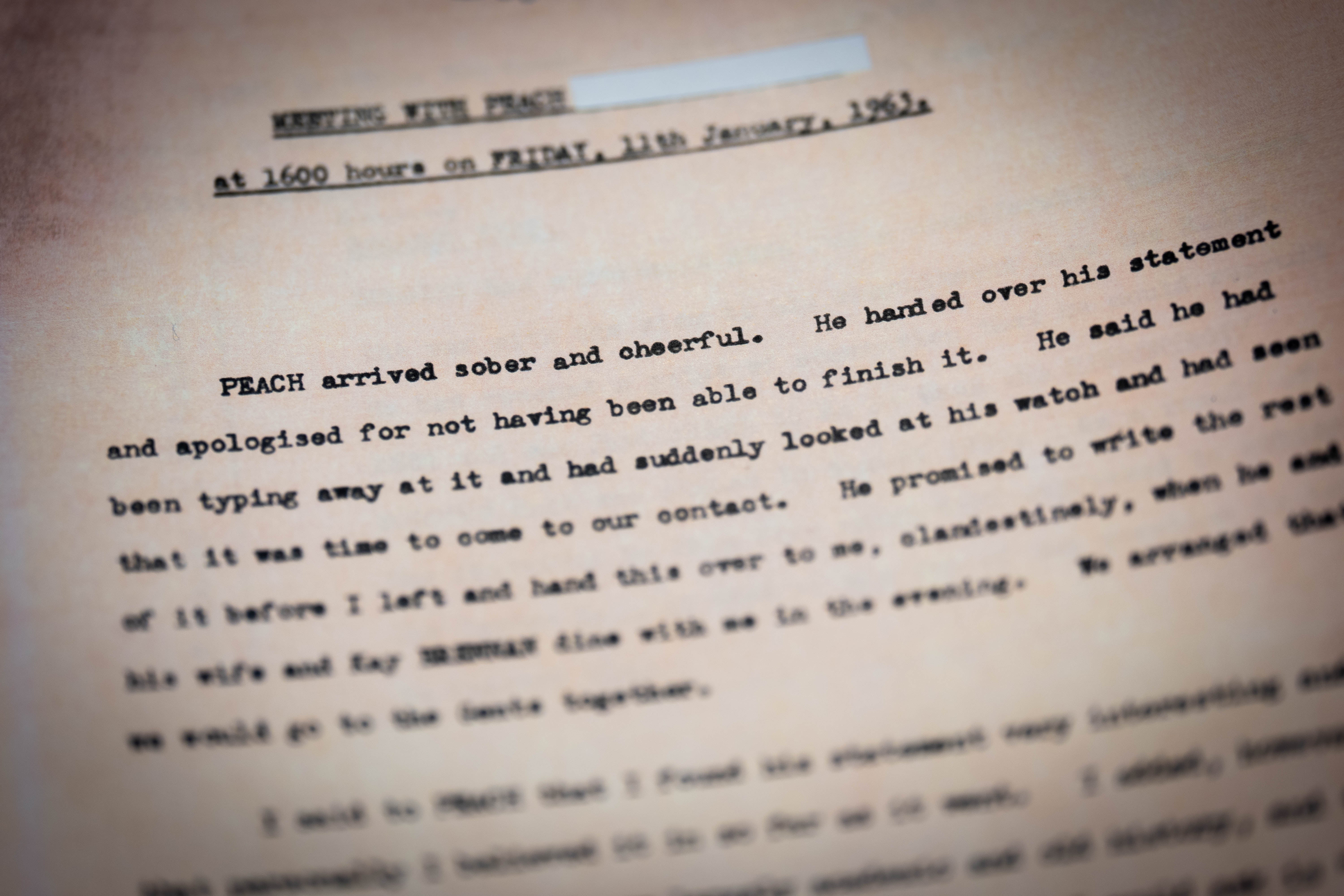

The most dramatic is a transcript of a conversation in 1963 in Beirut between Philby and his best friend Nicholas Elliott, who had been tasked to persuade his fellow MI6 officer to confess to being a Soviet agent.

Philby confessed he had betrayed Konstantin Volkov, a KGB officer who tried to defect to the West by offering details of nine Soviet moles inside MI6 and the Foreign Office. His information was priceless and would have changed the course of the Cold War. But his secrets would have led to Philby being unmasked as a Soviet spy, and so the MI6 officer tipped off the KGB. As a result, Volkov and his family were kidnapped in Turkey, drugged, placed in bandages on stretchers, and taken back to Moscow where they were executed.

When Philby was asked about the many people he had betrayed to the Soviet Union, his response was a masterclass in sophistry. “I can remember nothing specifically,” he replied. In fact, hundreds of British agents operating in communist bloc countries and risking their lives, notably in Albania in 1949, were captured and murdered after Philby tipped off his KGB controllers.

When asked about his relationship with the KGB, Philby claimed he had stopped working for the Soviet security agency in 1946 – a blatant lie. And he said he had had little contact with fellow Soviet agent Donald Maclean since 1934 – another lie. By the time of the meeting, MI6 already had evidence of Philby’s guilt after a former friend disclosed how he had tried to recruit her in 1934.

But shockingly, Elliott, his best friend and fellow MI6 officer, offered him a deal – immunity from prosecution in return for a full confession. Philby regarded the offer as a choice “between suicide and prosecution” and declined. A few days later he fled to Moscow, and some historians believe he was allowed to escape to avoid an embarrassing prosecution, in accordance with Macmillan’s view that it was better “to control a spy but never catch him”.

Philby’s fellow Soviet agent Anthony Blunt, surveyor of the Queen’s pictures, also received favourable treatment. He had betrayed his country since the 1930s, but the declassified files reveal how he confessed in his flat above the Courtauld Institute in 1964.

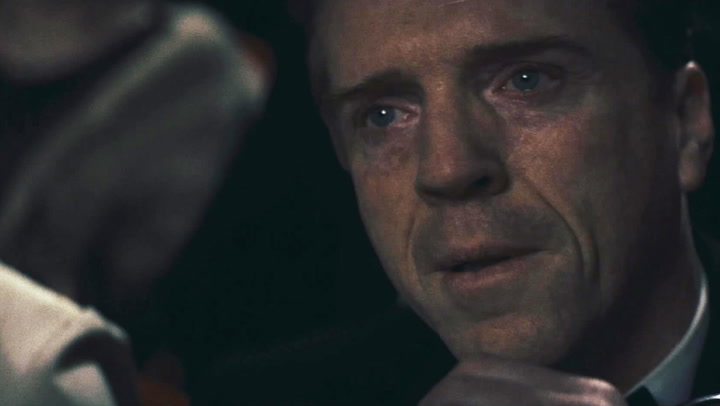

Under interrogation by MI5, at first Blunt denied everything as “pure fantasy”. But when offered immunity from prosecution, suddenly he changed his story. After a period of silence, he replied: “Give me five minutes while I wrestle with my conscience.”

As Blunt’s confession unfolded, his nervousness intensified with his right cheek twitching constantly. The secrets and betrayals poured out of the art historian as he revealed his secret schemes with the Cambridge spies to betray his country. However, he was never prosecuted, was later knighted, and amazingly, he was allowed to continue his responsibility for care and maintenance of the royal collection of pictures owned by the sovereign, based at Buckingham Palace – a decision that was premised on the vague and dubious notion that the “greater public interest is in no change becoming apparent”.

But perhaps the most shocking revelation in the newly released files is that the Queen was not told for almost 10 years that Blunt had confessed to being a Soviet double agent.

“[The Queen] took it all very calmly and without surprise,” reported her private secretary Martin Charteris. “She remembered he had been under suspicion in the aftermath of the Burgess/Maclean case.” It was not until 1979 that Blunt was unmasked in parliament by Margaret Thatcher, but only after a historian uncovered his treachery and planned to publish the details.

What emerges from the new files is the way that the secret state operated to a double standard. While their professed allegiance was to liberty and democracy, the documents show that the loyalty of MI6 officers was to their own agency, fellow officers, and the crown, but certainly not to the rule of law or to parliament.

The disease that infected Philby and Blunt could have been detected and diagnosed when they were first recruited by the KGB. But recruitment in those days was based on friendship and social class. “The Secret [Intelligence] Service resembled more an exclusive club, to all intents a band of brothers,” recalled former MI6 officer Philip Johns.

“Its members are recruited by invitation from an existing member. The background of a great many was Eton and Balliol, Sandhurst and Dartmouth. Funds voted for secret operations by parliament were employed under conditions not open to scrutiny, and the methods and practices were not accountable to any independent government department.”

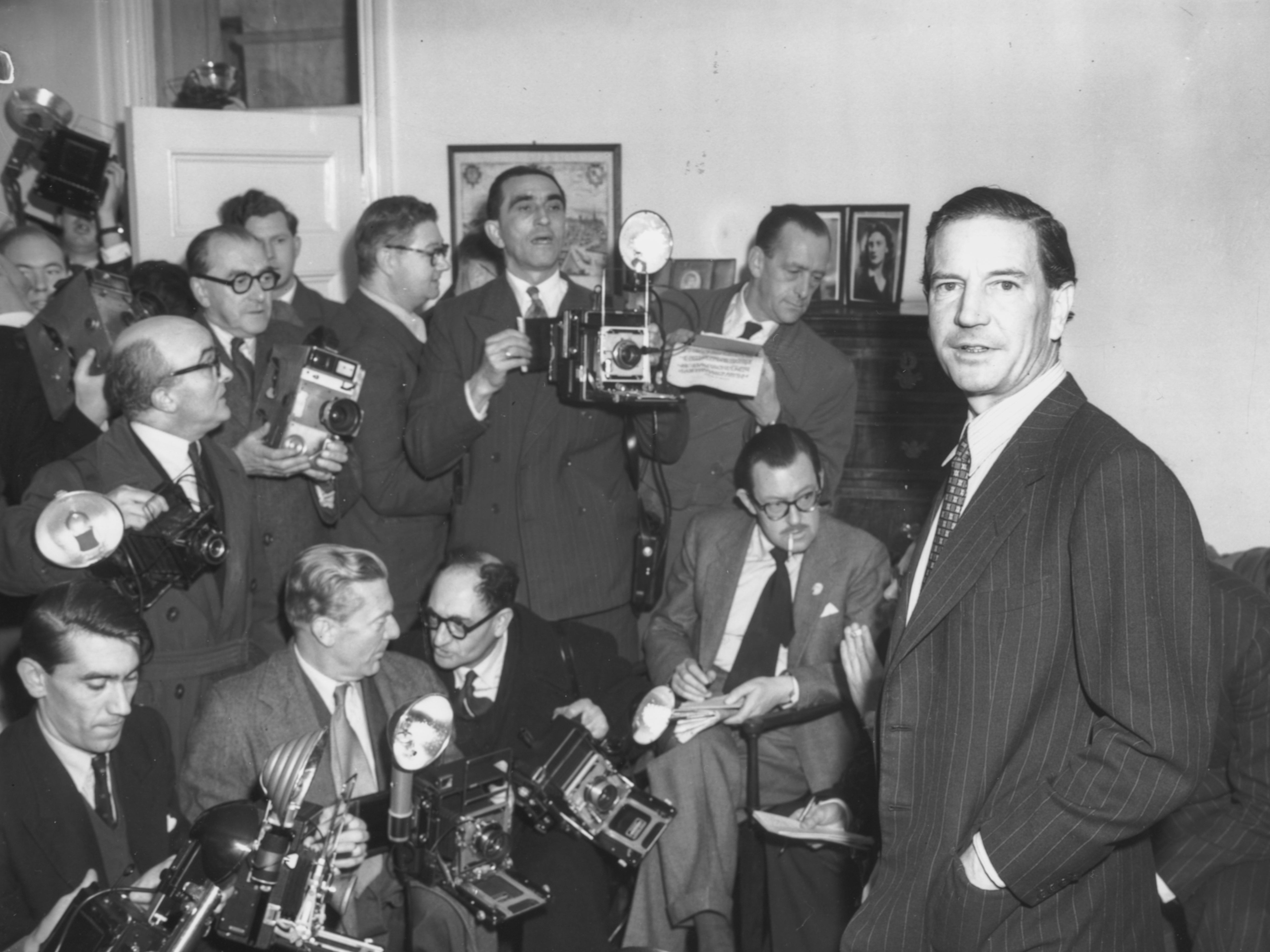

And so there lay the legacy of Philby and Blunt. Friendship, club and class loyalty overrode crimes against their own country. Philby’s smooth easy charm, camaraderie and charisma combined with his clubbable, disarming manner made him extremely effective as a double agent. For decades, his fellow MI6 officers simply could not believe that a gentleman from his background could have been a traitor, and they defended him almost to the end.

And even when Philby was exposed, confessed, and spent the final 25 years of his life as a lonely alcoholic in exile in Moscow, his establishment friends could not condemn him.

As Graham Greene, himself a former MI6 agent, wrote in the preface to Philby’s memoirs, My Silent War: “[Philby] betrayed his country. Yes, perhaps he did. But who among us has not committed treason to something or someone more important than a country? In Philby’s own eyes, he was working for a shape of things to come from which his country would benefit.”

This view that friendship overcomes patriotism was articulated in even more stark terms by EM Forster, who wrote: “If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.”

Philby and Blunt – arguably the most successful and effective double agents in espionage history – were fortunate to have such friends in high places. Philby lived out his final years in a comfortable if frustrating alcohol-dominated exile in Moscow, while Blunt, despite his betrayal, continued as an esteemed art historian for the monarchy until his death in 1983. If they had confessed and been convicted as Russian traitors in the Soviet Union, their fate would have been far more brutal: instant execution.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks