The London: After 350 years, the riddle of Britain's exploding fleet is finally solved

Exclusive: Archaeologists will recover a crucial item from the wreck which could help shed more light on what happened in the vessel's final seconds

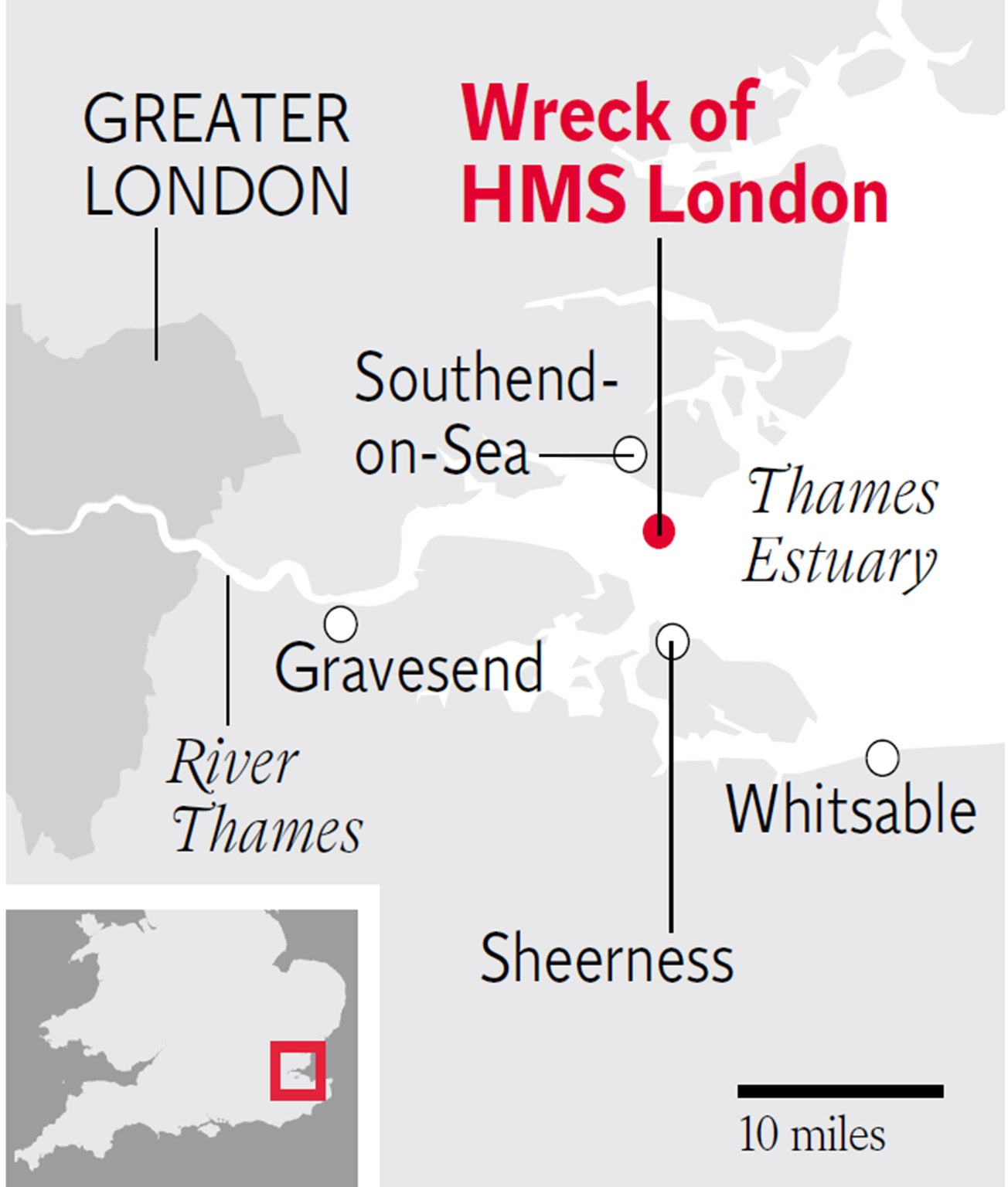

Bristling with cannon and packed with gunpowder, the English warship the London sailed through the Thames estuary in 1665 as she prepared to fight the Dutch in the English Channel. But she never made her destination, instead succumbing to a fate all too familiar in 17th century navies - "spontaneous combustion", explosion, and a watery grave for 300 of her crew.

Now, 350 years after the London's final voyage, archaeologists will recover a crucial item from the wreck which could help shed more light on what happened in the vessel's final seconds.

In the operation, scheduled for 12 August, divers plan to raise a perfectly preserved mid-17th century wooden gun carriage from the wreck of the London, which lies on the seabed about two miles off Southend-on-Sea, Essex. Complete with its wheels and axel, the gun carriage is the only known well-preserved English naval equipment of its type to have been found on a 17th century shipwreck.

"This underwater site is of great historic importance," said Charles Trollope, a weapons historian and fellow of the Society of Antiquaries who has been researching the London's fate. "English warship wrecks from the 17th century are extremely rare. It is the only surviving exemplar of the spontaneous explosion phenomenon which had affected the major navies of Europe up till that time."

According to Mr Trollope, it is likely that the London disaster was caused by the re-use of old artillery cartridges.

When re-used, some of the cotton in the cartridges deteriorated into a fine dust, some of which then combined with tiny quantities of sulphuric and nitric acids in gunpowder to form a highly explosive substance which much later became known as "guncotton".

That guncotton dust often came in contact with fresh gunpowder - and friction between the dust and the gunpowder sometimes led to massive explosions.

It is estimated that dozens of vessels worldwide self-destructed in the 16th and 17th centuries - causing deaths running into the thousands. The English suffered the loss of the Fairfax in the Medway, Kent, and the Sussex in Plymouth Sound, Devon, both in 1653.

Indeed, in England, it was the London disaster which finally forced the government to ban the re-use of old cartridges. The incidence of vessel self-destruction then reduced dramatically.

Mr Trollope - who studied explosives at Sandhurst - believes that an initial limited 'explosion' took place in the London’s forward magazine, where gunners would have been filling potentially dusty ‘high risk’ old cartridges with gunpowder.

This explosion would have ignited the roughly two tons of gunpowder in the magazine, and sent a much larger intense heat flash to the main store of more than ten tons of gunpowder kept in the vessel's hold. This larger quantity of gunpowder then exploded, tearing the vessel apart.

Archaeological work on the seabed shows that the London broke in half at exactly the location in the vessel where the ten tons of gunpowder would have been stored. Mr Trollope has even identified what the gunners were doing with the cannon themselves as the explosion occurred.

Of five cannon found around the wreck, three had been loaded with gunpowder cartridges and shot, and sealed with wooden plugs. One had not yet been loaded and a fifth was only half loaded and had not yet been sealed. He believes that the gunpowder store in the hold exploded as one of the gunners was halfway through loading that fifth cannon.

The massive blast propelled many of the cannon (and no doubt their gunners) out through the side of the ship for some distance. The vessel broke in two with much of the front half of the ship being propelled westwards by the blast. It finally came to rest on the seabed 400m away. At the same time the blast totally destroyed much of the central part of the vessel and forced the bottom of the ship downwards into the seabed.

The vessel's 'ship bottom' timbers have actually survived intact there - because they were shielded from the blast by a dense layer of more than 20 tons of disused old iron cannon, which were being used as ballast.

The Government’s archaeology and heritage protection service, Historic England, says that the gun carriage that has been discovered is “extremely rare”.

“It is the first time we have ever found a 17th century naval gun carriage on the seabed with all its equipment - including the pulley blocks and many of the gunners’ implements," said Historic England nautical archaeologist, Alison James.

The organisation has funded the recovery and study of hundreds of finds from the London wreck, which have mostly been brought to the surface by Southend-based volunteer divers acting on its behalf.

These finds include a small store of ‘spare’ leather shoes (15 pairs in total), hundreds of pieces of musket and pistol shot, dozens of galley tiles, a pile of galley firewood, a finger ring (complete with seal), a gun-loading rammer, four pulley blocks for gun carriages, a linstock (for igniting the charge which would have fired a cannon), a pocket sun-dial and the buttons from an officer’s tunic.

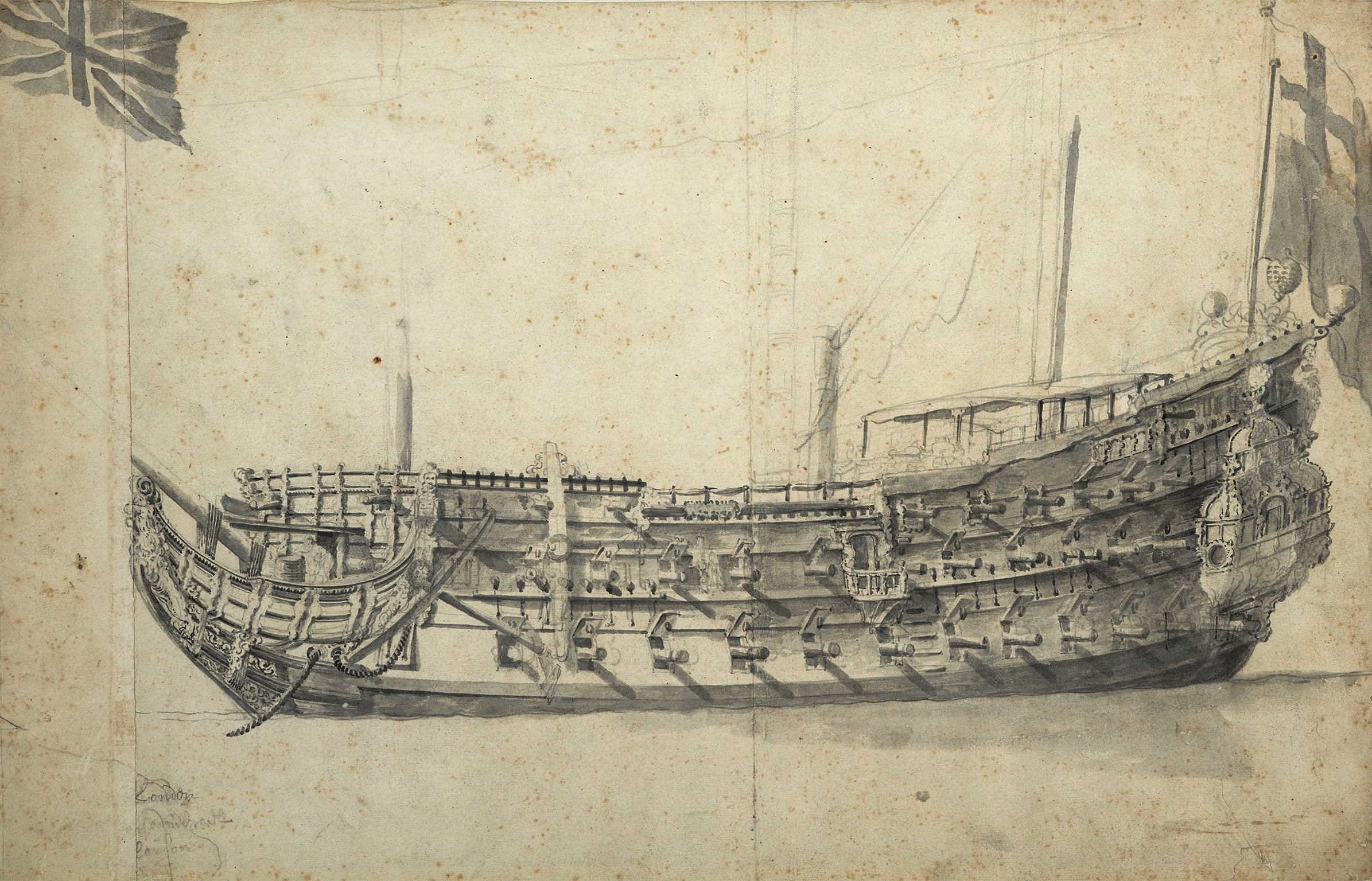

The London – armed with 76 guns – had been built in 1654-56 for Oliver Cromwell’s navy. In 1660 she was one of the small fleet of vessels which brought Charles II back to England at the Restoration. Prior to her explosive self-destruction in the Thames estuary in 1665, she had been one of the half dozen most important ships in the Royal Navy. Laden with cannon and gunpowder, she had been on her way to fight the Dutch at the beginning of the Second Anglo-Dutch war.

The raising of the vessel’s gun carriage next week will be carried out by divers assisted by a 20 tonne crane aboard a giant barge. It will be one of the largest marine archaeology rescue operations of the past 20 years.

The project is particularly important because of what it can reveal about England’s navy back in the 17th century - a particularly crucial era in its development.

But the nature of the London’s demise all those years ago will highlight the very serious threat that ‘spontaneous explosion’ posed to government navy, and indeed merchant, vessels and mariners of that era – a subject that has remarkably never been studied in detail.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks