Victorian juvenile criminals less likely to re-offend compared to modern counterparts, study shows

Around 73 per cent of young people re-offend within a year after release from custody now compared to 22 per cent in the Nineteenth Century

Victorian young offenders were less likely to go back to crime after being locked away than their modern counterparts, a new study shows. But before anyone rushes to reintroduce corporal punishment and gruel, the gap could be down to something much more benign: apprenticeships.

In the late Nineteenth century and early twentieth century, young offenders were typically put on a three year apprenticeship programme after being released from penal institutions. Now many are released with no formal help into the workplace.

A study of the lives of 500 children committed to reformatory or industrial schools more than a century ago has revealed that only 22 per cent re-offended during the rest of their lives after their release. Today, 73 per cent of young people re-offend within a year after release from custody.

Pamela Cox told the British Sociological Association’s annual conference in Glasgow yesterday (WED) that the low re-offending rate could be the impact of the supervised apprenticeship-type schemes that most young prisoners were put on for at least three years after release.

Professor Cox, of the University of Essex, is working with academics at the University of Liverpool and Leeds Beckett University to analyse the lives of offenders aged 7-14 from across Britain who were sentenced to institutions in Merseyside and Cheshire between 1870 and 1910. The research is the first historical analysis of re-offending rates for a large group of young people.

Professor Cox said: “We found that the rate of re-offending among the young people coming out of these institutions in Victorian and Edwardian times was dramatically less than it is today. This wasn't because it was harder to catch offenders in those days - we know from other studies that the re-offending rate among adults released from prison during Victorian times was 80 per cent, for example.

“In part at least it seems it is connected with the requirement that all those leaving the industrial and reformatory schools go into some kind of apprenticeship, or into the military. This set them up with a skill and gave them the routine of working that stood them in good stead in the future. Even among the 22 per cent or so who did reoffend, only 6 per cent were persistent criminals.”

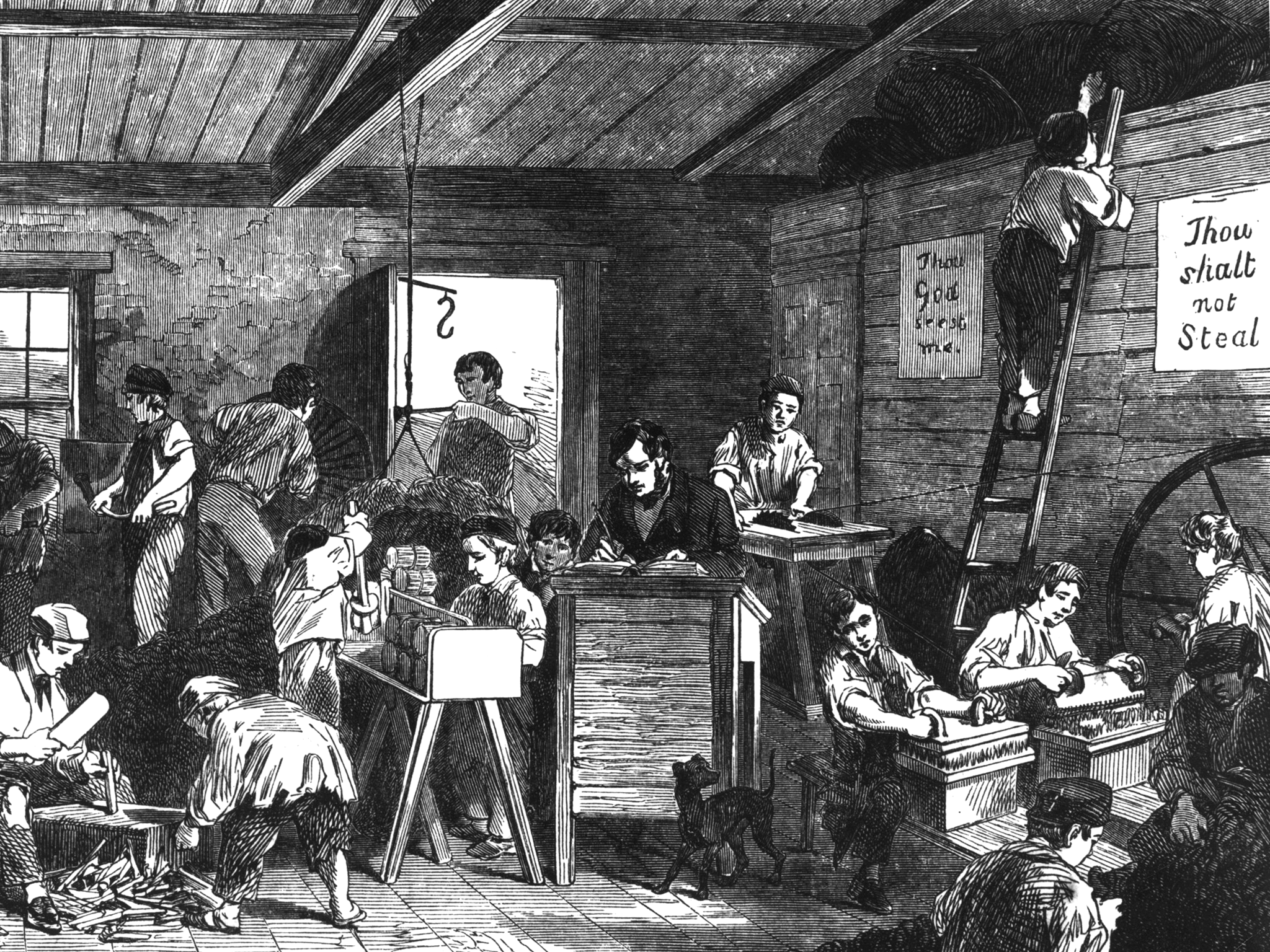

Most of the Victorian young people studied were teenage boys from poor backgrounds who had committed minor offences such as petty theft, vagrancy of public disorder. They were put into industrial and reformatory schools until 16 and upon release many went into apprenticeship schemes in trades such as shoemaking, railway work or in the military.

Juliet Lyon, director of the Prison Reform Trust, said: “Only 27 per cent of men and just 8 per cent of women are released from prison with a job or training place to go to. Of those young offenders who are selected as National Grid apprentices just 7 per cent are re-convicted within two years of release compared to around 70 per cent of all young offenders. Clearly there is much to be said for giving a second chance and finding gainful employment for those few young people whose offending is so serious that prison is the only option.”

As well as the impact of apprenticeships, the lower rate of reoffending more than a century ago may also be attributable to the fact that the young people were typically being punished for less serious crimes.

Falls in reoffending rates undermine private probation service

Sixty five young adults and teenagers have died in prison in last four years

Young offenders get higher achievement rates than national average

The three year study is possible because records from the late Victorian and Edwardian era have recently been digitised, making it possible for the first time to chart the entire lives of those who passed through the juvenile reform system. The team traced court records, census forms and other information to see their work history, marriages and other life events.

Professor Cox said: “We still know very little about the practical workings or long-term impacts of the early English juvenile justice system but by using innovative digital methods we have reconstructed the lives, families and neighbourhoods of 500 young offenders.

“For the first time, we followed these children on their journey in and out of reform and though their adulthood and old age. To date, no-one has used historical evidence on this scale to assess the effectiveness of juvenile justice policy and practice.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks