Magna Carta: The competing forces that cry out for a constitutional convention

The old certainties have gone and the constitution is now in flux

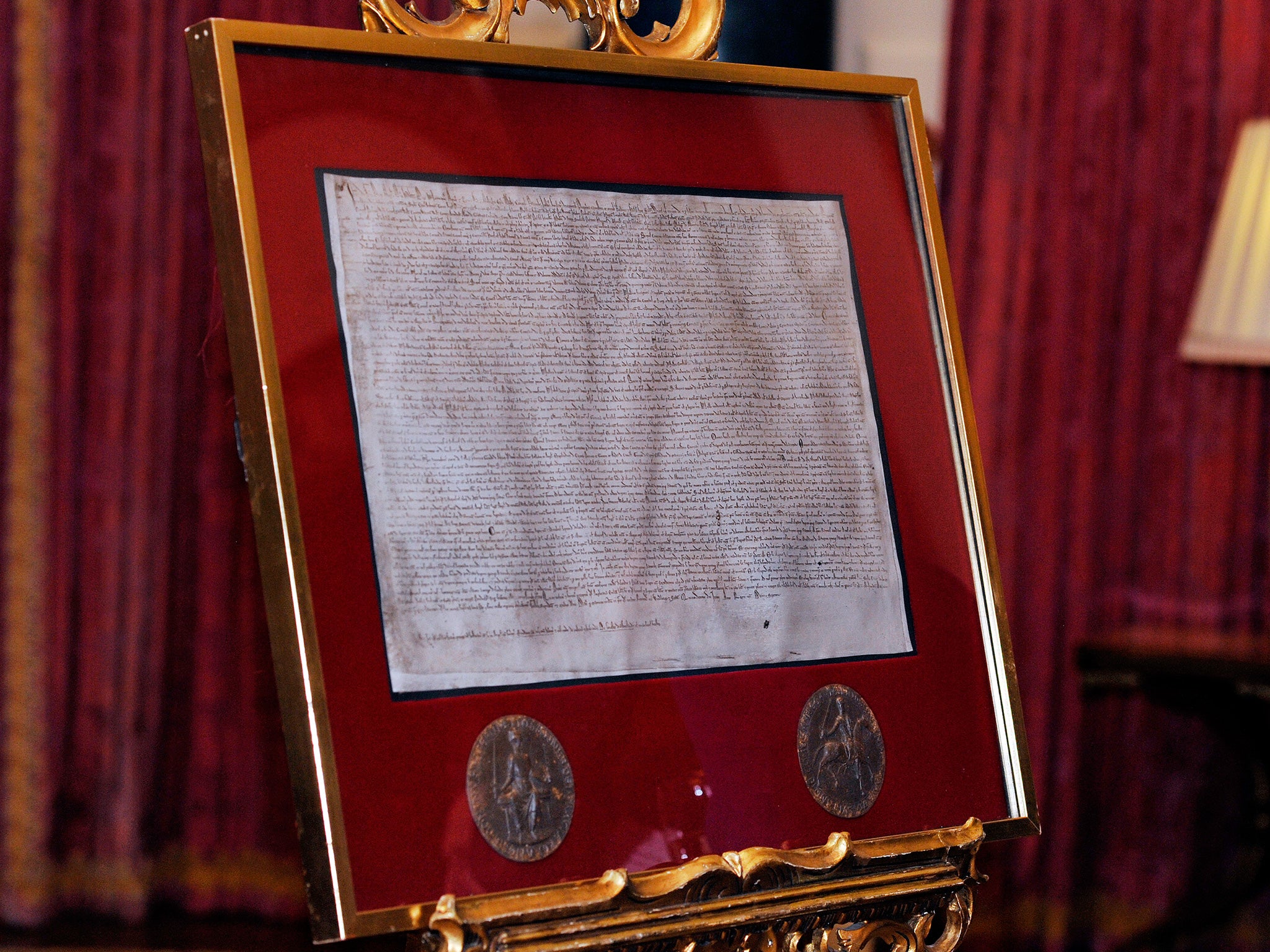

Eight hundred years after Magna Carta, which first gave us the idea that government rests on law, The Independent has been drawing together the threads of constitution as it is today, highlighting the supremacy of parliament, the Union with Scotland and our relationship with Europe.

On all these matters, however, there is great uncertainty. If parliament is supreme, what meaning can be attached to the rule of law? Can parliament override basic rights? Will the devolution to Scotland of further powers over taxation and welfare put the Union at risk? What, indeed, are the limits of devolution? Aneurin Bevan, it should be remembered, deliberately resisted separate Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish health services in 1946, insisting on a National Health Service. To do otherwise would offend against a basic principle of the welfare state, that benefits and burdens should depend not on geography but upon need. Is that principle now being compromised?

And finally there is Europe – the poisoned chalice for so many British governments since Harold Macmillan first sought to join the European Communities in 1961. If the European Union can pass legislation which has direct effect in Britain and which is superior to British law, what remains of the principle of the supremacy of parliament?

What the articles in The Independent show is that the old certainties have gone and that the constitution is now in flux. The Queen’s Speech at the end of May emphasised this by committing the Government to a whole plethora of reforms – not only devolution to Scotland, but also devolution to England, English Votes for English Laws at Westminster, repeal of the Human Rights Act and its replacement with a British Bill of Rights and Responsibilities, and a referendum on our continued membership of a reformed European Union.

The trouble is, however, that these issues are inter-dependent. The more power is given to the Scottish parliament, the greater the need to assuage resentment in England. Unionists have to secure a delicate balance between the needs of Holyrood and those of the English majority at Westminster. The Human Rights question and the European question both impinge upon the Scottish question as well as the Belfast Agreement, the basis of the constitutional settlement in Northern Ireland, which requires the consent of both communities – Unionist and Nationalist – to constitutional change. Can a British Bill of Rights be established without the consent of Scotland and Northern Ireland? If not, do we have to be content with an English Bill of Rights, and would that mean different standards for the protection of rights in different parts of the kingdom? Can Britain be taken out of the European Union without the consent of the Scots and of both communities in Northern Ireland?

Perhaps Britain is now a genuinely multinational state, a union of nations, each with its own identity and institutions, and each of which has a veto on matters of fundamental change. No one can be quite sure.

It is of course difficult for us to confront our constitutional problems when our parliament is so unrepresentative. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s party can no longer govern alone since it gained just 41 per cent of the vote. In Britain, David Cameron’s Conservatives can govern alone on 37 per cent of the vote. In Turkey, the Kurdish party with 13 per cent of the vote wins 79 seats. In Britain, Ukip, with a similar vote, wins just one seat.

This disproportion is of more than theoretical interest. In Scotland, the SNP swept the board, winning 56 of the 59 seats. An incautious observer might conclude that nearly every Scot supported separatism. But the SNP won just 50 per cent of the Scottish vote. The Unionists who also won 50 per cent of the Scottish vote are represented by just three MPs. First past the post makes Britain appear more divided than it is. Electoral reform would alter the dynamics of the conflict between England and Scotland, making it more manageable. There are of course considerable differences in voting behaviour between England and Scotland, as between the South of England and the North, but these differences are exaggerated by the electoral system, which now threatens the very unity of the country.

In 1997, the Welsh Secretary, Ron Davies, declared that Welsh devolution was a process, not an event. The same is true, surely, of constitutional reform as a whole. It is because our constitutional problems are interconnected that there is so strong a case for a constitutional convention. And one obvious matter to consider must be whether it is time for Britain to enact a constitution.

Britain, after all, remains one of just three democracies, together with New Zealand and Israel, without a codified constitution. It was said, over 100 years ago, that our constitution was based not on codified rules but on tacit understandings, and that “the understandings are not always understood”. How can we sensibly reform our constitution if we do not know what the rules are?

If one joined a tennis club, paid one’s subscription and asked to be shown the rules, one would not be pleased to be told that they had never been gathered together in one place but were to be found in past decisions of the club’s committee over many generations, lying scattered in many different documents, and that in any case some of the rules – conventions – were not written down at all. We would pick these up as we went along, with the implication that if we had to ask we did not really belong. Such a rationale might have been acceptable in the past when Britain was a more homogenous and deferential society. It will hardly do for the more assertive, multicultural country of today. Britain used to resemble a country house suitable for those prepared to live in it as guests and accept the rules of the proprietors. A codified constitution could help make Britain a genuine home for all of its citizens.

Countries tend to adopt a constitution when they have reached a constitutional moment, a break in their development such as a revolution or the attainment of independence. Britain has lacked such a constitutional moment since 1689 when the Bill of Rights, instead of providing a constitution, served to emphasise the principle of the sovereignty of parliament.

Perhaps now, 800 years after Magna Carta, we are approaching another constitutional moment, as we confront a series of interconnected and fundamental problems, all pressing for resolution.

The democratic spirit in Britain is not unhealthy. As the Scottish referendum showed, there is a huge reservoir of civic potential which has yet to be fully tapped. The task now is to channel that spirit into constructive channels. That indeed is the fundamental case for a constitution adapted to the modern age of participatory democracy.

Vernon Bogdanor is Professor of Government at King’s College, London. His books include ‘The New British Constitution’ (2009). His pamphlet ‘The Crisis of the Constitution’ was recently published by the Constitution Society

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks