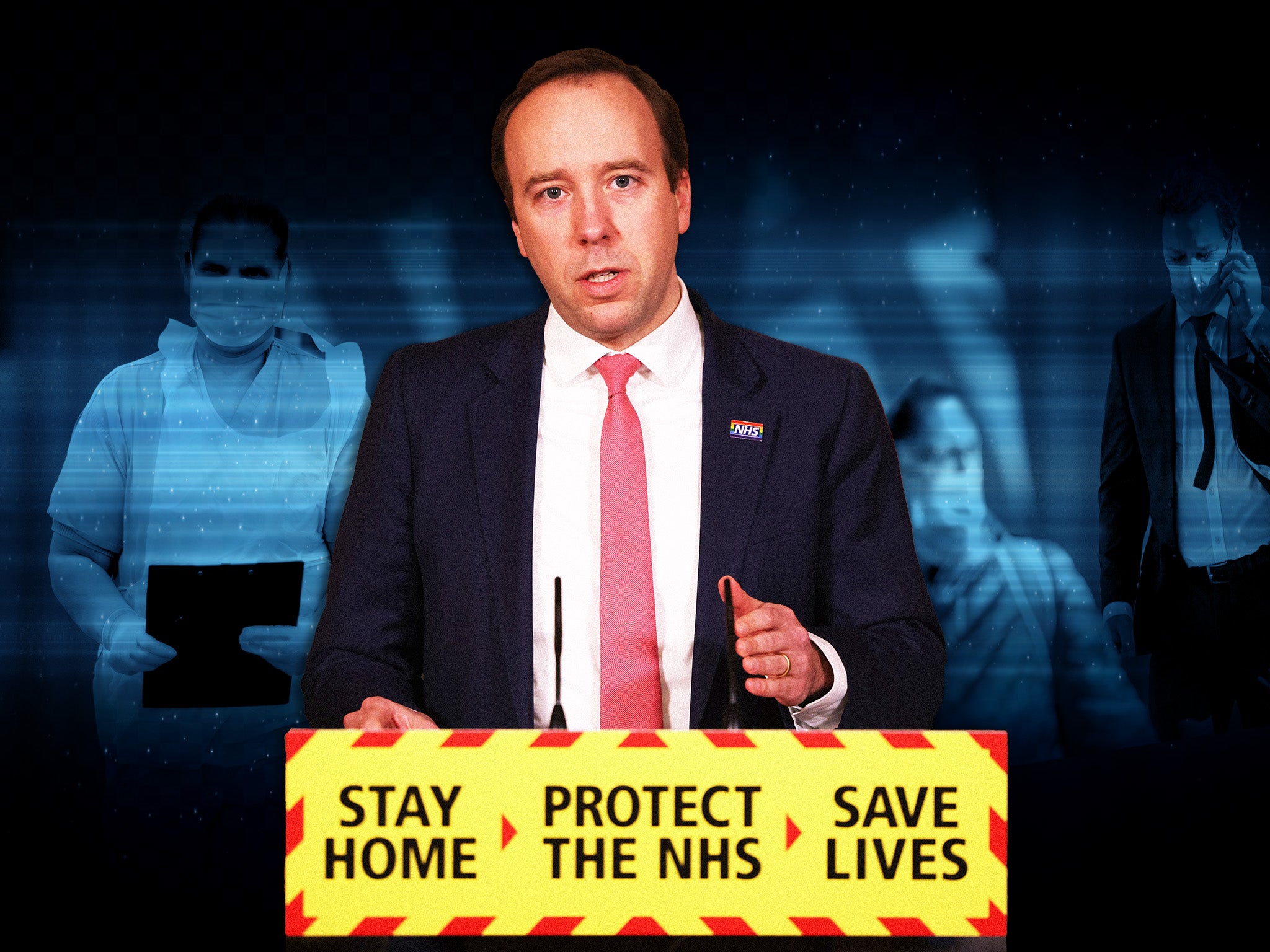

Matt Hancock seeks to humiliate himself in public again

After an astonishing rise, the fall of Matt Hancock from pandemic Health Secretary to floundering reality TV entrant somehow still fails to win sympathy from the British public. Funny that, writes John Rentoul

Matt Hancock must have felt that he had never been so exposed and uncomfortable as when the photo of his intimate embrace with Gina Coladangelo, his new lover, was all over the internet.

Yet he immediately sought further exposure and discomfort in pursuing a new career as a TV personality by going on a jungle-based reality show that involves eating camel penis and other forms of mild consensual torture.

Now he has put himself in for public humiliation a third time, throwing himself on the mercy of people who blame him for the deaths of their relations, and asking them to accept his explanations and apologies. He told the Covid-19 inquiry that he was “profoundly sorry for each death”, and that he understood why some people would find it “hard to take that apology from me”.

He went for the full personal confession: “I am not very good at talking about my emotions and how I feel, but that is honest and true.” The families who were at the inquiry and interviewed on TV afterwards didn’t accept his apology, but he seems to have calculated that nothing less than full contrition would do in appealing to wider public opinion.

You could say it is a brave approach, seeking absolution by further soul-baring, when people are not interested in the contents of his soul but in his management of a national emergency. In the inquiry witness box today he displayed all the strengths and weaknesses that have marked his career. The strengths are energy, hard work and a refusal to be cast down, but they are related to his weaknesses: a determination to want people to think the best of him even as he knows they won’t, and a willingness to trust a journalist – Isabel Oakeshott – who disagreed with him profoundly on ideological grounds with all his WhatsApp messages.

He was fluent on his subject and knew everything there was to know about how he did the job as health secretary. There were no evasions and “I can’t remembers”. Instead there was a willingness to accept that the country had been ill-prepared for a pandemic, and an even more striking willingness to take responsibility for that himself. Maybe that was a tactic to try to pre-empt criticism, but it had a strange effect: he seemed so sure that he had done the best he could in difficult circumstances that he was prepared to admit that his best simply hadn’t been good enough at times.

Matt Hancock is a highly developed modern type: the professional politician. He took the future politicians’ degree of choice at Oxford, PPE, philosophy, politics and economics, and became a special adviser. Not just any special adviser, but the special adviser to George Osborne, then the shadow chancellor. One of the most reliable routes to the top in politics is to make yourself indispensable to someone who is already en route to the top in politics.

I first came across Hancock as Osborne’s adviser, when Osborne was preparing for government. Hancock was quick, a good thinker about politics and plainly a useful adviser to his boss. Now, many years later, he reminds me of Peter Mandelson. Mandelson was a more important adviser, helping to create New Labour from the backroom, and he was more talented as a minister – he was actually loved by his civil servants, where Hancock was merely respected. But Mandelson was also unable to see himself as others saw him, and therefore unable to advise himself on how to deal with the scrapes that he got into.

Mandelson, like Hancock, and like Osborne, was brilliant at advising others how to deal with tricky politician situations, but they were all poor tacticians in their own cause.

Hancock was good at internal politics. He rose rapidly up the ministerial ranks, and continued to rise when Osborne, his sponsor, was cast into the outer darkness by Theresa May after the EU referendum (which Osborne advised Cameron against). He joined the cabinet as health secretary in 2018, when Boris Johnson resigned as foreign secretary and Jeremy Hunt was drafted in his place.

He survived Johnson’s return as prime minister, and his election victory, despite the hatred and contempt towards him (as a professional politician) felt by Dominic Cummings, Johnson’s chief adviser. That was political hand-to-hand combat at which Hancock excelled: he fought off Cummings’s attempts to get him sacked, not least by being conspicuously competent at a time when the centre of government was a shambles.

Hancock didn’t do a perfect job, as the Covid inquiry will no doubt find, but he stayed in what must have been one of the most difficult posts throughout almost the whole pandemic. By June 2021, the vaccine programme was well under way, and Cummings – who had left government at the end of the previous year – had tried and failed again, from the outside, to get rid not just of him, but of Johnson too.

Hancock must have thought he had survived the worst that the virus and his enemies could throw at him, when a huge story broke. The Sun had obtained a video from a security camera in Hancock’s office. It was a camera that neither Hancock nor his aides had ever noticed, installed when the office block on Victoria Street – never intended as a government building – had been built.

He had brought in Coladangelo, a friend from Oxford University, as a “non-executive director” at the Department of Health – in effect as an additional political adviser. They began an affair, and had been caught on camera failing to observe the guidelines at the time that required social distancing.

Hancock is about to appear in another reality TV show – the last one went so well: it got him slung out of the parliamentary Conservative Party, as the whips take a dim view of an MP heading off to Australia for weeks on end instead of working for their constituents at Westminster and voting when they are told to. And his time in the Australian jungle failed to endear him to the British TV-watching masses, failing to launch Hancock as the new Piers Morgan, which may have been his calculation. He came across as dogged, even-tempered and full of himself. Too late, he has already filmed SAS Who Dares Wins, in which he gets “put through hell”.

Once again, Hancock is preparing to humiliate himself by getting roughed up in public. And still the British people stubbornly refuse to feel any sympathy for him.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks