‘What are you hiding?’: Health officials stop reporting growing number of coronavirus cases at Nebraska meatpacking plants

Multiple cases and three reported deaths have been left unexplained

For weeks, people in rural communities in Nebraska charted the rise of coronavirus cases at the state’s several meatpacking plants. First, there were handfuls, and then, many more.

As of the first week of May, public health officials reported 96 at the Tyson plant in Madison; 237 at the JBS plant in Grand Island; and 123 arising from the Smithfield plant in Crete.

There were other cases around the state, too, and the counts were climbing. At least three were reportedly dead. Then the numbers stopped.

In a change initiated last week, governor Pete Ricketts, a Republican, announced at a news conference that state health officials would no longer share figures about how many workers have been infected at each plant. The big companies weren’t sharing numbers either, creating a silence that leaves workers, their families and the rest of the public blind to the severity of the crisis at each plant.

“What are you hiding?” said Vy Mai, whose grandfather died of the novel coronavirus after being exposed to her aunt and uncle, both employed by a Smithfield plant in Crete. “If the ‘essential’ workers are being treated fairly and protected at meatpacking plants, why aren’t we allowed to know the numbers?”

Around the United States, meatpacking plants have been associated with some of the worst outbreaks of the pandemic: of the 30 counties in the states with the highest per capita prevalence of the coronavirus last week, 10 are home to major meatpacking plants. Of those 30 counties, four are in Nebraska.

Mr Ricketts has said the numbers can be unreliable because some people who have tested positive have given misleading information about where they work. He recommended that local health departments withhold the case counts unless they get permission from the plants.

The company officials declined to share numbers, citing privacy concerns and the fast-moving nature of the virus. They note that they are implementing worker protections at their plants.

But workers and advocates say that without knowing how many infections have occurred at a plant, it is impossible to know how effective any such precautions have been.

“Governor Ricketts is taking steps to conceal testing results from the communities and workers that need it the most – this is a wrong decision at the wrong time,” Mark Lauritsen of the United Food and Commercial Workers, which represents many meat plants, said in a statement. “Workers, communities and companies all deserve this information so that we can make these essential workers as safe as possible. Transparency and honesty builds trust, ensures safety and keeps the food system functioning.”

Mr Ricketts said last week that 1,005 workers at meatpacking plants have tested positive for the virus, but he said that numbers from individual plants would not be announced.

“We do have aggregate data that we are tracking at the state, but that’s the only way we’re going to present it – as the aggregate,” Mr Ricketts said. “We have had people who are not telling the truth with regard to their place of employment.”

However, union officials said the case counts are surely rising because several large meat plants around the country, including two in Nebraska, are still in the process of testing their workers.

One of the biggest outbreaks, for example, may be at the Tyson plant in Dakota City, Nebraska. Neither the state nor local public health officials nor Tyson would say how many workers at the plant, which employs more than 4,000, have tested positive. But a person familiar with its operations who spoke on the condition of anonymity because they were not authorised to speak for the plant said the company was aware of 669 coronavirus cases there.

The Sioux City Journal reported the same figure for the plant, which closed for six days and reopened on Thursday.

“Since this is an ever-changing situation we cannot provide specific numbers,” Morgan Watchous, a company spokeswoman, said via email.

The company has two other large plants in the state: one in Lexington, where officials have yet to issue a report, and another in Madison, where on 30 April, public health officials reported there had been 96 infections, before the public counting stopped.

The officials at the Elkhorn Logan Valley Public Health Department, which covers the area, reported on 5 May that it hoped to update the figure. Then last week, the agency said Mr Ricketts’ decision meant it would no longer reveal how many cases there are at the plant.

“We are disappointed to announce that our office was just notified of this news story,” the agency’s website said last week. “We had been awaiting clarification on these statements from governor Ricketts. Until clarification is received, we will not be releasing Tyson information until further notice, or until we hear otherwise that we may do so.”

Shortly after this story was published, Tyson and the Elkhorn Logan Valley agency announced the results of testing at the company’s plant in Madison. Of the employees and contractors who work there, 212 tested positive for the coronavirus. The company said it would also release the results of testing at its other plants to employees, government officials and other stakeholders.

There were also counts issued initially for the Smithfield plant in Crete and the JBS plant in Grand Island.

Public health officials in those districts did not respond to requests for information, and the companies said they wouldn’t say either.

“Out of respect for our employees’ legal privacy, we will not confirm Covid-19 cases in our facilities,” according to a statement from Smithfield.

JBS officials did not respond to requests for comment.

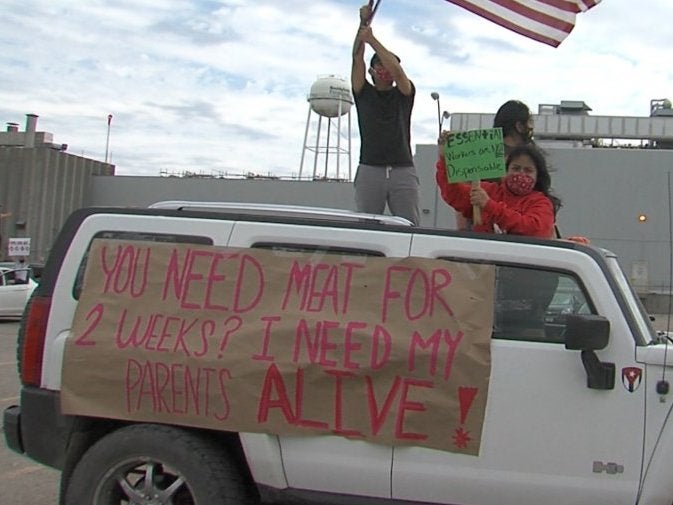

The absence of information has led to anger among some families of the workers. In many families, the first generation are workers who are afraid to speak out for fear of losing their jobs. Their children have staged protests.

Workers said they were outraged because the only standard for going back to work was to lack symptoms – people without symptoms can spread the virus.

“I’m afraid of catching it,” an immigrant who works at the Tyson plant in Dakota City said by text, discussing the matter on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing her job. “I have been at home for 21 days in quarantine but on Tuesday I’m supposed go back to work.”

She ended with an emoji of a scared dog.

The Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies