Ethan Couch: Why people might be too quick to dismiss 'affluenza'

A whole body of outraged commentary, biting satire and ridicule has grown up around that word

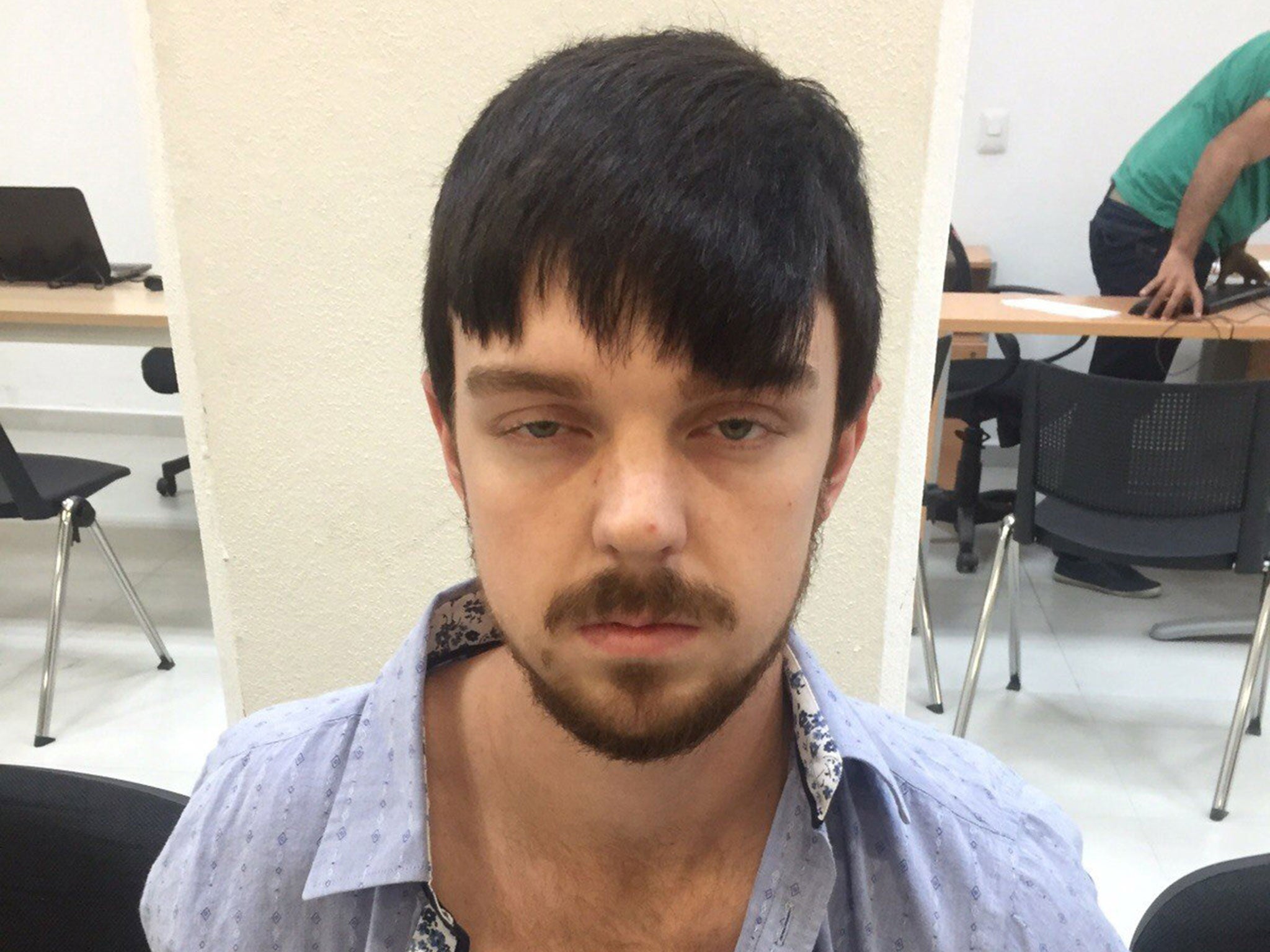

Ethan Couch’s crime was horrendous. He admitted to hurtling drunkenly at 70 mph along a suburban street in Texas on June 15, 2013, crashing into a group of people trying to deal with a disabled vehicle, taking the lives of four people and seriously injuring two others.

But it rose to national attention not because of that or because a judge in Tarrant County gave him only probation after he admitted his crime; it made national news and provoked howls of outrage because the judge did it after hearing a rich kid’s psychologist say the 16-year-old suffered from “affluenza.”

For the media and others, it was “a Petri dish of everything that’s wrong with the criminal justice system … the difference between wealth and poverty” and the use of “junk science” in the courts,” as CNN’s legal analyst Jeffrey Toobin said at the time. “There is no such thing as affluenza,” Toobin said.

A whole body of outraged commentary, biting satire and ridicule has since grown up around that word, “affluenza,” and all of it resurfaced last month after Couch and his mother took off for Mexico, only to be captured by Mexican police.

As a legal or psychiatric term, “affluenza” has no standing.

But submerged in the publicity surrounding the case, then and now, is a truth: Wealth can be damaging to the mental health of children. People sort of knew that: anecdotes from fancy schools of suicides, binge drinking, cutting, and sick examples of brutal hazing and sexual assault.

But there’s a growing body of research that “sometimes poor little rich kids really are poor little rich kids.”

That was the headline on an opinion piece published via Reuters this week by two psychologists, Suniya S. Luthar, professor of psychology at Arizona State University and Barry Schwartz of Swarthmore College. Couch’s affluenza defense has been ridiculed, with some justification:

That said, it would be foolish to allow an absurd effort to minimize one teenager’s responsibility for a horrific tragedy to obscure growing evidence that we have a significant and growing crisis on our hands. The children of the affluent are becoming increasingly troubled, reckless, and self-destructive. Perhaps we needn’t feel sorry for these “poor little rich kids.” But if we don’t do something about their problems, they will become everyone’s problems. …

… High-risk behavior, including extreme substance abuse and promiscuous sex, is growing fast among young people from communities dominated by white-collar, well-educated parents. …

… Studies show that drug and alcohol use is higher among affluent teens than their inner-city counterparts. And surveys have revealed that full-time college students are two and a half times more likely to experience substance abuse or dependence than members of the general population. Half of all full-time college students reported binge drinking and abuse of illegal or prescription drugs.

Then this: Serious depression or anxiety among affluent kids is “is two to three times national rates.”

Luthar said in an interview with The Washington Post that she understands that it may be a “laughable concept in the minds of many” to think of affluence as a source of potential malady. Indeed, she said, she was “taken aback” by her own findings when she first started research comparing inner city kids with suburban kids. “But I replicated it over and over again, and the finding was not going away.”

To see an example of the kind of research she’s talking about, read the paper she co-authored, “‘I can, therefore I must': Fragility in the upper-middle classes” or the book “The Price of Privilege: How Parental Pressure and Material Advantage Are Creating a Generation of Disconnected and Unhappy Kids,” by psychologist Madeline Levine.

In “The Price of Privilege,” to which Luthar contributed, Levine writes of her own therapy sessions with affluent teens and what she has learned from them.

“While they are aware that they lead lives of privilege,” she writes, “they take little pleasure from their fortunate circumstances. … Scratch the surface, and many of them are, in fact, depressed, anxious and angry,” with many engaging in “self-injurious behaviors like cutting, illegal drug use, or bulimia.”

She adds: “It is tempting to trivialize the problems of kids who have been the recipients of exhaustive parental intervention and have been liberally handed both material and educational opportunities.” But “regardless of how successful these kids look on the surface, regardless of the clothes they wear, the cars they drive, the grades they get, or the teams they star on, they are not navigating adolescence successfully at all …. Indulged, coddled, pressured, and micromanaged on the outside, my young patients appeared to be inadvertently deprived of the opportunity to develop an inside.”

To be clear, no scholar, including Luthar, is trying to defend the fact that a judge chose probation over confinement for Ethan Couch. Neither, for that matter, is the judge who made the decision, who has said nothing publicly since.

It’s not even clear that Tarrant County District Judge Jean Boyd, who has since retired, took seriously the testimony of the Couch’s hired psychologist, G. Dick Miller, who by his account, used the term “affluenza” almost as a throwaway line, he later claimed, as he described “a condition fostered by wealthy and permissive parents who encourage their children to believe normal rules do not apply to the affluent.”

‘This kid had medical problems,” Miller said in a later interview with WFAA in Texas. “He had social anxiety disorder. He had all sorts of things. He had depression. He found alcohol was his medicine. … I think that term, ‘affluenza,’ which I was just using to describe what we used to call ‘spoiled brats’ … it’s not a diagnosis. The diagnosis was something completely different.”

All the judge said at the time, according to news reports, was that she believed Couch would be better off in a rehabilitation center, a very expensive one, suggested by his attorneys.

“Boyd,” the Forth Worth Star-Telegram reported at the time, “said that she is familiar with programs available in the Texas juvenile justice system and is aware that he might not get the kind of intensive therapy in a state-run program that he could receive at the California facility suggested by his attorneys …. She also informed him that if he violated probation conditions, the probation could be revoked and he might serve as long as 10 years in prison. Among other strictures, the probation conditions forbid Ethan from driving. They also forbid him from drinking alcohol.”

World news in pictures

Show all 50It was that last restriction that appears to have gotten Couch into trouble in December, after a video was posted on Twitter showing someone who looked very much like him, by someone who indeed identified him as “ethan couch violating probation,” playing beer pong. A judge then ordered him detained, but it was already too late, as he and his mother had apparently disappeared. Both have since been captured in Mexico.

In the most thorough article to date about the Couch case, his parents, Fred and Tonya (now divorced), were described in the D Magazine headline as “The Worst Parents Ever,” in part for letting Ethan get away with such things as driving to school at age 13. “Court documents stretching back more than a decade tell the disturbing story of how, with the perfect combination of indulgence, addiction, abuse, and neglect, they created a nightmare,” said the article in May by Michael J. Mooney, about which the parents declined comment.

But substance abuse and drinking aren’t the only documented disturbances afflicting affluent teens. Suicide, by kids under pressure to succeed, is another, as powerfully described by Atlantic writer Hanna Rosin in her searing profile of suicide clusters at Silicon Valley high schools, including one called Gunn, between 2009 and 2010.

“Almost by definition,” Rosin wrote, quoting experts, “suicide points to underlying psychological vulnerability. The thinking behind it is often obsessive and then impulsive; a kid can be ruminating about the train for a long time and then one night something ordinary — a botched quiz, a breakup — leads him or her to the tracks. And of course, one thing that puts a kid at risk is someone else’s suicide. At Gunn, the scariest thing kids told me is that now, in one student’s phrasing, ‘suicide is one of the options.’”

But what of the term “affluenza”? It’s pop sociology, or pop psychology, that’s been used to describe everything from teenage depression to overconsumption contributing to climate change.

It has produced several books, a PBS documentary called “Affluenza” and even a woman who purports to provide treatment for it. Jessie H. O’Neill, author of “The Golden Ghetto: The Psychology of Affluence” defines affluenza as “a harmful or unbalanced relationship with money or its pursuits” that reflects itself in the individual in “addictions, character flaws, psychological wounds, neurosis and behavioral disorders caused or exacerbated by the presence of or desire for wealth.” She offers “phone and in-person counseling and consultations to individuals, couples and groups.”

“Affluenza,” though, has yet to make an appearance in the bible of ailments recognized by mental health professionals, The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

But in some news accounts, there’s a misunderstanding of the circumstances in which the term was used. It was not deployed as a defense to the offenses committed by Couch, four counts of intoxication manslaughter and two counts of intoxication assault causing serious bodily injury. Couch pleaded guilty.

“Affluenza” showed up as his attorneys attempted to persuade the judge not to follow recommendations by prosecutors in the juvenile proceeding that he be put away for 20 years.

It was an attempt at mitigation, which Los Angeles lawyer and legal scholar Lawrence Taylor describes in his treatise “Drunk Driving Defense” as offering “circumstances that tend to lessen the apparent badness of the particular crime or the apparent badness of the defendant.” The most common examples include the absence of prior offenses, the accused’s “extreme youth” or sometimes low IQ, remorse and apology and the potential for rehabilitation.

Affluenza is a new one.

In juvenile court, there’s “a lot more latitude,” Taylor said in an interview with The Post, because “the focus is on the well-being of the juvenile.” That, however, doesn’t make “affluenza” an acceptable argument, he said.

“Was it inappropriate” for Couch’s attorney to try a line of argument built around Couch’s affluence? No, Taylor said.

“But it’s pretty far out there. I would not do it because I think it would destroy my credibility as an advocate. Whatever else you have to say is going to be tainted by the notion that affluence is a defense.

“Like most people,” he said, “it’s difficult to have anything other than a sense of outrage” at the outcome of Couch’s proceeding. If the judge “thought the kid was morally deficient, why didn’t she keep him in custody for four or five years for treatment to correct the problem, rather than let him walk out with the same problem,” allowing it to “repeat itself” in some form, “such as taking off for Mexico.”

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies