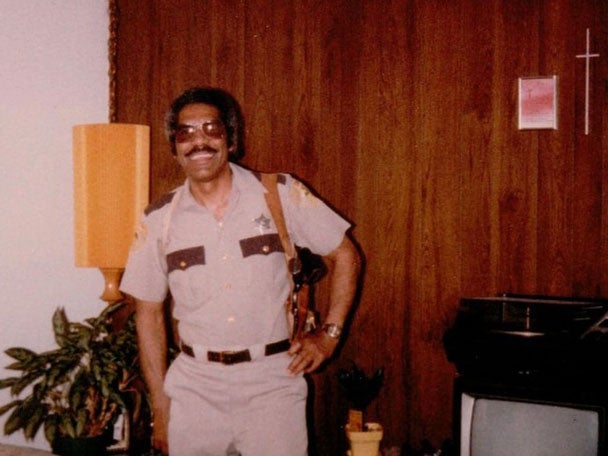

Lonnae O’Neal: What my dad’s suicide on Father’s Day taught me about life

The date snuck up on me as it always does. But this year, when I started hearing about Father’s Day sales and deserving-dad stories, I paid closer attention to how they made me feel.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of my father’s suicide, on Father’s Day. It marks an opportunity for me to wonder where the time has gone, and how my soul got over it.

In 1985, I was at summer school between my freshman and sophomore years of college when I got a call, I don’t remember from whom, saying there’d been an accident and I should come right away. I called my grandmother, who told me my father had shot himself. By the time I got home, he was dead.

Truthfully, I do very little looking back on those days. I’ve lived far more of my life without my father than I ever did with him, and there’s not a lot of cloth to my memories. And there’s this: When your daddy ends up killing himself, then obviously he was unavailable in all sorts of ways before he died.

It is largely that unavailability that the fatherless among us try to come to terms with for most of our lives.

For decades, people with father issues called into WHUR-FM’s Saturday morning relationship program “The Audrey Chapman Show.” “People make up fantasies about what a father is when they don’t have one,” says Chapman, a practicing psychologist. They idealize men on television. “That’s why Cosby was so important to people.” And transfer that idealization to the men in their lives.

Chapman says a father’s death by natural causes can be dealt with more concretely than if a child feels a father just left. Or “he can be in the home, but if he’s an alcoholic, drug addict or workaholic, then you have an unavailable parent and you still feel abandoned.”

You carry that with you in every relationship, says Chapman. You end up being somebody who leaves too soon, stays too long or puts up with too much, because you’re afraid you’ll get left.

In last month’s remarks at the “Conversation on Poverty” at Georgetown University, President Obama, who has written about growing up without his father, said he often talks to young men about the issue. “It’s true that if I’m giving a commencement at Morehouse that I will have a conversation with young black men about taking responsibility as fathers that I probably will not have with the women of Barnard. And I make no apologies for that,” he said.

“And the reason is, is because I am a black man who grew up without a father and I know the cost that I paid for that. And I also know that I have the capacity to break that cycle, and as a consequence, I think my daughters are better off.”

He said that at an event for his My Brother’s Keeper initiative, a boy asked him: “How did you get over being mad at your dad? . . . I’ve never seen him because he’s trying to avoid $83,000 in child-support payments, and I want to love my dad, but I don’t know how to do that.”

Obama told him how he “tried to understand what it is that my father had gone through, and how issues that were very specific to him created his difficulties in his relationships and his children so that I might be able to forgive him.”

Washington writer Jonetta Rose Barras heads a nonprofit group devoted to women’s fatherlessness issues. “Everybody sees mothers as really crucial to your development, but fathers are equally crucial, if not more so as you grow up,” she says. (This year, we’ll spend $13 billion on Father’s Day vs. $21 billion for Mother’s Day.)

Society is still male-dominated, she says, and fathers help translate the world.

In 2000, Barras wrote a book on her fatherless years called “Whatever Happened to Daddy’s Little Girl.” At readings, she found it “mind-boggling” to see 60- and 70-year-old women crying.

Barras, whose father tried to get in touch with her for decades before she knew of him, says that although couples break up, children still need their dads. “I always tell women, I don’t care what kind of relationship you have with him, I have a right to have a relationship with my father.”

She likens fatherlessness to diabetes or high blood pressure: You never get over it, but you learn to manage.

That sounds about right.

It wasn’t so much my father’s death as his unavailability in life that left me knowing something vital about the lives of my children — that they have to have their dad. When my marriage ended, I moved only five minutes away from my ex-husband. I wanted my children to have something I can scarcely remember but sometimes long for still.

Especially on Father’s Day.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies